We found unhealthy pesticide levels in 20% of US produce – here’s what you need to know

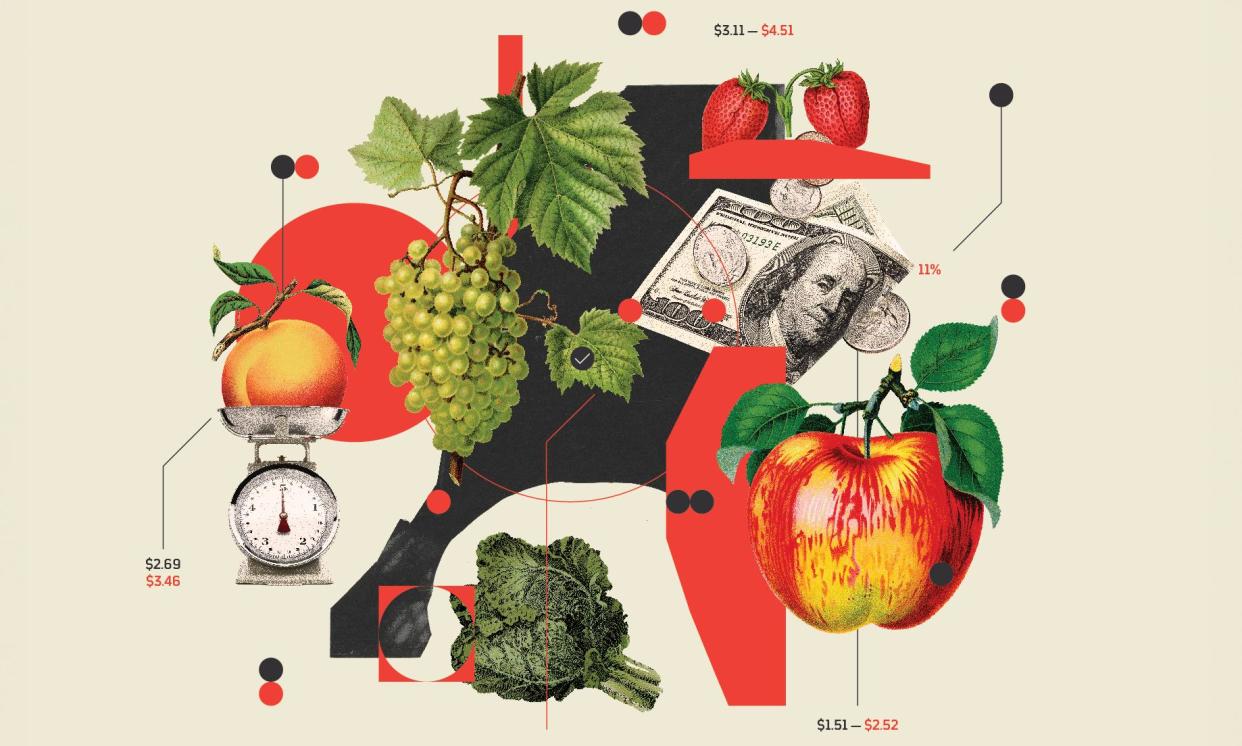

When it comes to healthy eating, fruits and vegetables reign supreme. But along with all their vitamins, minerals and other nutrients can come something else: an unhealthy dose of dangerous pesticides.

Related: Blueberries and bell peppers: six fruits and vegetables with the most pesticide risk

Though using chemicals to control bugs, fungi and weeds helps farmers grow the food we need, it’s been clear since at least the 1960s that some chemicals also carry unacceptable health risks. And although certain notorious pesticides, such as DDT, have been banned in the US, government regulators have been slow to act on others. Even when a dangerous chemical is removed from the market, chemical companies and growers sometimes just start using other options that may be as dangerous.

Consumer Reports, which has tracked the use of pesticides on produce for decades, has seen this pattern repeat itself over and over. “It’s two steps forward and one step back – and sometimes even two steps back,” says James E Rogers, who oversees food safety at Consumer Reports.

To get a sense of the current situation, Consumer Reports recently conducted our most comprehensive review ever of pesticides in food. To do it, we analyzed seven years of data from the US Department of Agriculture, which each year tests a selection of conventional and organic produce grown in or imported to the US for pesticide residues. We looked at 59 common fruits and vegetables, including, in some cases, not just fresh versions but also canned, dried or frozen ones.

Our new results continue to raise red flags.

Pesticides posed significant risks in 20% of the foods we examined, including popular choices such as bell peppers, blueberries, green beans, potatoes and strawberries. One food, green beans, had residues of a pesticide that hasn’t been allowed to be used on the vegetable in the US for over a decade. And imported produce, especially some from Mexico, was particularly likely to carry risky levels of pesticide residues.

