Facebook struggles to stop false Covid claims from reaching millions of Indians online

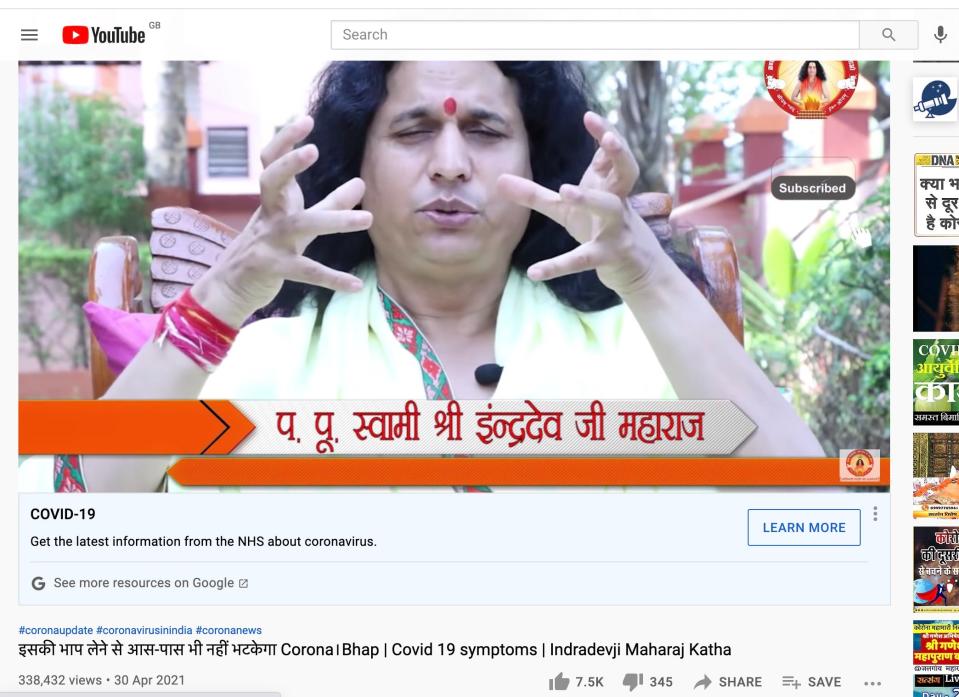

“If you take steam, there is no way you will get Covid,” Swami Indradevji Maharaj assures his audience in Hindi with the conviction of somebody explaining the obvious. “If the whole family takes this steam, there is no way coronavirus will come near you. Without a mask, without any sanitiser. It will sanitise your entire body from the inside. You get very strong, you get a lot of oxygen. Everything is cleaned out and your lungs are repaired. So, coronavirus can’t touch you if you use steam.”

The false claims in a video on Facebook are not new, and have been debunked repeatedly by fact checkers around the world since the early days of the pandemic. The World Health Organisation has warned of the dangers of steam inhalation since at least July last year, and there are numerous studies indicating it can cause severe burns, particularly in children.

And yet the video is just one example of a wave of dangerous misinformation targeting Indians on social media that these platforms are struggling to get to grips with.

For this report, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism identified more than 150 examples of misinformation in Hindi, India’s most widely spoken language, posted on Facebook pages and in public groups over 30 days in April and May. In total, the pages have an audience of more than 100 million people. Fewer than 10 of the posts were flagged as false information or had been removed by the beginning of June, and only 15 included a label pointing to more reliable information – one of Facebook’s most touted methods for mitigating the harm of false posts.

Facebook removed several of the posts after being contacted by the Bureau.

The problem is not unique to Facebook. An analysis of just a week on Twitter revealed more than 60 examples of misinformation shared by accounts with a combined reach of more than 3.5 million followers. More than two weeks after the tweets were collected, just five of the accounts had been suspended.

Twitter declined to comment, and directed the Bureau to a blog post from May on its efforts around Covid-19 in India.

Social media companies’ failure to deal with widespread, potentially dangerous misinformation comes at the height of India’s incredibly lethal second wave. More than 100,000 people died in India in May, making it by far the deadliest month of the pandemic there. Even these figures are thought to be a huge underestimate, with true fatalities as much as 10 times higher. Queues have formed outside cremation grounds with funeral pyres burning through the night. For two weeks in May, official deaths averaged more than 4,000 a day.

