Giorgia Meloni’s Worlds Are About to Collide

(Bloomberg) -- Italy’s prime minister knows her reputation precedes her. She’s also learned that can work to her advantage: “When they paint you as Attila the Hun, you might reassure people simply by being Giorgia Meloni.”

Most Read from Bloomberg

US Inflation Broadly Cools in Encouraging Sign for Fed Officials

Blinken Casts Doubt on Cease-Fire Hopes After Hamas Responds

Britain’s ‘Quiet Quitters’ Are Costing the Economy £257 Billion

Though she takes a gentler approach to disarming critics than the fifth century despot, she has been swift to set the agenda in Europe. She’s won round a skeptical Joe Biden and earned the grudging respect of Olaf Scholz and Emmanuel Macron. While the premiers of France and Germany were humbled by the European elections, she stands out as a rare leader on the front foot as she prepares to host the Group of Seven summit this week.

Through her pragmatism Meloni’s consolidated more than votes. She’s gained the respect of leaders who were, as recently as two years ago, suspicious of her origins in Italy’s euroskeptic hard right. But, while her eminence on the international stage owes to a radical break with her own past, that of Italy may yet catch up with her. After a benign period where the country’s had great success wooing bond investors, a mounting debt pile more reminiscent of the bad-old-days is threatening to cause ructions.

Qui per leggere la versione italiana di questo articolo.

The task of repairing public finances augurs decisions that could imperil the loyalty of voters who’ve just returned her party to the European parliament with an improved tally of seats, and might even force a standoff with the neighbors she has otherwise done so much to impress.

Officials at the finance ministry are painfully aware of the growing strain on the country’s coffers, people familiar with the matter said, and expect to take action imminently either through cuts to spending or extra taxes. But they were under strict orders to do nothing, and say nothing, until after the weekend’s elections, the officials added, asking for anonymity because they weren’t authorized to speak publicly.

This account of Meloni’s attempts to consolidate her position as Europe’s foremost right-wing politician is based on interviews with dozens of people familiar with her thinking.

As the young leader of Azione Giovani, the youth movement of the hard-right party that rose from the ashes of Italian post-war fascism, Meloni would insist that her schedule be faxed to her the day before, according to a long-time ally. While her politics may have shifted, these exacting habits have not: as prime minister she continues to draw observations for her fastidious note-taking.

She has left nothing to chance at the G-7, tying up as many loose ends as possible and closing in on a major announcement on what to do with Russian assets that were frozen after the 2022’s invasion of Ukraine. There is a risk that all that careful choreography is undone by the political chaos recently unleashed in France.

And looming in the background is a curveball even Italy’s fastidious prime minister may not be able to control. The European Commission is poised to declare the country to be in breach of bloc-wide spending rules, turning the spotlight on its dysfunctional economy.

By failing to keep its deficit within bounds, Italy is in good company. But its wayward euro-zone peers include a couple of borderline cases that could be spared, people familiar with the matter said. An unfortunate distinction for the EU’s 3rd biggest economy is that its debt is projected to keep expanding.

A demanding adjustment could spell trouble for Meloni and complicate relations inside her coalition, if ministries’ spending is reined in. Her finance minister Giancarlo Giorgetti has privately told allies that he doesn’t want to take the blame when Brussels comes calling, Bloomberg reported last week.

Officials unveiled a deteriorating fiscal outlook in April, when they acknowledged the trajectory for Italy’s debt had shifted to one where borrowing will rise for years to come. The IMF now reckons that Italy’s debt pile will breach 140% of output as soon as next year, while it sees that ratio in the wider euro zone falling slightly to 88.3%.

And just when last thing Italy’s economy needs is an exogenous shock, France’s Macron has engineered drama which is threatening to contaminate his neighbors. The yield premium that investors demand to hold Italian 10-year bonds over those of Germany suddenly rose to the highest in four months yesterday, amid uncertainty about France’s snap election.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen will attend the G-7 talks at a resort overlooking the Adriatic Sea. She and Meloni have forged an unlikely friendship, with Von der Leyen, who remains well placed to retain the presidency, signaling in advance of the elections her openness to formalizing a partnership with parts of Meloni’s bloc. It’s a sign of how far Italy’s premier’s evolved — but also of how the center of European politics has shifted toward her.

In her short tenure she’s worked hard to project a renewed sense of importance for Rome in the European Union, in part by making signature policies such as her plan to process asylum applications in Albania, and the Mattei plan for Africa, marketable to other bloc capitals, according to people with knowledge of her government’s diplomatic efforts.

The Albania arrangement has drawn controversy but also unlikely acceptance, with even Germany’s center-left chancellor committing publicly to study the model.