Related: Can you wash pesticides off your food? A guide to eating fewer toxic chemicals

But there was good news, too. Pesticides presented little to worry about in nearly two-thirds of the foods, including nearly all of the organic ones. Also encouraging: the largest risks are caused by just a few pesticides, concentrated in a handful of foods, grown on a small fraction of US farmland. “That makes it easier to identify the problems and develop targeted solutions,” Rogers says – though he acknowledges that it will take time and effort to get the Environmental Protection Agency, which regulates the use of pesticides on crops, to make the necessary changes.

The way the EPA assesses pesticide risk doesn’t reflect cutting-edge science

Consumer Reports senior scientist Michael Hansen

In the meantime, our analysis offers insights into simple steps you can take to limit exposure to harmful pesticides, such as using our ratings to identify which fruits and vegetables to focus on in your diet, and when buying organic produce can make the most sense.

What’s safer, what’s risky, and why

Sixteen of the 25 fruits and 21 of the 34 vegetables in our analysis had low levels of pesticide risk. Even children and pregnant people can safely eat more than three servings a day of those foods, Consumer Reports’ food safety experts say. Ten foods were of moderate risk; up to three servings a day of them are OK.

The flip side: 12 foods presented bigger concerns. Children and pregnant people should consume less than a serving a day of high-risk fruits and vegetables, and less than half a serving a day of very high-risk ones. Everyone else should limit consumption of those foods, too.

To come up with that advice, we analyzed the USDA’s test results for 29,643 individual food samples. We rated the risk of each fruit or vegetable by factoring in how many pesticides showed up in the food, how often they were found, the amount of each pesticide detected and each chemical’s toxicity.

The Alliance for Food and Farming, a farming industry organization, pointed out to Consumer Reports that more than 99% of foods tested by the USDA contained pesticide residues below the Environmental Protection Agency’s legal limits (referred to as tolerances).

But Consumer Reports’ scientists think many EPA tolerances are set too high. That’s why we use lower limits for pesticides that can harm the body’s neurological system or are suspected endocrine disruptors (meaning they may mimic or interfere with the body’s hormones). Consumer Reports’ approach also accounts for the possibility that other health risks may emerge as we learn more about these chemicals.

Related: Kale, watermelon and even some organic foods pose high pesticide risk, analysis finds

“The way the EPA assesses pesticide risk doesn’t reflect cutting-edge science and can’t account for all the ways the chemicals might affect people’s health, especially given that people are often exposed to multiple pesticides at a time,” says Consumer Reports senior scientist Michael Hansen. “So we take a precautionary approach, to make sure we don’t underestimate risks.”

In our analysis, a fruit or vegetable can contain several pesticides but still be considered low-risk if the combination of the number, concentration and toxicity of them is low. For example, broccoli fared well not because it had no pesticide residues but because higher-risk chemicals were at low levels and on just a few samples.

Some of the most problematic foods, on the other hand, had relatively few residues but worrisome levels of some high-risk pesticides.

Case in point: watermelon. It’s very high-risk mainly because of a pesticide called oxamyl. Only 11 of 331 conventional, domestic watermelon samples tested positive for oxamyl. But it’s among those that Consumer Reports’ experts believe require extra caution because of their potential for serious health risks.

Green beans are another example. They qualify as high-risk primarily because of a pesticide called acephate or one of its breakdown products, methamidophos. Only 4% of conventional, domestic green bean samples were positive for one or both – but their pesticide levels were often alarmingly high. In one sample from 2022 (the most recent year for which data was available), methamidophos levels were more than 100 times the level Consumer Reports’ scientists consider safe; in another, acephate levels were seven times higher. And in some 2021 samples, levels were higher still.

You can eat a variety of healthy fruits and vegetables without stressing too much about pesticide risk

Registered dietitian Amy Keating

This is especially troubling because neither chemical should be on green beans at all: growers in the US have been prohibited from applying acephate to green beans since 2011, and methamidophos to all food since 2009.

“When you grab a handful of green beans at the supermarket or pick out a watermelon, your chance of getting one with risky pesticide levels may be relatively low,” Rogers says. “But if you do, you could get a much higher dose than you should, and if you eat the food often, the chances increase.”

In some cases a food qualifies as high-risk because of several factors, such as high levels of a moderately dangerous pesticide on many samples. Example: chlorpropham on potatoes. It’s not the most toxic pesticide – but it was on more than 90% of tested potatoes.

How pesticides can harm you

Pesticides are one of the only categories of chemicals we manufacture “specifically to kill organisms”, says Chensheng (Alex) Lu, an affiliate professor at the University of Washington in Seattle who researches the health effects of pesticide exposure. So it’s no surprise, he says, that pesticides used to manage insects, fungi and weeds may harm people, too.

