‘Out of the frying pan and straight into hell’: Glen Campbell’s wild ride from poverty to insanity

On April 11 1966, Glen Campbell was drafted in as a last minute rhythm guitarist for a recording session with Frank Sinatra. Unable to believe that he was in the presence of his idol, he spent much of his time at the studio on Sunset Boulevard, in Los Angeles, gazing worshipfully at the man laying down the vocal for Strangers In The Night. The attention did not go unnoticed. “Who,” Sinatra hissed, “is that f______ guitar player?”

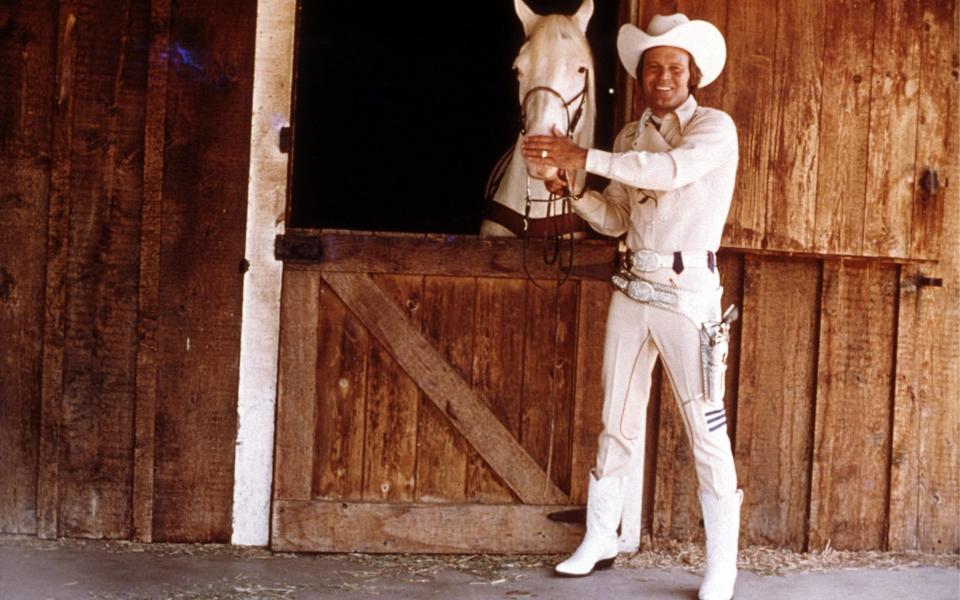

By the time his anonymous sideman had become a superstar in his own right, just two years later, Old Blue Eyes might well have remarked that Glen Campbell’s talents as a singer, no less, were equal even to his own. Along with an impeccable knack for phrasing and interpretation, the then 30-something Arkansan’s sense of implacable mournfulness – a quality later described by his fourth wife, Kim, as “a special sense of longing that lived in the centre of [his] soul,” – lent gravitas to the most unlikely material. In his telling, even the impossibly camp Rhinestone Cowboy sounded oddly forlorn.

In 2024, this ghostly quality is real. The new album Glen Campbell Duets: Ghost On The Canvas Sessions sees a man who has been dead for knocking on eight years now joined by a bevy of notables on a spirited reimagining of his final studio album, Ghost On The Canvas, from 2011. With contributions from Dolly Parton, Eric Clapton, Carole King, Elton John and Daryl Hall (among others), the cast list is indeed stellar. Inevitably, though, Campbell’s own oak tree of a voice refuses to be cowed into anything approaching shared-billing.

An appearance by Brian Wilson, on the song Strong, rekindles a working relationship that stretches back almost 60 years. After playing on such songs as Good Vibrations, in 1965 Campbell became a touring member of the Beach Boys for a year, after Wilson fell ill. The experience of providing harmonies, he said, added an octave to the top end of his vocal range. Appearing onstage alongside the group’s heartthrob drummer, the doomed Dennis Wilson, provided a glimpse of what was then a nascent phenomenon: pop hysteria.

“In Canada I saw one girl faint and I pulled her up [on stage],” he recalled in 2000. “Then I must have pulled seven or eight people up, they were all girls, screaming for Dennis. ‘Dennis, oh Dennis!’ We had to stop the show ’cos the girls were pressing up against the stage so hard.”