No one else at the EU’s top table has demonstrated an ability to so easily cross ideological divides and do business with Scholz, von der Leyen and even Hungary’s Viktor Orban at the same time. Meloni was instrumental in demolishing the latter’s opposition to EU aid for Ukraine, even though her own domestic coalition partners retain the warmer stance toward Russia that’s at odds with the policy she was enforcing. In recognition of her pragmatic transatlanticism she and Biden have developed a very close relationship, according to one US official.

Beyond her dexterity on the world stage, Meloni attracts reluctant admiration from ideological opponents at home. Opposition figures and even left-leaning civil servants repeatedly sound out one message: you may dislike her politics, ma è brava, but she’s good.

That feeling is not always returned. You were either alongside her 30 years ago hanging posters as a student politician or you can’t be on her team now, one person said, citing the experiences of several journalists affiliated with the public broadcaster who’ve attempted to switch allegiances to her party under her mandate — and been rebuffed.

The paranoia represents an accurate read of sentiment toward her in large swathes of the country. Even though her party’s 29% share of the vote in EU elections represents a mild improvement on the polls that brought her to power, support for the center-left parties opposing her coalition has grown faster.

This leaves the prime minister turning more isolated and distrustful, according to those around her. This, the people say, makes it hard for her to delegate, with every decision needing her approval before it can be moved forward. That could herald problems when it comes to orchestrating a sensitive economic adjustment.

Click here to listen to Donato Paolo Mancini discuss Meloni’s challenges on the Europe Daybreak Podcast.

Until now, Meloni has seemed to have it all figured out. She is, in her very own words, “that bitch.” At least, that’s what she told a regional governor last month, after he’d been caught — on a hot mic — bestowing the epithet on his country’s first female prime minister.

That ability to turn barbs into strengths is one way she’s retained the adoration of her populist base even while cleaving to EU orthodoxy. There are signs that she may yet apply this tactic to the economy. Rather than letting the public finances undermine her, she’s already started to seed the argument that they’re a reason to strengthen her mandate.

In late May, the prime minister acknowledged Italy’s precarious fiscal situation, but blamed it on the constant need to secure trade-offs between coalition parties.

Meloni said: “When you have, on average, a political horizon of about a year and a half, you can’t start a strategy, you can’t invest. What you can do is spend — spend to attain immediate consensus.”

The solution she’s been campaigning for is to strengthen the office of prime minister.

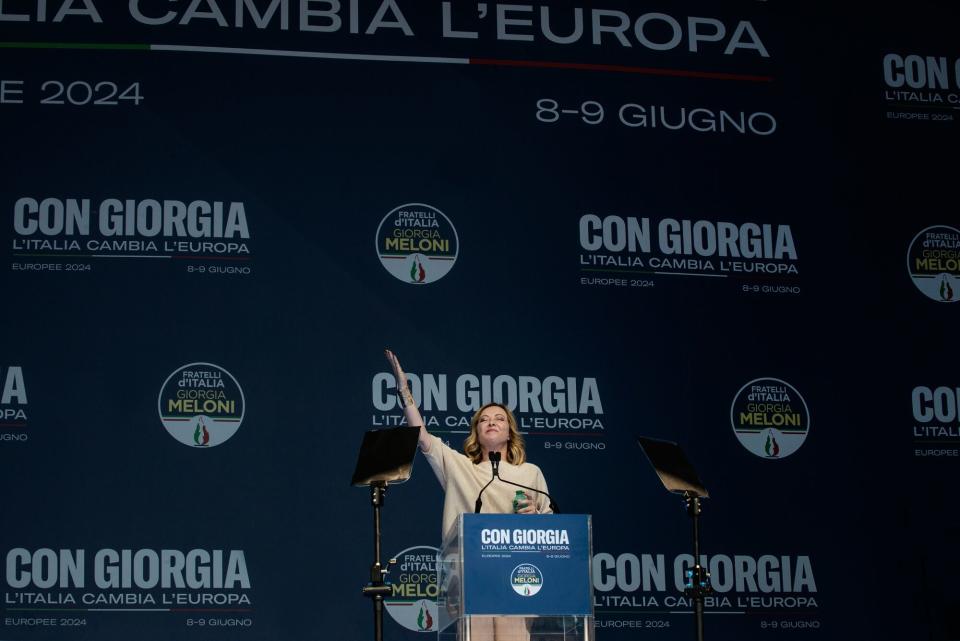

That could deal the final blow to the underdog persona she knows is key to retaining support at home. “I have always been and always will be proud of being an ordinary person,” she told party members at a recent rally, amid roaring chants of “Giorgia, Giorgia.”

--With assistance from Jorge Valero, Alessandra Migliaccio, Chiara Albanese, Michael Nienaber, Alberto Nardelli and Giovanni Salzano.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

China’s Economic Powerhouse Is Feeling the Brunt of Its Slowdown

As Banking Moves Online, Branch Design Takes Cues From Starbucks

Food Companies Hope You Won’t Notice Shortages Are Raising Prices

The World’s Most Online Male Gymnast Prepares for the Paris Olympics

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News