While there are still open questions about exactly how and to what extent chronic exposure to pesticides can harm our health, scientists are piecing together a compelling case that some can, drawing on a mix of laboratory, animal and human research.

One type of evidence comes from population studies looking at health outcomes in people who eat foods with relatively high pesticide levels. A recent review in the journal Environmental Health, which looked at six such studies, found evidence linking pesticides to increased risks of cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Stronger evidence of pesticides’ dangers comes from research looking at people who may be particularly vulnerable to pesticides, including farm workers and their families. In addition to the thousands of workers who become ill from pesticide poisonings every year, studies have linked on-the-job use of a variety of pesticides with a higher risk of Parkinson’s disease, breast cancer, diabetes and many more health problems.

Other research found that exposure during pregnancy to a common class of pesticides called organophosphates was associated with poorer intellectual development and reduced lung function in the children of farm workers.

Pregnancy and childhood are times of particular vulnerability to pesticides, in part because certain pesticides can be endocrine disruptors. Those are chemicals that interfere with hormones responsible for the development of a variety of the body’s systems, especially reproductive systems, says Tracey Woodruff, a professor of environmental health sciences at the University of California, San Francisco.

Another concern is that long-term exposure to even small amounts of pesticides may be especially harmful to people with chronic health problems, those who live in areas where they are exposed to many other toxins and people who face other social or economic health stresses, says Jennifer Sass, a senior scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

That’s one of the reasons, she says, regulators should employ extra safety margins when setting pesticide limits – to account for all the uncertainty in how pesticides might harm us.

How to stop eating pesticides

While our analysis of USDA pesticide data found that some foods still have worrisome levels of certain dangerous pesticides, it also offers insights into how you can limit your pesticide exposure now, and what government regulators should do to fix the problem in the long term.

Eat lots of low-risk produce. A quick scan of this chart makes one thing clear: there are lots of good options to choose from.

“That’s great,” says Amy Keating, a registered dietitian at Consumer Reports. “You can eat a variety of healthy fruits and vegetables without stressing too much about pesticide risk, provided you take some simple steps at home.” (See Can you wash pesticides off your food? A guide to eating fewer toxic chemicals.)

Your best bet is to choose produce rated low-risk or very low-risk in our analysis and, when possible, opt for organic instead of riskier foods you enjoy. Or swap in lower-risk alternatives for riskier ones. For example, try snap peas instead of green beans, cantaloupe in place of watermelon, cabbage or dark green lettuces for kale, and the occasional sweet potato instead of a white one.

But you don’t need to eliminate higher-risk foods from your diet. Eating them occasionally is fine.

“The harm, even from the most problematic produce, comes from exposure during vulnerable times such as pregnancy or early childhood, or from repeated exposure over years,” Rogers says.

Switch to organic when possible. A proven way to reduce pesticide exposure is to eat organic fruits and vegetables, especially for the highest-risk foods. We had information about organically grown versions for 45 of the 59 foods in our analysis. Nearly all had low or very low pesticide risk, and only two domestically grown varieties – fresh spinach and potatoes – posed even a moderate risk.

Organic foods’ low-risk ratings indicate that the USDA’s organic certification program, for the most part, is working.

It’s always worth considering organic produce, [though] it’s most important for the fruits and vegetables that pose the greatest risk

James E Rogers, head of food safety at Consumer Reports

Pesticides aren’t totally prohibited on organic farms, but they are sharply restricted. Organic growers may use pesticides only if other practices – such as crop rotation – can’t fully address a pest problem. Even then, farmers can apply only low-risk pesticides derived from natural mineral or biological sources that have been approved by the USDA’s National Organic Program.

Less pesticide on food means less in our bodies: multiple studies have shown that switching to an organic diet quickly reduces dietary exposure. Organic farming protects health in other ways, too, especially of farm workers and rural residents, because pesticides are less likely to drift into the areas where they live or to contaminate drinking water.

And organic farming protects other living organisms, many of which are even more vulnerable to pesticides than we are. For example, organic growers can’t use a class of insecticides called neonicotinoids, a group of chemicals that may cause developmental problems in young children – and is clearly hazardous to aquatic life, birds and important pollinators including honeybees, wild bees and butterflies.

The rub, of course, is price: organic food tends to cost more – sometimes much more.

“That’s why, while we think it’s always worth considering organic produce, it’s most important for the handful of fruits and vegetables that pose the greatest pesticide risk,” Rogers says. He also says that opting for organic is most crucial for young children and during pregnancy, when people are extra vulnerable to the potential harms of the chemicals.