Likely, it was quite the culture shock for a self-described “country boy” from The Natural State. Born in 1936 into a sharecropping and farming family in the small Arkansan town of Billstown, two hours south of Little Rock, Glen Campbell endured the kind of Depression-era poverty that left a permanent mark on anyone who survived it. His father almost didn’t survive it. Unable to provide for his large family, Wes Campbell’s plan to kill himself in nearby woods was derailed only by a bounty of a dozen or so squirrels that he was able to shoot and bring home for dinner.

“The kind of poverty I knew as a boy wasn’t really any kind of living,” the singer would later say. “It was merely existing. We didn’t just endure poverty, we wore it. You could see it in the distant, fearful stare of my parents.”

Salvation came in the form of music. In a house without electricity, the sight of Wes Campbell popping waning batteries from the family radio into the oven, in the hope of revitalising their spent energy, led his son to remark that it was “a wonder they never exploded and blew up the whole house”. In circumstances as straitened as these, the gift of a seven-dollar guitar must have seemed no less luxurious than a Lear jet.

At age four, he began playing, and singing harmonies, with other family members. Ten years later, he was out on the road gigging in barrelhouses and fleshpots, first in Wyoming and then in New Mexico, playing sets that somehow encompassed material by both Glen Miller and Chuck Berry.

Even in the glare of blinding fame, the sense that Campbell was somehow an adaptable everyman never quite left him. Willing to fire and misfire every arrow in his showbiz quiver, he joked that his acting chops in True Grit “made John Wayne look so good he won his first Oscar”. In The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour, a network TV show watched by 50 million American viewers, he performed sketch comedy of a kind that made Joe Pasquale look like Lenny Bruce. This latitude had its limits, mind. “Shove it up your ass” was his response to a suggestion by a Capitol Records executive that he record a version of The Knack’s new wave hit My Sharona.

Remarkably, this bounty of extra-curricular activities seems not to have obscured the purity of that voice. Distilled on record, the magnificence of its lonely authority seemed able, even, to tune out the noise of a country in tumult over civil rights and a war in Vietnam. The entirely sublime Wichita Lineman, a song written on the fly by Jimmy Webb and recorded by Campbell in just 90 minutes, emerged in the same year as the assassinations of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. Gimme Shelter and Altamont lurked with menace just around the corner. But yet this strange and anomalous song about a solitary telephone engineer sold more than two million copies in the United States alone.

The country tradition of giving voice to hardscrabble characters from an America that might otherwise have gone unrepresented in popular culture paid him top dollar. The five million bucks Campbell earned in 1969 alone permitted the building of a 16,500 square foot mansion in Laurel Canyon, as well as the purchase of a house for his parents and a grocery store in Arkansas for one of his 12 siblings. He wasn’t done there either. Turns out he had more than enough money left over to really let rip.

The Devil, it seems, finds work for both idle and busy hands. Certainly, neither a redoubtable work ethic or Campbell’s strong and sincere adherence to Christianity were enough to protect him from the routine ruinations of an entertainment business awash with powders and booze. Even without the luxuries of money and indulgence, he might well have struggled. The branches of his family tree grew wild with alcoholism. At home in his new pile in LA, he read from his Bible, every night, while slugging shorts of whiskey and snorting bumps of cocaine.

“I have no excuse for it,” he once said. “I just got suckered into it. I was over 21.” Again, though, he had his boundaries. “[One time] I was in a house where they were freebasing cocaine, so I thought I’d try some. The rush, can you imagine? I thought I was going to die. I laid face down on a couch and prayed for six hours, just laying there. I never did that again. It’s like taking a gun and shooting it through your hand. You don’t do that twice.”

