Girls Aloud are back – and pop will be better and weirder for it

It came late last week; the news every pop fan worth their salt had been waiting for. The news every pop fan who recognises that Biology is one of the greatest bangers of the 21st century, and whose keen standom extends to the knowledge that the now-mononymic Cheryl has an intense phobia of cotton wool, was dreaming of: Girls Aloud are reuniting, with tickets on sale today.

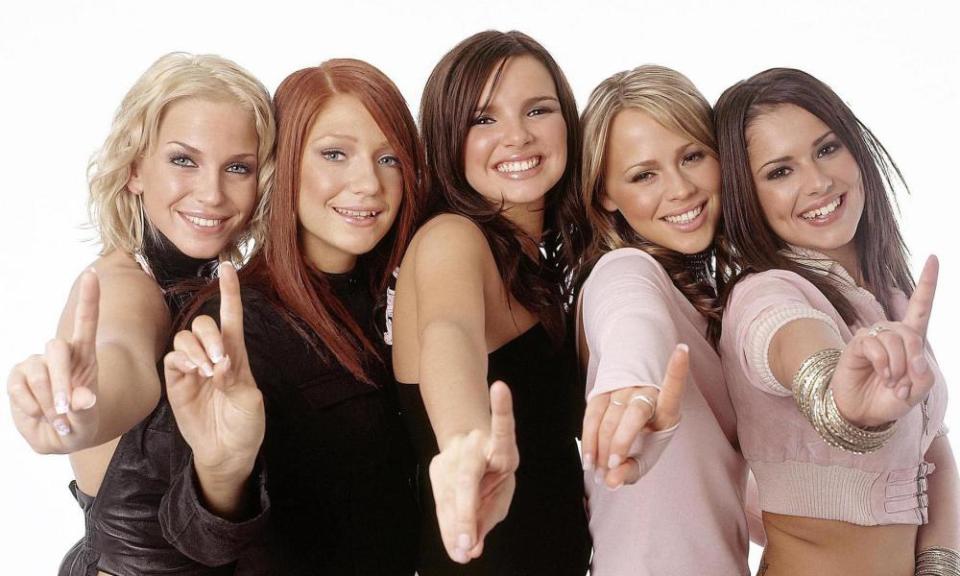

Along with the Shangri-Las and the Runaways, Girls Aloud are one of the greatest girl bands of all time. As someone born in 1989, it was probably the Spice Girls that I should have been obsessed with. Sure, I had the collectible photo album now doing a brisk trade on eBay. I could do the signature leg-kick of fellow scouser and ardent LFC supporter Mel C. But the Spice Girls never spoke to me.

That Girls Aloud did, a group born from a music talent show I did not watch, at a time when I was a moody mid-teen more accustomed to listening to Interpol’s Specialist for the 15th time in a row, is testament to a seductive combination of brilliant music and charismatic personality.

The band were never meant to be the breakout stars of Popstars: The Rivals, ITV and Simon Cowell’s twist on their previous show, Popstars (whose underdogs would also go on to enjoy surprise success in the form of Liberty X). The format reboot was simple: the show’s boyband and girl band would go head-to-head for the 2002 Christmas number one slot.

It initially looked as though the excruciatingly named One True Voice would win. But that seemed less likely when their insipid cover of a not-amazing-to-start-with late Bee Gees album track was chosen as the boys’ contender, while Girls Aloud came bursting out the gate with the surf riffs and drum’n’bass pulsating energy of Sound of the Underground (with a gritty video shot in a cavernous abandoned warehouse to boot). The latter song hit No 1, and would stay there for four weeks. Girls Arrived.

Much of the band’s phenomenal success and longevity – 21 Top 10 singles, four of them No 1s – was, undoubtedly, down to the genius production outfit Xenomania. Responsible for Sound of the Underground (apparently inspired by late-90s dance hit Addicted to Bass and nursery rhyme The Wheels on the Bus), Xenomania, founded by producer Brian Higgins, would go on to become permanent collaborators.

In Higgins’ hit factory (actually a Grade II manor house in rural Kent), he, the group and chief songwriter Miranda Cooper would squirrel away, recording songs as glorious and experimental as Biology (which kicks off with a sample of the Animals, eschews the usual linear verse-chorus structure, and changes direction three times); Love Machine (recorded in 18 parts, melding rockabilly and 80s synth sensibilities); and the frankly batshit Sexy! No No No (electro-punk with a Nazareth sample).

