Explainer: Turkey-Libya maritime deal rattles East Mediterranean

By Luke Baker, Tuvan Gumrukcu and Michele Kambas

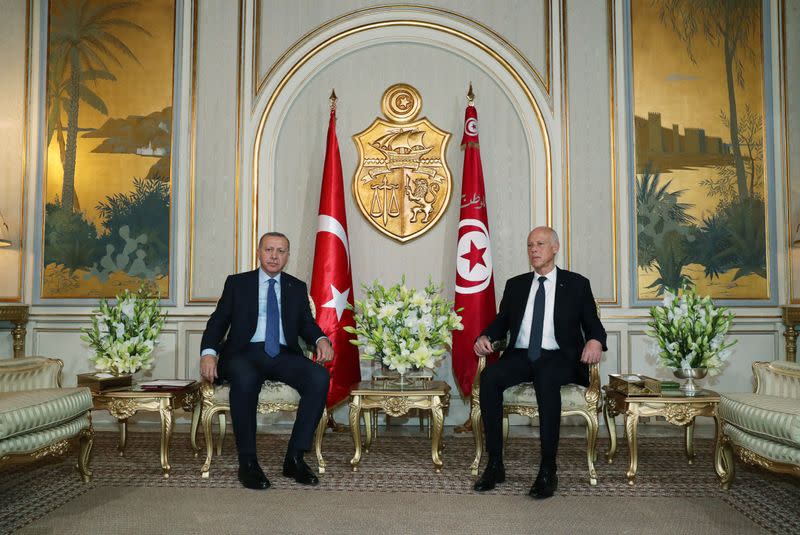

LONDON/ANKARA/ATHENS (Reuters) - Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan paid a surprise visit to Tunisia on Wednesday to discuss cooperation for a possible ceasefire in neighbouring Libya, where Ankara supports the internationally recognised government.

The visit comes after Turkey signed an accord with Libya's internationally recognised government last month that seeks to create an exclusive economic zone from Turkey's southern Mediterranean shore to Libya's northeast coast.

Ankara says the deal aims to protect its rights under international law, and that it is open to signing similar deals with other states on the basis of "fair sharing" of resources.

Greece and Cyprus, which have long had maritime and territorial disputes with Turkey, say the accord is void and violates the international law of the sea. They see it as a cynical resource-grab designed to scupper the development of East Mediterranean gas and destabilise rivals.

Greece has expelled Libya's ambassador to Athens and filed a complaint with the United Nations. Cyprus, where the northern part of the island is held by Turkey, has raised its own objections. At a Dec. 12 summit, EU leaders issued a statement "unequivocally" siding with member states Greece and Cyprus.

Egypt and Israel, which have invested heavily in energy exploration in the region, are alarmed by the Turkey-Libya move, which may threaten their ability to export gas to Europe. Egypt has called it "illegal and not binding", while Israel has said it could "jeopardise peace and stability in the area".

Following are some questions and answers looking at why Turkey and Libya struck their deal, the impact it could have on the region, and the shadow it casts over East Med gas.

WHAT'S THE MOTIVATION FOR TURKEY AND LIBYA?

Turkey has had disputes with Greece over islands in the Aegean for decades, and with the Republic of Cyprus over the island's maritime waters since 1974, when Turkish troops invaded the north after a brief Greek-Cypriot coup.

In striking the deal with Libya, analysts say Ankara has essentially put both Greece and Cyprus on immediate watch, showing it is prepared to act tough to get its way and/or force new negotiations over their long-standing disputes.

At the same time Turkey has thrown a spanner into the works of efforts by Cyprus, Greece, Israel and Egypt to develop East Mediterranean gas, putting a barrier across a proposed pipeline that would run from Israeli and Greek-Cypriot waters to the Greek island of Crete, on to the Greek mainland and into Europe's gas network via Italy. The $7-9 billion pipeline would have to cross the planned Turkey-Libya economic zone.

Analysts say Turkey has effectively sent a message that it will not be ignored in the East Mediterranean, isn't going to let EU members access what it sees as its maritime waters, and doesn't want energy exporters like Egypt and Israel gaining leverage over Turkey, a net energy importer and transit state.

For Libya, the motivation is mostly security. The accord was reached with Fayez al-Serraj, head of the Tripoli-based government, who is in conflict with a rival military force in eastern Libya under General Khalifa Haftar. Turkey has promised to step up military and other assistance to Serraj. Libya's eastern-based parliament, which is aligned with Haftar, has rejected the maritime accord.

WHAT DOES THE MOVE MEAN FOR EAST MEDITERRANEAN GAS?

The East Med basin is estimated to contain natural gas worth $700 billion, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. At one point it was regarded as a boon for the region, one that could deliver massive revenue, help forge a resolution to the Cyprus dispute and build closer ties between Israel and its neighbours.

But the key to unlocking the gas's value is exports and there's no easy way to do that. The proposed pipeline is costly and would run 3,000 metres deep in parts. The Turkey-Libya deal adds another obstacle to making it achievable. While there are precedents for pipelines crossing other countries' exclusive economic zones, Turkey won't make it easy. What's more, Ankara will use the deal to step up its claims to explore for energy in waters off Cyprus, where for months it has sent drilling ships, and in recent days flown exploration drones.

Analysts already had doubts about the viability of East Med gas because of the export difficulties and the price it would ultimately be delivered at, with Europe awash with cheaper gas from Russia and Qatar. The Turkey-Libya move only further complicates that difficult picture.

"In terms of geopolitics and East Mediterranean gas, this is a big deal," said Kadri Tastan, a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States. "Turkey is making a big move to try to force negotiations on a number of issues. It's going to be very hard to resolve."

WHAT ARE THE WIDER REPERCUSSIONS?

As well as putting Turkey on a collision course with Greece and Cyprus, it ratchets up tensions between Ankara and the EU, adding to ongoing disputes over migration policy and wider questions over Turkey's role in NATO.

It also raises the stakes with Egypt, which has been at odds with Turkey since the Egyptian military overthrew Islamist President Mohamed Mursi in 2013. Many of Mursi's Muslim Brotherhood backers now make their home in Turkey. In Libya, Egypt is more closely aligned with Haftar, meaning Cairo and Ankara are on opposite sides over the maritime deal.

Israel has been more circumspect over the Turkey-Libya move. One reason, analysts suggest, is that if the Israel-Cyprus-Greece-Italy pipeline becomes unviable, Israel may have to explore ways of exporting gas via Turkey instead. While Israel-Turkey relations have soured in recent years, trade remains strong and they regard each other as strategic partners. Israel will soon send some gas to Egypt to convert into Liquified Natural Gas for reexport, so relies less on Greece and Cyprus.

Russia is another piece in the puzzle. While it and Turkey are at odds over Syria, they coordinate on energy policy, and Moscow is keen for Turkey to transship energy. But the Turkey-Libya deal also puts them on opposite sides in Libya, where Russia leans towards Haftar. Russia and Turkey will discuss Libyan military support at a summit next month.

(Additional reporting by Dan Williams and Tova Cohen in Jerusalem, and Aidan Lewis in Cairo; Writing by Luke Baker; Editing by Gareth Jones)

Yahoo News

Yahoo News