Do girls really prefer to play with dolls? Scientists think they’ve solved this mystery of childhood

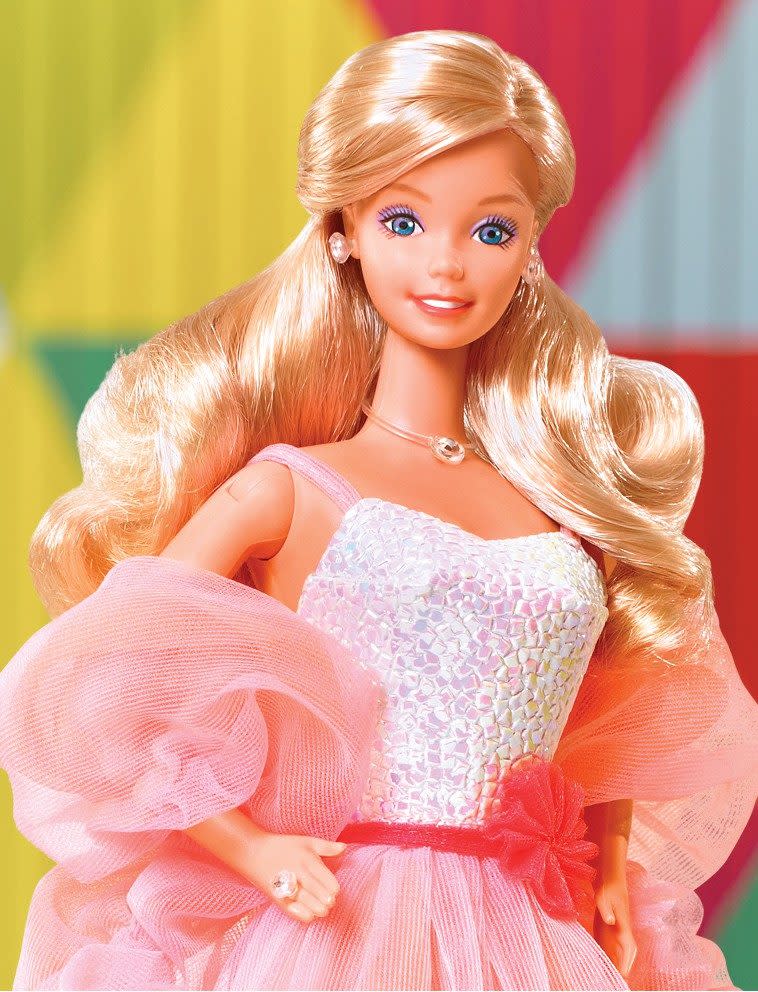

Why do we think that girls love dolls? Plaything, prisoner, best friend, victim, cipher, mirror: whatever a doll can be is eerily mapped onto what we think of women. At the Design Museum’s Barbie exhibition, stuffed with more than six decades of memorabilia (from rare Dreamhouses to 1992’s global hit Totally Hair Barbie), you too can stare into her delicate, painted eyes – and try to make sense of modern girlhood.

I’ll admit, writing about sex differences in toy preferences initially gave me pause. For one, dolls have always creeped me out. I have young children and simply have to accept that there are two dozen plastic faces, ever wakeful, in my house while I sleep. What’s more, in today’s culture wars, there are few things weaponised so effectively as gender and children.

Then again, most of us worry about our children. No parent I’ve ever met, “woke” or not, is happy with the endless sexist rubbish that is blasted at our daughters. Yet none of us seems entirely sure of how to fix it, either. (Abandon the pink and blue? Go for a nice mauve?) The question of gendered toys, then, is an important one – it goes to the heart of what we want for children. Do girls play with dolls because they’re girls? Are dolls sexist? And can science help us figure this out?

For scientists, “play” is a tricky subject. Though it seems to have several functions, many biologists believe that play is something a young animal does in order to practise the skills they’ll need later. “Play biting” is something wolf pups instinctively do, and when they’re older, they’ll use their bite to take down prey. Similarly, we’ve long assumed that “caretaking” play (be it juvenile female chimps cradling and patting sticks – as Harvard researchers observed in 2010 – or girls who love pushing prams around) also fell under this category of “practice”: preparation for becoming a mother. This idea fits neatly into the stereotype that girls prefer to play with dolls, particularly baby dolls, since they are preparing, as any young she-mammal would, to perform the many roles of motherhood.

If that all sounds slightly misogynist, you’re not wrong. While we’ve often assumed boys prefer to play with trucks, no one has ever thought this meant they were destined for a life driving lorries through the Midlands. For her part, Barbie was famously made for little girls in 1959, with a revolutionary twist: this doll is no baby. If girls could play with a doll that could have any job, Barbie’s designer Ruth Handler thought, couldn’t they imagine themselves having those jobs? And if the doll’s design, including its huge breasts, and waspish waist that could never house intestines, was quietly modelled after a German tobacco-shop gag gift – a mini sex doll – well, mothers didn’t need to know that.

So a toy originally designed for horny men became part of the foundation of Western girlhood for the next half-century – with more than a billion Barbies sold. But maybe that shouldn’t be surprising. “Dolls” can mean many things. Action figures are dolls. If you stop to think about it, “girls play with dolls and boys play with trucks” is a deeply weird idea. But it’s been reinforced by psychological science for almost as long as Barbie’s been around. The real differences run deeper.