But it’s lesser-known album cuts that hold a special place in my heart. The barmy Miss You Bow Wow on their final album, Out of Control, or its stablemate Love Is The Key, which goes from creepy hymn intro to line-dancing country swagger to a harmonica solo played by Johnny Marr. Or Graffiti My Soul, which sounds like Run DMC and Aerosmith’s Walk This Way performed by Willie Nelson in the Hacienda, then remixed by the Prodigy.

Even the so-called flops, such as Long Hot Summer, which still reached No 7, were a cut above most chart fare, and the songs which weren’t as avant garde (the Spector-inflected The Promise, written in seven minutes; the ballad Life Got Cold) were nevertheless outstanding examples of their respective genres.

But the “girls” themselves were crucial. Though sometimes hesitant in the face of Xenomania’s more outre instincts (Nicola Roberts worried about Sound of the Underground because “we didn’t have drum and bass up north at the time”) they have multiple songwriting credits, including on four of the best tracks from Out of Control. As evidenced by their jump-through-hoops talent show origins, each could actually sing, possessing distinctive vocal styles that complemented Xenomania’s jigsaw-like process.

But my love for the band was never confined to the recording booth: these were five extremely likable young women navigating an epoch of tabloid misogyny and burgeoning online snark. Amid the perennial hazard of the paparazzi upskirt shot – and Roberts being so absurdly bullied for her alabaster skin – their headstrong northern (or Northern Irish in Nadine Coyle’s case) attitude, wit and grounded sense of humour remained intact. In 2009, when the band won the cult music site Popjustice’s Twenty Quid Music Prize – a fun but nonetheless sincere rival to the elitism of the Mercury – Roberts turned up to a pub to collect it.

I listened to pretty much every band indie-grunge label Sub Pop put out in the early 00s – but I’d never been to Seattle. I loved late 90s hip-hop, had the posters on my wall, but was I 100% sure which was, in fact, the crip side? Flat vowel sounds and a love of tequila shots, though – relatable. The band’s 00s-defining sartorialism of tiny handbags, BaByliss-straightened hair and spaghetti tops – unfortunately, also very relatable.

The feeling that one could easily be mates with this lot was only accentuated by their hilarious turns on fly-on-the-wall E4 series Off the Record (Cheryl absolutely not giving a shit about climbing a hill in Athens for a view she could “see in pictures”), or Ghosthunting with … Girls Aloud (Roberts point-blank refusing to engage in a seance, which: fair enough).

I saw the band live four times, including a hugely emotional last ever performance as a five-piece, in Liverpool; and as part of the weirdest lineup outside a royal jamboree, supporting Jay-Z and Coldplay at Wembley – where they absolutely held their own. And though their shows incorporated the sort of blockbuster set-pieces and costumes that have become de rigueur in today’s Eras era, neither distracted from an incredibly solid set list energetically performed, with clear adoration for their fans, especially when playing their home towns.

In total, the band released five studio albums and two compilations (all certified platinum), as well as two live albums. Not only were they beloved by the likes of me and Popjustice, but they earned the respect of mainstream rock-oriented publications such as NME and Q, not unknown for sneering at anything “manufactured”, and ostensible arbiters-of-cool Pitchfork. As well as their collaborations with Johnny Marr, the likes of Peter Hook, Bloc Party and Arctic Monkeys professed a love for the band (the last even covered Love Machine on Radio 1’s Live Lounge). The entire time, I never had a favourite – or least favourite – member.

Their post-Aloud careers have been assorted. Cheryl went on to have five No 1 singles and came full circle by judging an ITV talent show. Coyle released solo music, opened a Los Angeles pub and gave us one of the most memed ever moments of television. The ever level-headed Kimberley Walsh has carved out a successful second life as a stage actor and presenter. Roberts released an exquisite solo album, Cinderella’s Eyes – a joyous amalgam of electro-pop, disco and even rap – and started a makeup line.

And then there was Sarah Harding. The vivacious rebel with the cropped blond hair, who’d always worked her arse off whether a college student in Stockport, or a BT call-handler, or a Pizza Hut waitress, or writing a memoir, whose rowdy reputation (“it’s about time!” she yelled upon a Brit awards win) was undercut by her delicate harmonies on, in particular, Whole Lotta History and The Promise. Harding died of breast cancer aged 39, and it is in her memory the 2024 reunion tour is dedicated.

That Harding’s obituaries focused, in some cases almost exclusively, on the erratic times in her personal life was poor testament to her contribution to the glorious, joyous, invigorating pop history of Girls Aloud. Or, as of May next year, its present. Reunion tour? I’m ready – and I say that with some determination.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News