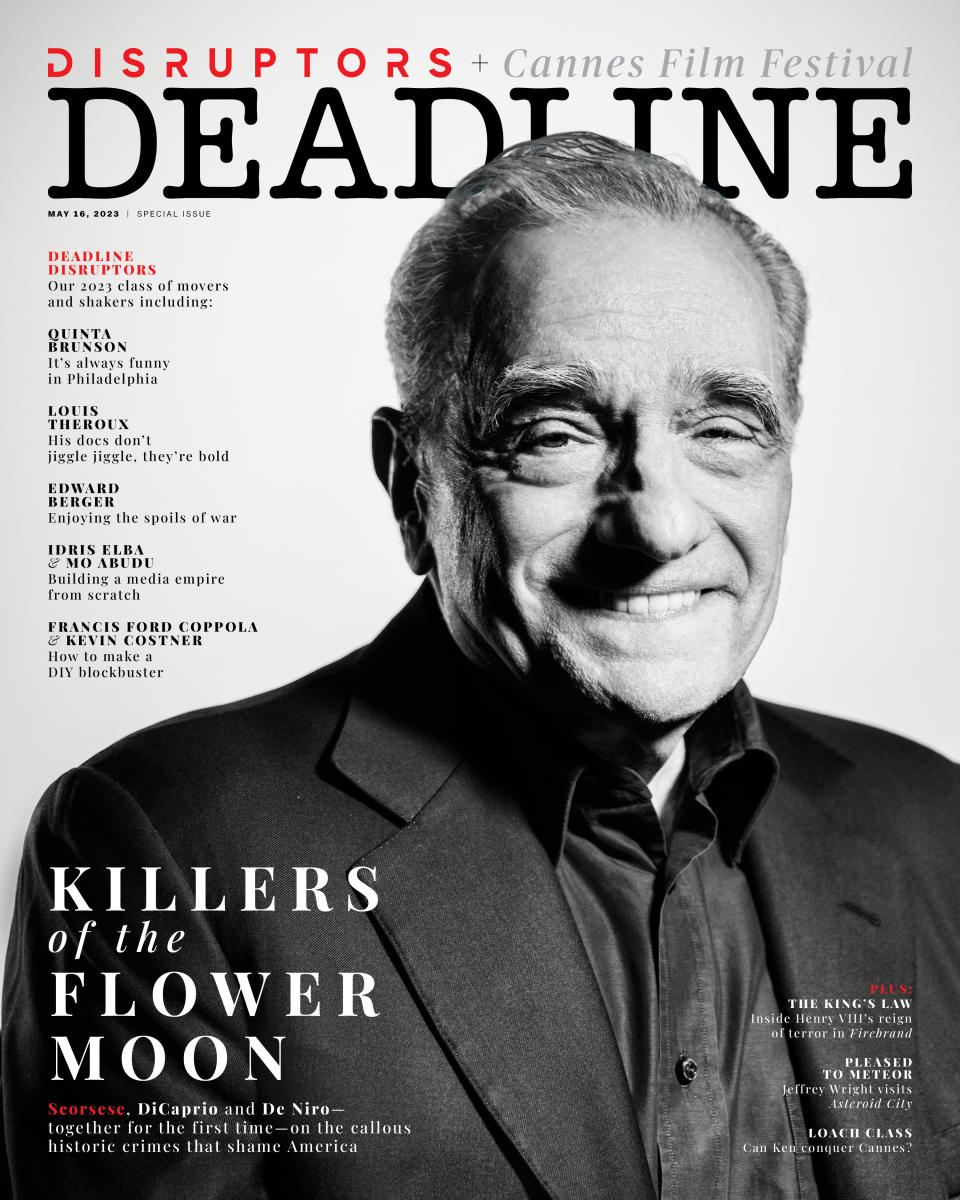

‘Firebrand’ On-Set Exclusive: Alicia Vikander & Jude Law In Karim Aïnouz’s Unvarnished Look At Henry VIII’s Final Marriage

It’s a solemn command from Firebrand’s first assistant director Lydia Currie: “When you bow to the king, bow straight down,” she announces. “Don’t look at him; you’ll get your head cut off.” The fearsome monarch Currie is referring to is Henry VIII, and on this particular day, Jude Law’s king is in an ax-swinging mood. The background artists on Karim Aïnouz’s set comply to orders and stare down at their toes. Before them, seated on thrones arranged on a raised plinth, is the potentate in question, and Katherine Parr, his queen.

