‘It is going to be very, very difficult’: Liberated Kharkiv braces for winter of war

The bodies from the massacre came in black plastic bags, 23 of them laid out in neat rows, victims of an attack on a convoy by Russian forces. The smaller ones were of the 13 children who had been killed in the shelling.

A pregnant woman and two elderly couples were also among those who died on a route leading out of Kupyansk. Some had been burned to death in their cars; others had attempted to crawl to safety on the road, but had not survived their horrific injuries.

The bodies were discovered almost a week after the attack and brought to Kharkiv. Days earlier another 30 civilians, also including children, were killed and more than two-dozen injured in a missile strike while they were leaving Zaporizhzhia, in an area where there were no obvious military targets.

The toll of lives is regarded as a tragic human cost of success – the result of the Russians lashing out after a series of severe setbacks in the battlefield that have led to the fall of their major military strongholds and transport hubs such as Izyum, Kupyansk and Lyman.

Vladimir Putin has reacted to the defeats by announcing the partial mobilisation of 300,000 in Russia and calling hasty referenda followed by annexations in the four Ukrainian regions of Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaphorizhzhia. He has warned that any attempt to take back the annexed territory would be considered an attack on Russia, leading to dire consequences, raising the prospect of possible nuclear strikes.

But while the Russian president proclaims the creation of “Novoroussia”, his forces, for the first time since the retreat from Kyiv at the start of the invasion, are now on the back foot on two front lines.

A Ukrainian offensive in the south has captured a number of settlements and moved more than 25 miles forward, driving back Russian troops who had been redeployed from around Kharkiv to defend Kherson.

As the Kremlin moved its forces, the Ukrainians struck through the Kharkiv oblast and into Donbas, taking cities, towns and dozens of villages in a sweep covering 1,000 square miles.

There was a real possibility just two months ago that the whole of the Donbas would fall under Russian control. With the recapture of Lyman, the direction of the battle in this territory has changed dramatically. Kyiv is now in a position to claw back more land in Donetsk and Luhansk, moving closer to the two separatist republics before winter sets in.

Lyman, on the bank of the Siverskyi Donets river, is a major rail hub and its loss means the Russians will have difficulty keeping supplies flowing into the town of Svatove, where they have pulled back troops who have not been captured or surrendered.

The Russians captured the cities of Severodonetsk and Lysychansk at the end of May, with Bakhmut predicted the next to fall. The two main cities of Ukrainian-held Donbas, Slovyansk and provincial capital Kramatorsk, were also at risk. More than 100 Ukrainian soldiers were dying every day in what appeared to be a losing struggle.

The arrival of Western weaponry, especially Himars (High Mobility Artillery Rocket System) and MLRSs (Multiple Launch Rocket Systems) began to swing the balance. Bakhmut remains standing, seeing off fierce Russian assaults, and the capture of Lyman has meant Slovyansk and Kramatorsk are more secure, leading to a recent drift-back of people who had left.

The backlash from the fall of Lyman, just 24 hours after celebrations of the annexation in Moscow, has been unlike any previous loss suffered by the Kremlin.

Ramzan Kadyrov, the Moscow-backed Chechen leader whose fighters have been extensively deployed in Ukraine and have suffered large-scale casualties, accused the military command of “covering up” for an “incompetent” general who should be “sent to the front to wash his shame with blood”. He called for “more drastic measures”, including the use of “low-yield nuclear weapons”.

Yevgeny Prigozhin, the oligarch who is a staunch Putin ally and runs the mercenary Wagner Group, issued a statement supporting Mr Kadyrov, saying: “Send all these pieces of garbage barefoot with machine guns straight to the front.” However, his own men from Wagner are performing poorly in Bakhmut.

Yevgeny Primakov, the son of the former prime minister and head of the government-run Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States, pointed out on Telegram: “We have given a Russian city to the enemy for the first time since the Second World War.”

Unsurprisingly, the mood among the Ukrainian military is exultant. “We are feeling very confident,” said Nicolai, a captain in an artillery unit. “The Russians fought hard at the beginning, but are now giving up rather than fighting; they have decided they don’t want to die, so we have a huge number of prisoners.

“The ones who really fought were small in numbers. A lot of the others are from the DNR and LNR [the Donetsk and Luhansk separatist republics]; they are badly armed and badly trained. The ones who come from Russia are better, but not much better – they look in bad shape.”