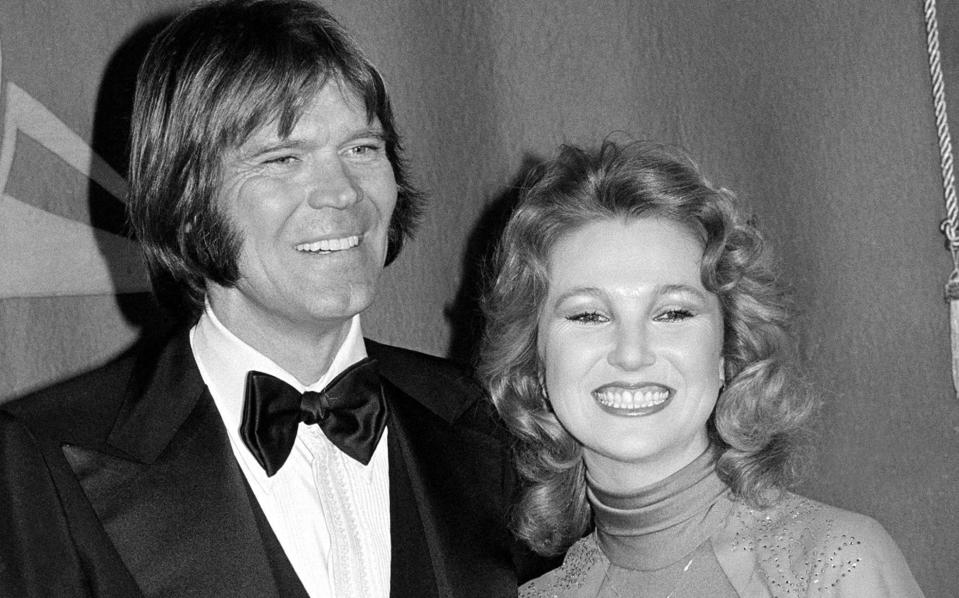

Sticking to nasal ingestion failed to ensure that his life choices were always wise. After decoupling from his third wife, Sarah, he embarked on a – quote unquote – tumultuous relationship with the outlaw country singer Tanya Tucker. “Out of the frying pan and straight into hell,” was how Campbell described his direction of travel. Supermarket tabloids feasted on the pair’s very public dysfunction. Windows smashed, hotel rooms trashed, teeth on the floor. Evidently, life was getting out of hand, especially in LA. “Everybody was a liar,” he said. “Everybody was doing cocaine. Everybody was denying it. Everybody was schtupping everybody’s little sister. That’s why I moved out.”

He flitted to Phoenix and took up with a fourth wife who was half his age. For the young Kim Woollen, a dancer with the Rockettes at New York’s Radio City Music Hall, the bewildering transition to hopping with the celebrity jet-set at such far-flung locations as Sun City, in the phoney South African state of Bophuthatswana, began at once. Very suddenly, the 20-something plus one was on first name terms with Sean Connery, Johnny Mathis, Joe DiMaggio, Ernest Borgnine, Telly Savalas and more.

Away from prying eyes, though, the torment was predictably unpredictable. As Dr Jekyll, the sober Glen Campbell was kind and funny, humble and warm; as the soused Mr Hyde, however, he was much more than a handful. Rebutting his protestations that a photograph taken from the neck-down in which he could be seen fast asleep wearing trousers soaked with urine was in fact an image of some other unfortunate, the newish Mrs Campbell replied “well he was wearing your clothes, then”. The problem of her husband never remembering the horrors of the night before was overcome by secretly taping one of his many drunken tirades. Turns out that voice of liquid velvet wasn’t always so pleasing after all.

“Many nights after a show we’d return to our hotel room hand in hand and make love, only for Glen to leave the room claiming he needed to talk to the band,” Kim Campbell wrote in her memoir Gentle On My Mind. “He’d come back hours later, barely able to walk. I’d help him to the bathroom, undress him, and put him to bed. Other times he returned to the room and forced me to listen to him pontificate for hours. On those nights I knew that coke was talking, and, believe me, though it’s nonsense, coke has a lot to say.”

Elsewhere in her remarkably wise book, she writes that “I fell into the role of caregiver, a role that I maintained for the rest of our relationship. I am glad for that role, I am ambivalent about that role, but it is a role I came to accept. Early on, I saw that someone needed to save this man from himself.” This statement, I think, is as poignant as any issued in song from the lips of Glen Campbell himself.

She got him there in the end, though. Glen Campbell quit cocaine after his wife threatened to leave him in the wake of yet another early morning encounter with a man whose eyes were wider than the Arizonian sky. Notwithstanding a relapse in 2003, drinking was eschewed in 1987. He held on to his faith, of course, not seeming to mind that the God in Whom he so fervently believed bestowed blessings and curses with equal abandon. Speaking to USA Today following a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease that would soon draw the curtains on his life, he accepted his lot with graceful good humour. “There’s a lot of things I didn’t ever want to remember, anyway,” he said.

But even this terrible condition was no match for the purity of his calling. Shortly before his death in the summer of 2017, Glen Campbell serenaded his wife and doctors with a song in his room at a residential care facility in Nashville. The words, such as they were, were gibberish, but the melody soared high above his diminished circumstances. At the end of the performance, he took a bow, curled his lip, and muttered “thank you very much”.

Glen Campbell Duets: Ghost On The Canvas Sessions is on release now

Yahoo News

Yahoo News