Henry’s had a few wives. Katherine is his sixth and every time she opens her mouth, she’s in mortal danger. How does she survive? That’s the burning question asked by Firebrand, which Aïnouz describes as a “psychological thriller” ahead of its premiere Sunday night at the Cannes Film Festival. History tells us that Parr outlived her husband, but little is known about Parr after that, though she was the first woman in England to have a book published in her own name.

More from Deadline

Katherine was a smart woman who had to strategize in order to keep her head on her shoulders, says Alicia Vikander, the Academy Award-winning actress playing Parr. She knew exactly what she had to do “to live with a man who is like a beast” and “she needs to read him, constantly.”

Firebrand’s set today is the ancient Haddon Hall, built with local Derbyshire, England sandstone thick enough to retain 900 years’ worth of secrets within its walls. Aïnouz accompanies Vikander, wearing a grey tracksuit, to the Hall’s gardens to go through the scene planned for the day’s shoot: It’s to be a Maypole dance to welcome in the spring.

A corpulent person soon appears, bedecked in a bejeweled coat with a fox-head fur wrapped over his shoulders. “It has to be real otherwise it looks like teddy bears,” says costume designer Michael O’Connor. Before PETA becomes involved, he quickly adds, “They’re old cut-up fur coats, so they’re sustainable.”

The man with the wide girth continues toward the filmmaker and the actress. He’s having trouble with his legs and the walk is more of a wobble. It’s before 9 a.m. and a visitor wonders if the mystery man with whiskers on his square-jawed face is Law’s stand-in.

“It’s Jude,” Firebrand producer Gabrielle Tana says matter-of-factly. “There’s Alicia in her civvies. They’re all here to rehearse. That’s Karim’s process.”

Law fills the throne as he sits. White stockinged legs protrude from ruby-red robes. He stares at Vikander, who by now has partnered with Sam Riley, playing the cowardly courtier Thomas Seymour. They bow, heads down, then dance. Vikander, who studied ballet when she was younger, moves delicately as Karim and Law look on.

Law shifts his padded frame. He was up with the larks to be dressed in specially made undergarments of the period. “No zips and buttons,” says O’Connor, noting that Law’s undies had to be tied up with silk ribbons.

Such an endeavor signified immense wealth. “You couldn’t possibly dress yourself,” O’Connor scoffs. “Only those highborn and with money could afford to have an army of dressers to get you ready in the morning.”

Aïnouz wanted to work with O’Connor because of the costumes he created for Francis Lee’s Ammonite. The filmmaker asked O’Connor how they could make “Ammonite on this film, in terms of spareness, stripping it down.”

“I said: ‘Well, she’s scrabbling around for dinosaur poo on the South Coast, and this is the court of Henry VIII, so they’re not really related to each other.’ But he wanted to get into what happens behind closed doors. It’s about how to transpose his style onto this subject. He wanted to coarsen it up a bit,” says O’Connor, though there is some splendor.

Only thespians portraying powerful sovereigns in a major movie can wallow in such trappings nowadays. So it was that O’Connor and his team were up early to kit out Law in a full padded body suit and then dress him in finery before turning him over to Oscar-winning makeup and hair designer Jenny Shircore to pad his cheeks, Marlon Brando Godfather style, and attend to his coiffure.

Shircore has been on almost intimate terms with Law’s torso; painting it with makeup and measuring his padded posterior to ensure the buttocks tallied with someone else’s bare bottom, to use as a stand-in for a scene involving a horrifying sexual assault on Parr.

Tana admits that “a lot of actors were scared” of this Henry VIII. “He’s a murderer, a butcher,” she says.

“They didn’t want to have to go through that physical transformation, and all they could think about was that Hans Holbein portrait of Henry as this very stout, big thing,” she says. “They couldn’t get that out of their mind. There’s something very dark about that period and this Henry. But Jude relishes this, and he has totally embraced it.”