While social media businesses insist they take a strong stance against Covid-19 misinformation, the almost complete lack of flags on Hindi posts highlights the shortfall when it comes to some languages other than English – particularly those spoken by people in countries where Facebook and Twitter make less money from advertising.

Facebook’s average revenue per user in the Asia-Pacific region in the final quarter of 2020 was $4.05, less than a tenth of the $53.56 per user made in the US and Canada and a quarter of the $16.87 it makes from each European.

Pratik Sinha, the co-founder of fact-checking organisation Alt News, said the continued prevalence of debunked posts touting false cures and preventatives for Covid-19 is a result of what he sees as Facebook’s incompetence; “they are not held accountable,” he said. He added that while some automation was necessary to get a grip on the problem, Facebook and other tech companies need to invest in more staff to actively fight misinformation outside its most valuable markets.

That Facebook had not already done so, he said, was in his view down to profit margins. “The advertisement prices in India and the US are very different. You don’t make as much money per ad, so this is a pure business decision.”

Facebook employs at least 1,600 moderators in India via at least one contractor. However, moderators in non-English languages are frequently expected to be bilingual, and work on the English moderation queues as well as in their own language, according to private correspondence between moderators working in European hubs and Alex Hern, the Guardian’s UK technology editor. Moreover, while Hindi is spoken by 44 per cent of the population, it is just one of 22 official languages in India and, according to Facebook, its fact-checking partners work in only 11.

Facebook told the Bureau that ad revenue did not affect the size of its local moderation teams, and that it had thousands of moderators dealing with harmful content, including tackling Covid-19 misinformation in India. A spokesperson said: “India has one of our largest third party fact-checking programs, we partner with nine independent fact-checking organisations, including six who fact-check in Hindi.”

The data gathered by the Bureau from Facebook and Twitter provides a snapshot that likely vastly underestimates the scale of misinformation in India. Approximately 320 million people in India use Facebook, making it the company’s largest market, and its messaging platform WhatsApp is even more popular with recent reports suggesting it has almost 460 million users. WhatsApp is thought to be an even more dangerous source of and vector for misinformation, but as a peer-to-peer private network it is far harder for researchers to assess.

“In my understanding, that’s where it originates,” said Sumitra Badrinathan, an Oxford postdoctoral research fellow specialising in misinformation. “People, either with good or bad intentions, start to write WhatsApp messages, then it gets circulated around and then eventually hits the English-speaking population that then puts it up on Twitter and Facebook.”

YouTube is also known to be a source of misinformation. Swami Indradevji Maharaj’s dangerous and false claims about steam have been viewed more than 340,000 times on his verified YouTube channel, as well as being shared on Facebook.

With only 13 per cent of India’s population having received at least one dose of a vaccine, adequate healthcare too expensive for many and shortages of crucial medical supplies including oxygen, recommendations for false or unproven home remedies are common. As well as steam inhalation, dangerous recommendations such as putting drops of mustard oil or lemon juice in the nose, or drinking cow urine, are widespread on Facebook and Twitter.

Social media can also be a conduit for reliable information, often produced by fact checkers or medical professionals. Dr Harshwardhan Bora, a critical care consultant based in Nagpur, believes that among his metropolitan patients and contacts, social media has ultimately spread more facts and true stories than misinformation during India’s second wave.

But he has also seen several patients suffer adverse effects from herbal remedies being peddled as Covid-19 treatments by viral Facebook posts and text chains he wryly refers to as the “WhatsApp University”.

“In India, every household has their own herbal decoction preparations for immunity boosting purposes. They might contain different things. Turmeric, mustard oil, black pepper, neem leaves, curry leaves. Maybe some spices from the kitchen and herbs from the garden – [people] are using them as a decoction,” Bora said.

“[They then] face stomach upsets, nausea, and some exacerbation of the acid peptic disease.” He added: “And of course, if they’re drinking it too much, it can affect, in the long term, their kidney and liver functions.”

Facebook and Twitter’s failure to take action against false information in Hindi also raises questions about the companies’ relationship with the Indian government, which both courts and threatens them. Facebook in particular has faced widespread criticism for being seen to be unduly lenient on hate speech posted by members of the ruling BJP.

