Four Aboriginal spears repatriated to Australia after more than 250 years

Four Aboriginal spears that were brought to England by Captain James Cook more than 250 years ago have been repatriated to Australia in a ceremony at Trinity College in Cambridge.

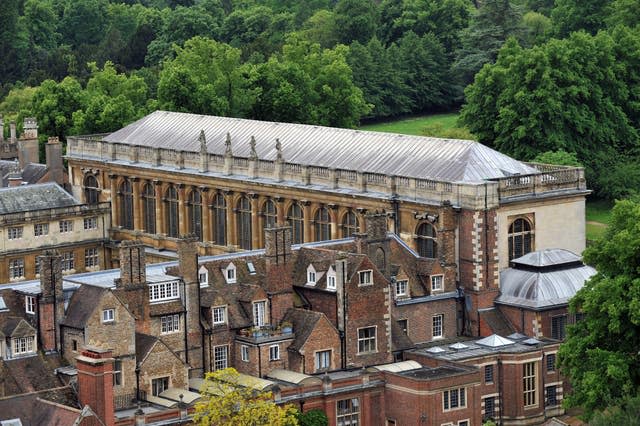

The artefacts were laid out on a table in the College’s Wren Library, with the three flags of Australia displayed at the front of the room, as a series of speeches were made.

Guests including direct descendants of people who were there on the day of the landing watched on from rows of seats, with the ceremony culminating in the signing of an official handover certificate by members of the Australian delegation, to a round of applause.

The permanent return of the spears to the La Perouse Aboriginal community was agreed in March last year, following a campaign and a formal repatriation request.

Dame Sally Davies, Master of Trinity, said it was the “right decision” to return the spears.

She added that Trinity College was “committed to reviewing the complex legacies of the British empire, not least in our collections”.

Captain Cook’s landing on the shores at Kamay (Botany Bay) in 1770 was resisted by Gweagal men – the indigenous Australian people of the area.

Soon afterwards, the British crew took 40 spears from a local camp, and four were later given to Trinity College, Cambridge.

Lord Sandwich of the British Admiralty, a Trinity alumnus, presented the four spears to Trinity College in 1771, soon after Captain Cook returned to England on the HMB Endeavour.

They have been part of the college’s collection since then, and from 1914 were cared for by Cambridge’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Noeleen Timbery, of La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council, appeared to wipe tears from her eyes as she spoke during the ceremony.

She thanked the College for “understanding that after 254 years it was time for the spears to come home”.

She vowed to protect and care for them.

In a lighter moment, Ms Timbery whispered to Dame Sally, who was hosting the event, before revealing that she had asked permission to take a selfie with her, and that Dame Sally had agreed.

Ms Timbery said “this is a big day”, her voice cracking with emotion, as she took the photo of herself and Dame Sally, with a library-full of guests behind them.

The four spears, which are all that remain of the original 40 spears, are regarded by the Gweagal as national treasures.

Gweagal people still use similar multi-pronged fishing spears.

Trinity College’s decision to return the spears followed years of talks between the MAA and the Aboriginal community at La Perouse.

Ray Ingrey, of La Perouse Aboriginal community group the Gujaga Foundation, said it was a “momentous occasion for our community”.

He said there had been a “long campaign to have the spears returned, there’s been about three generations working on this”.

“We’re finally here after all that time,” he said.

“We look forward to bringing them home.”

He continued: “The emotions are mixed – we’re very excited to be here but because it’s been a bit of a long time there’s many people that kicked off this campaign or wanted to see this happen who are no longer with us.”

Stephen Smith, Australian High Commissioner to the UK, said it was “an historic day”.

He continued: “In the modern era, collecting institutions are much more amenable to discussions with indigenous communities whether they’re from Australia or elsewhere.

“It’s been a great feature of the time that I’ve spent in the Australian community that many collecting institutions in the UK are keen to engage in those discussions about return of artefacts or repatriation of remains.”

Leonard Hill, interim chief executive officer of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, said that the 1770 incident was the “first encounter, first interaction between the British and Australia’s indigenous communities on the east coast of Australia”.

“As we understand from the records, a number of those indigenous community members approached the British as they were coming ashore and it resulted in an encounter where spears were thrown and shots were fired,” he said.

He said that “those first encounters were a defining moment for Australia”.

Professor Nicholas Thomas, director of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and Trinity Fellow, said that the spears were of “exceptional significance” and were “taken without the consent of the people”.

“It’s right now that they go back,” he said.

“They will mean more, their significance will be enlarged when they’re back in Australia.”

Some of the spears were returned temporarily to Australia in 2015, and again in 2020, for the first time since they were taken by Captain Cook, and displayed by the National Museum of Australia in Canberra, as part of two exhibitions exploring frontier encounters.

The spears will be displayed at a new visitor centre which is to be built at Kurnell, Kamay.

Until then, at the request of the La Perouse Aboriginal Community, they will be cared for by the Chau Chak Wing Museum at the University of Sydney.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News