One of Aïnouz’s edicts is that on the set nobody talks to the actors except him. “So on the set, Jude is Henry,” Tana tells us.

She understands it. “It’s about protecting those characters. When they’re on the set that’s who they are. It’s his interactions with the actors and those interactions are sacrosanct,” Tana says. “He’s the director, he’s the auteur. They’re discovering their characters as they’re playing them.”

Aïnouz, too. Born to a Brazilian mother and an Algerian father who met at graduate school in the U.S., British medieval history hadn’t been on his curriculum growing up in Brazil. “Karim didn’t even know who Henry VIII was until I gave him the screenplay,” Tana says, which is why she wanted him to direct Firebrand.

She wanted a filmmaker who could look at other peoples’ stories “from the outside”. Tana knew this from watching the heart-wrenching betrayals explored in his films such as Futuro Beach and The Invisible Life, a success at Cannes in Un Certain Regard.

Tana notes how some British period films “fall into the same old tropes.” She says, “Karim doesn’t countenance tropes, but delights in all the things that are about the period.”

Like what? “In a way, the horrors of it,” she says with alarm. “It’s not romanticized, it’s a fascinating portrait of a horrible marriage. There was no way out of it for her. ”

And Aïnouz has been absorbed with the historical medical details relating to Henry’s painful venous leg ulcers. “The maggots, the leeches and all of that,” that physicians of the day applied when they opened the wounds to drain and air them, Tana says.

Shircore consulted with surgeons about venous ulcers so she could contract FX designers to build leg wounds oozing with a variety of matter that slithers and apply them to Law’s legs. “It’s all down to Jude,” Shircore says. “He knows what he wants. He knew he could achieve it.”

As with Aïnouz, Vikander came to Parr from an outsider’s perspective, though she confesses to a certain “unsaid pressure” in portraying a royal character. But “Karim has taken an artistic freedom in telling quite an intimate story about a relationship,” she notes. “He shows quite a domestic version of what happened at court.”

There’s also a coarseness in the court that Aïnouz puts on display at Haddon Hall. “We’ve really tried to strip down the costume drama,” Vikander says.

Although the great state rooms, minstrels’ gallery and the acres of terraced gardens are splendid to behold, they’re not as grand as the palaces down south. “We are not in the main castle of London,” Vikander explains, “because, and this was accurate during the time, the court has to escape the plague, so this is set much smaller. It’s like when the royal court goes camping for a while.”

Vikander studied Parr’s own writings to help get a sense of Parr’s life. “For me, it was a lot of trying to get in the head of this woman and to understand her faith in God. The question of not having faith almost didn’t exist.” Parr’s words helped give Vikander a realization. “Not only of Katherine, but of how women at that time lived and how they really came second. They were such a low-tier citizen.”

Vikander couldn’t comprehend how Parr could write long essays and poems about her fantastic husband, “And yet, at certain points of her life, he wants her dead. She’s in this very unhealthy and abusive relationship, but at some level it also needs to be functioning, and she was considered a good wife. I think it’s interesting to think about women in general, at whatever generation or time you’re in, you need to survive, so you also need to find your place in this reality and to find a way for you to not fully succumb to the tragedy that you are in.”

The stance Parr took often worked in her favor. Henry admired her intelligence to such an extent that he made her regent when he went with his army to France. “We really do play with the idea that she had quite a lot of influence on him,” she says.

We’re sitting in an outbuilding that has been turned into her green room, which she has brightened up with flowers.

The talk then turns to monsters. The ones who run the world now and how they relate to monsters in the past. “Henry was a monster and there are dictators like him living now,” she says, without identifying the 21st century culprits. Her question is, how would you survive? “How would a woman survive,” she corrects herself. “What would you say and how would you behave?”

A look back at Henry’s six wives suggests that history doesn’t really focus on the survivors. You don’t hear so much about Catherine of Aragon and Anne of Cleves, whom he divorced, but everyone remembers Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, who were executed, and Jane Seymour, who died shortly after childbirth. “Isn’t that sad?” says Vikander. “They’re only interested in the women if they’re dead.”

Best of Deadline

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News