Nicolai, who had taken part in the operations to capture Izyum before Lyman, continued: “The Russians shelled the bridges across the river. We put up pontoon bridges and used boats to get around that; a lot of the operations were at night. We surprised them many times.”

But there are still Russian units in the area. Nicolai’s comrade Serhiy, a lieutenant, was injured when Kupyansk was attacked from an area thought to have been cleared.

“It was nothing much, a bit of metal flying. We were in the open and they used the trees as cover,” he said, raising his right hand, covered by a bloodstained bandage. “Our perimeter lines have moved further; we are better prepared now. If they send these people they are mobilising, they will be killed. They haven’t got enough time to train them for these kinds of conditions.”

Both the soldiers were quick to praise the effectiveness of Western arms. “Send us more Himars, more MLRSs,” said Serhiy. “Boris Johnson was so good in supporting us; I hope the UK continues that support with the new leader. We are very grateful to all our friends.”

The warning by Mr Putin about the consequences of attacking the new “Russian” territories was dismissed by Nicolai and Serhiy. “These are empty words of someone who’s losing; we need to keep going forward, we need to keep our momentum,” Nicolai stressed.

What about the threat of using nuclear weapons? “No, that is not going to happen,” said Nicolai. “The Americans, Nato will destroy the Russians in that case. Putin is not completely mad.” Serhiy looked at his friend and raised an eyebrow. “Are you really sure he hasn’t gone mad?” he asked. “Some of the Russians we’ve taken think he has, don’t they?”

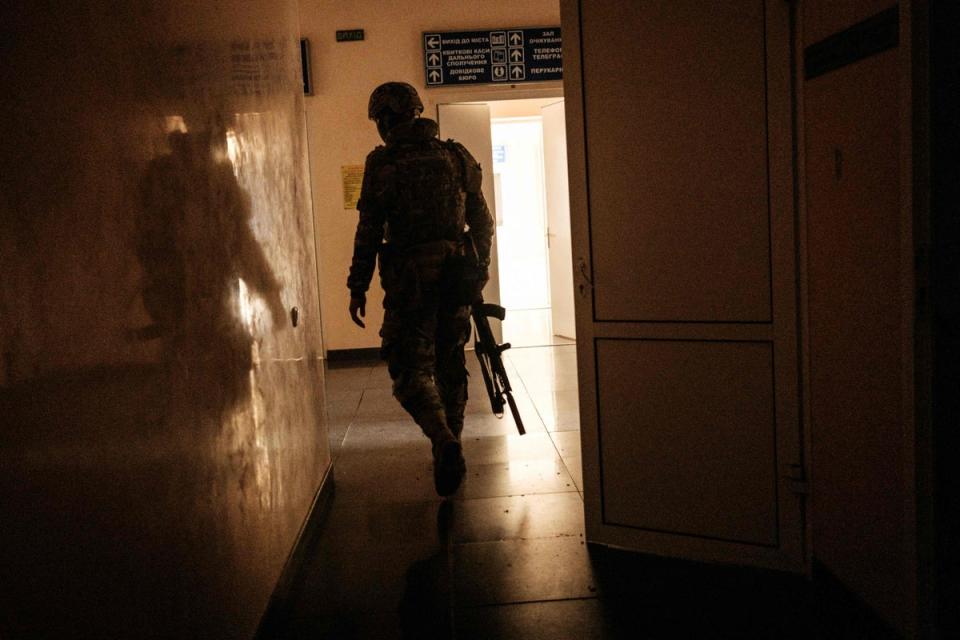

Conventional weaponry has been enough to cause devastating damage to Kharkiv with artillery rounds and missiles since the start of the war. Ukrainian forces heading out of the city drive past row after row of damaged and destroyed buildings, and smashed Russian tanks that are kept on the roads as a reminder of just how close the enemy came to capturing Ukraine’s second city.

Watching them, 39-year-old Anastasia Bondarenka spoke of what had happened to her in Saltivka, the most heavily shelled suburb of Kharkiv, which is now almost deserted apart from a few families hanging on.

“The first bombs killed my mother – she was 78 years old; that was in March. A cousin lost a leg outside a shop three weeks later. I lived in a metro station with my children for the next four months. Now there are seven of us living in one small apartment of a relative,” she said.

“We have winter coming, with power cuts. We’ll probably have no heating. It is going to be very, very difficult. I don’t know how we’ll cope. I think a lot of people will die.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News