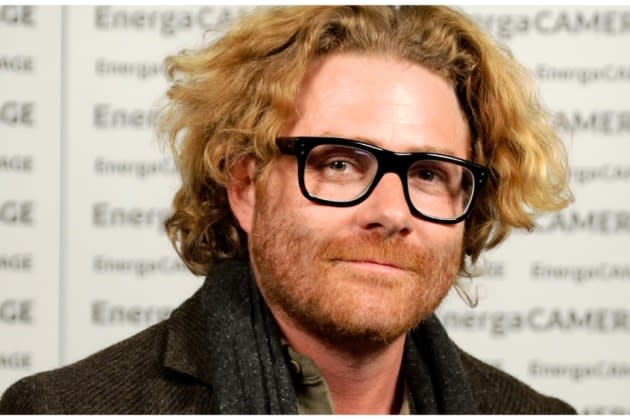

‘Ferrari’ Cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt on Capturing the ‘Visceral Nature of Auto Racing of That Period’

Michael Mann’s “three decades of research” provided the key to putting audiences in the driver’s seat of vintage Ferraris racing down a thousand miles of Italian roads that are well known for taking human lives.

That’s what “Ferrari” cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt discovered when he teamed with the director of crime classics such as “Heat” and TV’s “Miami Vice” to tell the story of Enzo Ferrari, founder of Italy’s most iconic racing car company, played by Adam Driver.

More from Variety

10 Key Takeaways From Camerimage Cinematography Film Festival

Cinematographer Robbie Ryan: Director Yorgos Lanthimos Worked Crafts Magic on 'Poor Things'

“I asked him what I should look at and Michael said, ‘Why don’t you start with my library.’”

Messerschmidt, himself known for exacting work on such films as “Citizen Kane” backstory “Mank,” which won him an Oscar, learned that Mann had indeed been researching Ferrari for 30 years. The director had accumulated hundreds of books, photos, newsreels, clippings and letters documenting every aspect of Ferrari’s life, the early days of auto racing, plus equally impressive holdings on crime, psychology and other subjects of interest.

“He had this amazing archive,” says the cinematographer. “So I started there.”

The material was more than enough to help Messerschmidt picture the sleek, fast and often deadly open-top racecars of the mid-1950s and the landscapes they flew down on races like the Mille Miglia – the thousand-mile cross-country race that determined whether someone like Ferrari would realize his dreams or go bankrupt.

“The race sequences use all real cars, real Italian roads, no green screen,” Messerschmidt says, with custom-built modern vehicles with vintage-style shells enhanced by something extra: “British engineers built-in mounting points for cameras. That was essential to Michael.”

Mann wanted audiences to “feel like they have to wipe the grease off their goggles,” says Messerschmidt. “So we wanted to avoid the classic coverage angles that you typically would do in a car movie. It’s a different grammar, almost.”

Indeed, eschewing any effects to make racers appear to be roaring down roads faster than they were really going, says the cinematographer, “Michael wanted the cars to go at the actual speeds – the cars are really going at competitive speeds.”

With cameras bolted to the frames of Ferrari mockups, he adds, “We could do it very safely and they were rigid. These particular cars are such a character in the film and it was very important to Michael that the audience experience the visceral nature of auto racing of that period.”

That encompassed the dangers too, says Messerschmidt, noting that racers of that era had no seatbelts – not because Ferrari hadn’t thought of driver safety but because getting thrown from a car was the driver’s best chance at surviving a crash.

“They catch fire,” the cinematographer says. “They’re amazing machines.”

Racing scenes aside, the specific light and tonal qualities of Northern Italy were carefully captured for other settings on location shoots, including home interiors and the spare, almost Spartan office of Ferrari, says Messerschmidt. At Mann’s suggestion, he studied Italian late Renaissance portrait paintings of Titian, Tintoretto and Caravaggio to get the look just right.

The paintings of that period, says Messerschmidt, “really speak to the way the interiors of Italian homes look. The lighting is very simple, they’re dark, there are shutters on the windows, there’s lots of window treatments. And we liked the idea of the Ferrari house being the darker, colder, more restrictive space and the Lardi house being the only place where he’s in the sun.”

Ferrari’s mistress, Lina Lardi (Shailene Woodley), bore him a son, Piero, whose legitimacy and title became a major crisis for the racing mogul, whose first son, Dino, had died the year before the story in the film begins, in 1957.

That relationship and the deeply troubled one with Ferrari’s wife and business partner, Laura (Penelope Cruz), are developed with nuance in “Ferrari,” each set in a home that reflects those distinctive Old Masters visual qualities.

Filming on the Sony Venice camera, Messerschmidt also went to Panavision and spoke to master optics guru Dan Sasaki about how to enhance the period look further, he said.

“We took a set of lenses that had been designed for me for the film ‘Devotion’ and we modified them slightly so there’s a little bit of spherical aberration in the lens that adds some softness in the highlights and cuts the contrasts slightly.”

For racing sequences, he explains, “There’s lots of long lens work in the movie, lots of zoom work. In the Ferrari house we’re on wide lenses and it’s more classical in its design. We’re wider and closer to all the actors. When we get to the races, on longer lenses and compressing the space – it’s a different esthetic.”

Messerschmidt, Mann and the team were also racing against the clock, says the cinematographer. “The whole movie was hard – we had a tight schedule, we were an independent film for a studio picture, with no second unit, so it was tight.”

“We shot all the – for lack of a better word – dramatic stuff first, the interpersonal relationships.”

Cruz, who shines in the grieving, pistol-packing wife role, had a short window of availability, says Messerschmidt, “so had to be done up front. I think that was a lot for Adam and the rest of the cast – they had to do the whole story arc in the first weeks of the movie.”

But the cinematographer was determined to make things work, whatever the time frame, he says. Having seen all Mann’s prep and passion, he explains, “I felt this enormous responsibility to deliver for him. He’s a legend. I’m a fan.”

Working with fewer resources than he has often had with director David Fincher, with whom Messerschmidt shot globe hopping thriller “The Killer” this year and had done two seasons of streaming hit “Mindhunter,” was a challenge, the lenser admits.

But, he says, “Easy is boring. It’s never easy with David – never. But it’s great to step in someone else’s sandbox and exercise new muscles.”

Besides, Messerschmidt adds, “I like working with older, established directors because they have a well-designed, established machine for how they want to make a film. And you come into it and you see, ‘Oh – he does it this way or she does it that way.’ It’s a wonderful way to learn, really, about film.”

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News