Fat White Family’s Lias Saoudi: ‘Lockdown was like rehab’

Lias Saoudi sits down in the pub, takes a sip of Guinness and immediately starts sucking on a vape. “I’ll have a fag if I’m out having a proper drink or if I’m having a bit of a party,” he says. “But it’s got to the point where I feel a bit grossed out by a cigarette.” That’s the first surprise. The lead singer of Fat White Family, one of the most debauched and exciting bands to emerge in the UK this century, is rarely without a cigarette on stage or in interviews.

The second surprise is his appearance. He is wearing a grey woollen rollneck, his hair tightly cropped, his face a little fuller than when I last saw him perform – topless, cheeks drawn, lank black hair down to his shoulders. He looks healthy and together now – a far cry from the increasingly emaciated, tortured figure who haunted the stage as the band he formed in 2011 with his brother Nathan and Saul Adamczewski slowly ripped itself apart, poisoned by drugs, alcohol and ego.

So what happened? Lockdown, basically. “It was sort of like rehab,” says Saoudi. “All that carry on, for me, is circumstantial and social. Once all that was gone, I had no hankering.”

He holed up at a friend’s flat in Streatham during the first months of Covid, where he rediscovered his love of reading and writing. He began jotting down memories and ideas, the first time since school he’d written anything other than lyrics. “It was just the most fulfilling thing. You’re just, like, excavating your own life,” he says. “It was the first time I’d been truly happy creatively since I was a teenager.”

Or at least that’s one part of the story. Saoudi later tells me that, during the second or third lockdown, he can’t remember which, he found himself in Ireland with another writer. “We were embroiled in this, not satanic ritual, but adjacent, and a kind of alcoholic abyss,” he says. “Then we all got Covid. It was just this completely nightmarish situation.”

Still, the vape represents something like progress, for it wasn’t long ago that heroin nearly put an end to Fat White Family. Founding members Nathan, Adamczewski and guitarist Adam Harmer had all developed serious addictions.

Adamczewski was thrown out in 2015 (he has since been welcomed back, is clean and recently became a father for the first time). In 2018, Harmer was ordered to leave the house in Sheffield where Fat White Family were recording their third album, Serf’s Up. “We can’t have you back in the house,” Lias told him at the time. “I’m sorry. Heroin just f***s everything up.” Harmer pitched a tent in the graveyard at the end of the road.

“It got dark once heroin started to get involved,” says Saoudi. “The river split at that point because you’re just on completely different psychic wavelengths. [Heroin] was never the one for me. I liked uppers and socialising and chasing girls around. I didn’t want to sit and watch Countdown.”

Well, that’s not quite true. “I did dabble a bit on the old Countdown,” Saoudi laughs. “It’s not a bad show, you know.”

He pauses. “It would be an insult to those guys to claim that I was a junkie. I guess by [the standards of] a normal person’s life I was definitely a junkie as well. But it happened much later. And it really was more sporadic. I can count the times I’ve gone to pick up heroin on the street, like, on two hands.”

