Glasgow School of Art fire also destroyed the city's only surviving 'panorama' building – 19th-century virtual reality

The word “panorama” has been used to describe everything from investigative television programmes to wide-angle digital camera settings and movie formats, but when the medium was invented at the end of the 18th century, it set up a new relationship between the viewer and the world.

Back then the word – a fusion of two Greek words meaning “all-seeing” – was coined for a new form of artwork that offered a 360-degree view of a scene. These paintings, invented by Scotsman Robert Barker, plunged the visitor into an unprecedented immersive state of virtual reality and offered them mastery over all they surveyed.

Researching this topic involves detective work, since very few 19th-century panorama paintings survive. We also never know when surviving evidence may be lost. Another victim of last month’s terrible fire at the Glasgow School of Art – the second in four years – was the O2 music venue next door. This huge copper-domed structure facing out on to Sauchiehall Street – now gutted by fire – had a long history as a visitor attraction, including originally as a venue for panorama displays.

How did they work?

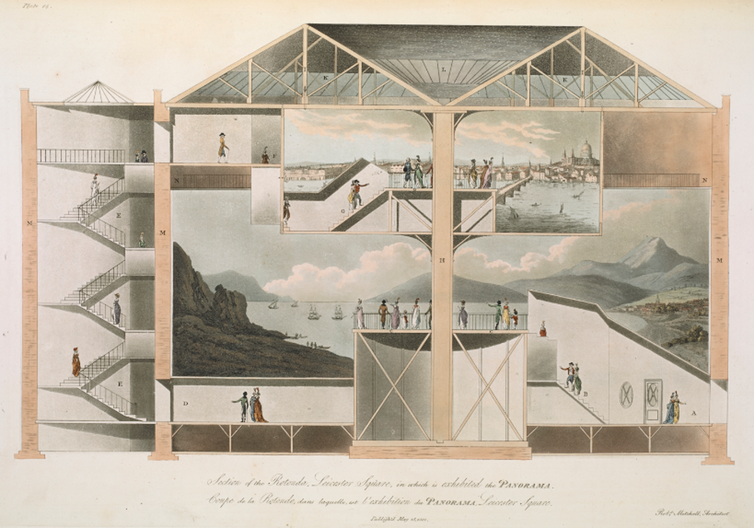

Panoramas began in Britain as huge cylindrical paintings, displayed in purpose-built rotundas complete with a central viewing platform to keep visitors at a distance from the canvas and prevent them seeing past its edges. They also diversified into more transportable forms, such as the “moving panorama” scrolls and light-effect dioramas displayed in the Sauchiehall Street building.

Even the original 360-degree form sometimes went on tour across Europe and North America. I have been examining a surviving set of panorama programmes in the University of Glasgow library’s Special Collections – the booklets that helped visitors make sense of what they were looking at. One title page tells us that the painting was originally displayed at the Strand in London, but the visitor has crossed that out and replaced it with “Glasgow”. One reason why the paintings themselves are lost to us is that their huge hanging canvases were displayed and transported until they fell to pieces.

History in panorama form

What fascinates me about panoramas is their subject matter and how they were received. Some depicted exotic or colonial landscapes, making viewers feel they had travelled to the Arctic or Australia. Others showed recent historical events: the Battle of Waterloo was a particular favourite. Panoramas were not just a leisure activity, they were also propaganda for the British Empire. They played an ideological role in the process of assimilating memory into history.

Panoramas are immersive, making the viewer feel like they’ve stepped on to another continent or into the middle of a battle. They also create a reassuring sense of overview that places the viewer at the centre of the “action”. This was certainly the effect that one battle panorama had on the retired Duke of Wellington in the 1840s, who when he saw one, reportedly “chafed against the barriers like a war horse” and looked like he was commanding the troops all over again. This simultaneous combination of immersion and distance led some to criticise such panoramas as voyeuristic and warmongering.

The influence between panoramas and historical representation worked both ways. Panoramas represented recent historical events, but 19th-century historians writing about recent events also adopted a panoramic perspective. Writing contemporaneous history is difficult because we lack the hindsight to come to authoritative conclusions. In the heyday of panoramas, some historians dealt with their lack of chronological perspective by imagining themselves instead at a spatial distance. Taking to the skies in a flight of imagination, they constructed panoramas in prose.

For example, when Scottish journalist and self-styled Old Testament prophet Thomas Carlyle decided to write an epic history of the recent French Revolution, he struggled to balance intimate portraits of the French king, Louis XVI, and the revolutionary leader Robespierre in his aim to represent the 25m unwitting victims of political upheaval.

He turned to panoramic perspective to help, imagining that if he could take a supernatural flight over Paris, “waving open all roofs and privacies, [and] look down from the Tower of Notre Dame”, he could understand and depict ordinary people’s reactions, from fear to defiance to “dulness calmly snoring”.

One of his contemporaries, the rationalist Harriet Martineau, took up Carlyle’s motif in her sociological journalism. In an article on the pioneering 1851 census, she related how “every housetop in the kingdom was taken off, and every inmate portrayed, in his or her mental and bodily state”. For these writers, panoramic perspective was a way to claim an overview over recent and contentious history.

Along with the recent news that Glasgow School of Art’s Mackintosh Building will have to be demolished, we also lose another link to the panorama era. But our fragmentary knowledge at least helps us understand how they expanded people’s limited vision of the world in the 19th century.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Helen Kingstone does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News