Twitter angered the government when it reversed a decision to block accounts tweeting about farmers’ protests near the capital at the request of authorities earlier this year. In late May, Delhi police showed up at Twitter’s local offices to announce they were investigating the company for labelling a BJP spokesperson’s tweet as containing manipulated media.

Further complicating the picture is India’s long history of Ayurvedic treatments, which are often pitched as a superior and more patriotic alternative to modern medicine. This has driven the sale of Ayurvedic formulations claiming to prevent and cure Covid-19. About 10,000 people turned up to the sale of an Ayurvedic “miracle cure” for the virus in Andhra Pradesh in mid-May, creating a “virtual stampede” according to the Times of India.

The combined influence of these two local factors for India’s pandemic misinformation are exemplified in Baba Ramdev, born Ram Kisan Yadav. The barefooted yogi in saffron robes is not the typical face of a billion-dollar corporation. But he has become an inescapable image; broadcast on television for daily morning and evening yoga routines, smiling down from billboards across India, selling a return to the ancient Hindu ways – via his products.

Ramdev’s medicine and consumer goods empire, Patanjali Ayurved, sells everything from food and cleaning products to Ayurvedic medicine from more than 47,000 retail counters and an online store. His combination of Hindu spirituality and big business has proved a good fit with India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, whom he endorsed on stage in 2014 before the BJP’s election win. At the inauguration of a Patanjali Research Institute in 2017, Modi declared: “Baba Ramdev will take Ayurveda, and inspire the world.”

Since June last year Ramdev has been touting “Coronil kits” as a cure for Covid-19. According to India Today, within four months Patanjali had sold about 2.5 million kits, making more than 2.5bn rupees ($34.2m) in revenue. A lab test carried out by Birmingham University found that the pills do not protect against Covid-19.

Although it has banned marketing Coronil as a cure, the Ministry of Ayush – a government department that has been criticised for its promotion of quackery, poor scientific research and badly tested pharmaceutical drugs – has certified Coronil as a “supporting measure” for coronavirus treatment. In February, Ramdev promoted the pill at an event featuring India’s health minister, Dr Harsh Vardhan.

Ramdev has repeatedly defended the pill and the claims made during its launch, saying it was given to 280 Covid patients in what he called a “clinical trial” and that all of them subsequently recovered. He said at the time that “there has been no wrongdoing” in the way the product was marketed.

Despite Facebook and Twitter’s policies on Covid-19 misinformation, Ramdev remains a hugely popular figure on social media, free to make false claims about his products, other traditional remedies and modern medicine.

Over the month-long period examined by the Bureau, Ramdev’s official and verified Facebook page, which has almost 12 million followers, released five videos containing false claims about the effectiveness of Coronil, other remedies and yoga in treating Covid-19, as well as denigrating modern treatments. In total the videos racked up more than three quarters of a million views.

He has also spread similar false claims on Twitter to his more than 2.4 million followers. One video on Twitter, in which he mocks Covid-19 patients for not being able to breathe properly, has been viewed almost 800,000 times.

None of these posts have been flagged by either company as containing false or misleading information, but Facebook removed all five videos after the Bureau presented them to the company.

At the start of June, thousands of Indian doctors wore black armbands and demanded that Ramdev be arrested for spreading misinformation. He recently claimed he did not need a Covid-19 vaccination because he does yoga and practises Ayurvedic medicine.

Ramdev apologised for calling modern medicine “stupid science” and said he withdrew that and other claims he made about it killing Covid patients. He had been asked to do so in an open letter from the health minister, who called his statements “deplorable”.

Badrinathan believes Ramdev’s continuing presence on Facebook is a “million dollar question”.

“I think it’s complicated by the fact that he is supported by a lot of people who have elected seats in government. We’ve seen reporting before from The Wall Street Journal about how previous attempts by Facebook to take off misinformation or otherwise generally label hate speech has been met by resistance from the government. So one of the answers might lie in that he’s not an independent Baba sitting somewhere, he is a very political figure.”

She added: “Obviously, the normative question is, why isn’t Facebook blocking him into oblivion on their site? But the more empirical question is, if they did that, what would happen? And I suspect other people who like him for their own political purposes are still going to share that kind of misinformation.”

Read More

Twitter helps India block account of singer Jazzy B who tweeted in support of farmers

Orchard owner arrested after two elephants looking for food electrocuted in India within two days

Yahoo News

Yahoo News