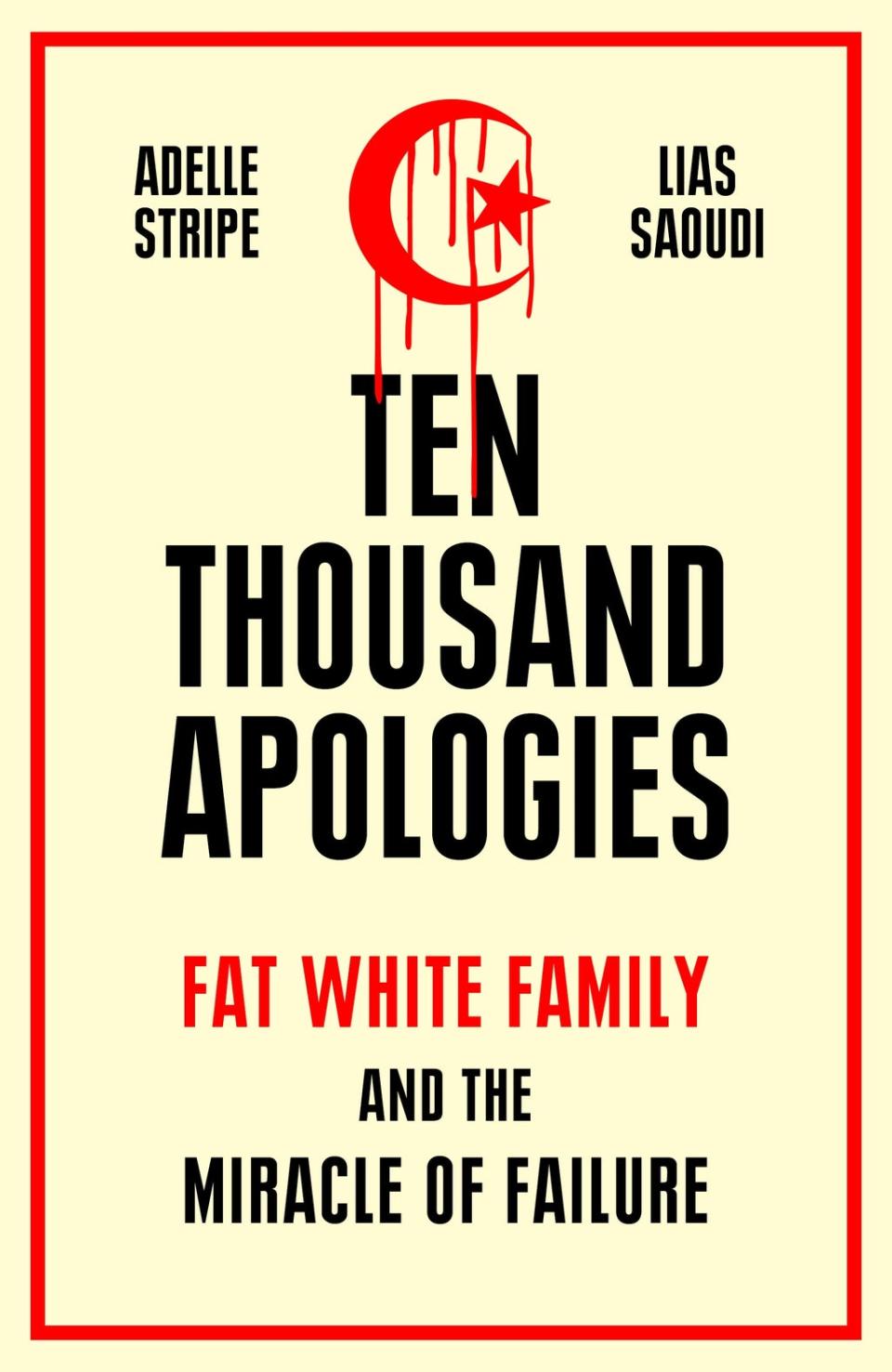

We’re in Brixton, south London, longtime home of Fat White Family, to talk about Ten Thousand Apologies: Fat White Family and the Miracle of Failure, a memoir of sorts by Saoudi and the journalist and novelist Adelle Stripe. It is a bruising, exhilarating read, which captures the nihilistic energy of this strange and brilliant band. It reminds me of Mark E Smith’s freewheeling, deranged memoir, Renegade.

Each page reveals fresh depravities and triumphs. There is infighting, substance abuse, the unlikely success of 2013 debut album Champagne Holocaust, squats, sackings, an appearance on The Late Show with David Letterman, songs called “Love is the Crack” and “Goodbye Goebbels”, rehab and, ultimately, with the release of Serf’s Up in 2019, something like redemption.

It must have been hard to pick at all those scabs again. “I think doing this was really helpful and cathartic,” says Saoudi. “Looking at it all written down and placing yourself within it, building a narrative out of it – it was like, man, that was f***ed up.” When I speak to Stripe the following day, she says she often “felt like Dr Melfi sitting with Tony Soprano. It was sort of a psychotherapy exercise, except I’m not remotely qualified to be doing that.”

Communication was always a problem for Fat White Family. But the process of writing Ten Thousand Apologies forced Saoudi, whom Stripe describes as “a mix of Harold Steptoe, Oscar Wilde and Adrian Mole”, to confront many of the conflicts and resentments he and his bandmates had avoided for years.