Moving swiftly past the “dolls are practice for motherhood” model into the realm of better science, a number of psychologists and behavioural neuroscientists have conducted studies demonstrating that children do seem to be split by sex in the sorts of toys they like to play with. By the age of one, male children appear to prefer “masculine” toys – specifically, things that move, such as trucks, and system-focused things, like building blocks, whereas females are more likely to grab “feminine” toys, such as dolls, which suggest more imaginative, character-based play.

A whole subfield of developmental psychology has sprung from these observations, asking questions such as: Is the “male brain” more “systemising”, and the “female brain” more empathetic, social, emotional? (That’s psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen’s bailiwick – though, to his credit, he doesn’t think one needs to be biologically male to have a “masculine” brain.) Does social influence drive this difference, or is it a cognitive blueprint? Is it that males advance slightly faster in early motor skills – kicking and squirming, moving those limbs about – and this makes movement more appealing? (For what it’s worth, males don’t learn to walk faster than females, so for all their squirming, the actual payoff is unclear.) Aren’t males ever-so-slightly better at spatial logic? And do female brains mature a touch faster, helping them reach cognitive milestones sooner than their male peers? (After all, imaginative play is cognitively more difficult.) Does exposure to hormones, even in the womb, help explain these differences?

This thinking has even been extended to monkeys, testing whether adorable male baby macaques are somehow led by their penises, like a divining rod, towards a preference for cars over dolls. But, fascinatingly, a recent paper by U C Davis researchers revealed an important flaw in this gender-mess of a field: a number of studies, in human and non-human primates, had been testing preference in groups, or with the presence of a parent or researcher in the room. But when you put a young macaque in a room alone with all sorts of different toys, there’s no difference in categorical toy preference between males and females. In fact, the one sex difference that did emerge from that study was the opposite: when they did interact with a doll from their many toy choices, the males interacted with the doll more than the females did.

So, removed from the blaring signalling from members of their social group, the males didn’t prefer the cars. The females didn’t prefer the dolls. It wasn’t – at least in this experiment – a matter of one’s biological sex. In monkey-land, maybe male brains don’t solely prefer to play at systemising, and females aren’t especially empathising, but they’re both influenced by social signals from others.

Why does individual, free-choice toy preference matter? And how much blame, then, can we lay on Barbie? Quite a lot, for the first, and very little, for the second. Even when they’re trying not to, most caretakers give off all kinds of signals of approval or guidance around anything a young child will do, and most children learn those signals and respond. If a parent were in the room, it would be hard to know if the child were picking a certain toy in part to please them, or because they like playing with certain toys with that parent, which might not be true with a different adult or by themselves (I admit, I’m a bit better at playing with musical instruments with my children than with cars. I’m just not that good at vroom. I can do it, but, somehow, I think my son knows I am faking it.)

It’s becoming increasingly clear that the sort of toys parents provide to their children at home influences the sorts of toys those kids come to prefer. Since very few studies work with newborns who haven’t yet encountered toys at all, prior exposure by influential figures (aka their parents) can’t be ruled out as a major driver. And of the many documented cases of the ways we unintentionally behave differently around our female and male children, it’s rarely just about toys.

Even for basic skills such as how spatially aware a child might be (one of the few reproducible functional brain differences between human males and females is that males tend to be slightly faster at spatial logic – like rotating a shape in one’s mind and correctly answering questions about it), a 2017 study by American psychologists shows parents’ use of spatial words (such as “circle”, “bent” and “edge”) directly influenced the child’s use of spatial words. And, yes, the parents typically used those words differently between boys and girls.

What the brains and behaviour of social primates should be known for, in other words, is their plasticity. We’re built to be flexible. This should be especially true for things that shape behaviour which maintains local social norms over generations – things that are, by their nature, cued by local example, disapproval, or approval. To put it in the simplest terms, I’m saying that quite a lot of girlhood is probably learnt. The same is true for boyhood. Whatever is innate, and surely there’s some, is always exposed to the influence of the child’s powerfully social world, which effectively comes into being from day one. We learn how to be. We learn what’s fun. We learn whether or not it’s cool to vroom, depending on what sort of person our parents (consciously or unconsciously) think we are. Or hope we might be.

The funny thing about the science of psychology – and I should know, having spent much of my childhood in a psych lab with my father, a developmental psychologist himself, and later conducting experiments of my own – is that we quietly assume our findings represent behavioural ubiquity. We assume, in other words, that some deep root of what we might find in our data should, on some level or other, represent a cognitive underpinning common to all humanity. But quite a lot of human behaviour, and our understanding of it, is profoundly mediated by culture – and what we call gender is among the slipperiest of all.

Would ancient girlhood have looked the same as ours today? Most assume the Venus of Willendorf must have been a talisman – a fertility goddess, surely, with her huge breasts and bountiful stomach. But some anthropologists are now reconsidering whether many of those little goddess figurines, strewn about Paleolithic Europe, were instead self-portraits, or perhaps even dolls. Call her the Barbie of the Danube.

Some day, scientists will find the small, oddly-long body of a doll in a cave not far from the shore. Most of the paint will be gone – thousands of years will do that – rubbed off by sand and air, her lips nude at last, like a woman who has removed her make-up at the end of a tiring day. Maybe there’ll be an eye, still blue, staring out into nothing. The scientists will hold this thing in their hands. They’ll have endless debates. They’ll try to discern what it means – about our children, about our lives. And what will they think of Barbie then? Will they, too, assume she must have been a god?

Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution (Penguin, £12.99) by Cat Bohannon is out now; Barbie is at the Design Museum, London W8

Yahoo News

Yahoo News