Watch out for some imports. Overall, imported fruits and vegetables and those grown domestically are pretty comparable, with roughly an equal number of them posing a moderate or worse pesticide risk. But imports, particularly from Mexico, can be especially risky.

Seven imported foods in our analysis pose a very high risk, compared with just four domestic ones. And of the 100 individual fruit or vegetable samples in our analysis with the highest pesticide risk levels, 65 were imported. Most of those – 52 – came from Mexico, and the majority involved strawberries (usually frozen) or green beans (nearly all contaminated with acephate, the pesticide that’s prohibited for use on green beans headed to the US).

A spokesperson for the Food and Drug Administration told Consumer Reports that the agency is aware of the problem of acephate contamination on green beans from Mexico. Between 2017 and 2024, the agency has issued import alerts on 14 Mexican companies because of acephate found on green beans. These alerts allow the FDA to detain the firms’ food shipments until they can prove the foods are not contaminated with the illegal pesticide residues in question.

The Fresh Produce Association of the Americas, which represents many major importers of fruits and vegetables from Mexico, did not respond to a request for comment.

Rogers, at Consumer Reports, says: “Clearly, the safeguards aren’t working as they are supposed to.” As a result, “consumers are being exposed to much higher levels of very dangerous pesticides than they should.” Because of those risks, he suggests checking packaging on green beans and strawberries for the country of origin, and consider other sources, including organic.

How to solve the pesticide problem

Perhaps the most reassuring, and powerful, part of Consumer Reports’ analysis is that it demonstrates that the risks of pesticides are concentrated in just a handful of foods and pesticides.

Of the nearly 30,000 total fruit and vegetable samples Consumer Reports looked at, just 2,400, or about 8%, qualified as high-risk or very high-risk. And among those samples, just two broad classes of chemicals, organophosphates and a similar type of pesticide called carbamates, were responsible for most of the risk.

“That not only means that most of the produce Americans consume has low levels of pesticide risk, but it makes trying to solve the problem much more manageable, by letting regulators and growers know exactly what they need to concentrate on,” says Brian Ronholm, head of food policy at Consumer Reports.

Organophosphates and carbamates became popular after DDT and related pesticides were phased out in the 1970s and 1980s. But concerns about these pesticides soon followed. While the EPA has removed a handful of them from the market and lowered limits on some foods for a few others, many organophosphates and carbamates are still used on fruits and vegetables.

Take, for instance, phosmet, an organophosphate that is the main culprit behind blueberries’ poor score. Until recently, phosmet rarely appeared among the most concerning samples of pesticide-contaminated food. But in recent years, it’s become a main contributor of pesticide risk in some fruits and vegetables, according to our analysis.

“That’s happened in part because when a high-risk pesticide is banned or pushed off the market, some farmers switch to a similar one still on the market that too often ends up posing comparable or even greater harm,” says Charles Benbrook, an independent expert on pesticide use and regulation, who consulted with Consumer Reports on our pesticide analysis.

We just don’t need [pesticides]. And the foods American consumers eat every day would be much, much safer without them

Brian Ronholm, head of food policy at Consumer Reports

Consumer Reports’ food safety experts say our current analysis has identified several ways the EPA, FDA and USDA could better protect consumers.

That includes doing a more effective job of working with agricultural agencies in other countries and inspecting imported food, especially from Mexico, and conducting and supporting research to more fully elucidate the risks of pesticides. In addition, the government should provide more support to organic farmers and invest more federal dollars to expand the supply of organic food – which would, in turn, lower prices for consumers.

But one of the most effective, and simple, steps the EPA could take to reduce overall pesticide risk would be to ban the use of any organophosphate or carbamate on food crops.

The EPA told Consumer Reports that “each chemical is individually evaluated based on its toxicity and exposure profile”, and that the agency had required extra safety measures for several organophosphates.

But Consumer Reports’ Ronholm says that approach is insufficient. “We’ve seen time and again that doesn’t work. Industry and farmers simply hop over to another related chemical that may pose similar risks.”

Canceling two whole classes of pesticides may sound extreme. “But the vast majority of fruits and vegetables eaten in the US are already grown without hazardous pesticides,” Ronholm says. “We just don’t need them. And the foods American consumers eat every day would be much, much safer without them.”

Read more from this pesticide investigation:

Can you wash pesticides off your food? A guide to eating fewer toxic chemicals

Kale, watermelon and even some organic foods pose high pesticide risk, analysis finds

Blueberries and bell peppers: six fruits and vegetables with the most pesticide risk

What’s safe to eat? Here is the pesticide risk level for each fruit and vegetable

Find out more about pesticides at Consumer Reports

Yahoo News

Yahoo News