“We’re not good at talking about our emotions,” says Saoudi. “We’re the classic toxic men that everybody keeps talking about. Bang to rights. So that did create a very insidious atmosphere where the worst of everybody was getting propelled and inflamed over the course of years and there was just no get-out clause. Do the gig, get in the van, go to the studio, do the album – there was never any time for any kind of perspective. So it really did get kind of monstrous as a result. But having that long silence and emptiness of lockdown, going over it all and actually talking about things, I think it’s been pretty helpful.”

We’re the classic toxic men that everybody keeps talking about. Bang to rights

Lias Saodui

The book is not always kind to Saoudi’s bandmates, however. On the night of the terrorist attack at the Bataclan in Paris in November 2015, when Fat White Family were performing at another venue in the city, we are told that “Saul had commanded the rest of the band to stay in the dressing room, informing them, ‘It’s the safest place we can be. We shouldn’t go outside.’ But it turned out he didn’t say it because he genuinely cared for the safety of the band, he said it because he had arranged to meet his dealer. He was waiting for the man.”

What did the band make of the book? “It was quite painful for Saul to read it all back,” says Stripe. “That behaviour is tied to the darkest points of his addiction and Saul was very, very candid with me. He’s not proud of it but at the same time, you know, it was an incredibly bleak period for him. Anybody, regardless of who you are, if you are addicted to heroin and crack, and you are living in a crack house, you are not going to behave in a way that is palatable.” Saoudi, on the other hand, tells me that, “generally speaking, Saul was kind of like, ‘nah, it should be worse. It should be dirtier, it should be harsher.’”

It is hard to imagine how it could be. The book pulls no punches. Nor does Saoudi, who turns 36 next month but certainly hasn’t softened. I ask him for his opinion on the current political class. “People talk about a blue pill and a red pill,” he says. “The black pill is what I subscribe to at this point. Abject hopeless nihilism. What’s happening now has really disturbing shades of authoritarianism.” What about Keir Starmer? “If you’ve got a bod like Keir Starmer, who’s kind of like Tory in red clothing, then the powers that be might swing that way, like they did for Tony Blair. Why not? I certainly wouldn’t vote for him.”

Saoudi, the frontman who has masturbated on stage, written a song about Harold Shipman and once smeared himself with his own excrement during a gig (“The rest of the tour sold like hot cakes after that”), is still as provocative as ever. And he is appalled by what he describes as the “establishment of a state of self-surveillance”.

“People have this illusion that we live in a liberal democracy,” he says, “but that ran out of steam quite a while ago and the world we live in is something much more akin to the one I experienced in China 12 years ago, only here people seem faintly more invested in the delusion that it’s anything other than a controlled society.

“It was traditionally the right who were forever trying to get things banned and cancelled, so there is a creeping sense of political homelessness if you’re into avant-gardism in any way, shape or form and free expression for free expression’s sake. I definitely feel like I don’t have a tribe.”

So what did he make of Elvis Costello’s announcement that he would no longer perform his song “Oliver’s Army” because it features the n-word? “He’s at liberty to capitulate if he likes,” says Saoudi, who uses the word in Fat White Family song “Feet”. “What are you going to do? Put a blanket ban on a term? What if it is personal to you? Who’s to say what is and isn’t personal to someone?

“There are no real rules,” he continues. “They’re just transient and it either resonates or it doesn’t and the best you can do is completely ignore that hullabaloo. I mean, where would you draw the line? Are you going to take Caravaggio off the wall because he killed a bloke? I don’t understand where the line is. I prefer to draw no line.”

Saoudi has found his stride now, but he pauses briefly to finish his Guinness. “An artist has an ability to draw the line amid the chaos and mess of human experience and that’s the end of it,” he says, glass back down on the table. “It’s not a power that can actually be taken away from somebody. You have to give up on that yourself.”

'Ten Thousand Apologies: Fat White Family and the Miracle of Failure’ by Lias Saoudi and Adelle Stripe is out on Thursday 24 February, published by White Rabbit (£20)

Yahoo News

Yahoo News