The Guardian view on Tory leadership and the constitution: a crisis in the making

For a country that takes pride in the venerable stability of its democracy, Britain is strangely prone to constitutional improvisations. For example, if the current Conservative party leadership contest proceeds as far as a ballot of party members, it will be the first time a prime minister is chosen by that method.

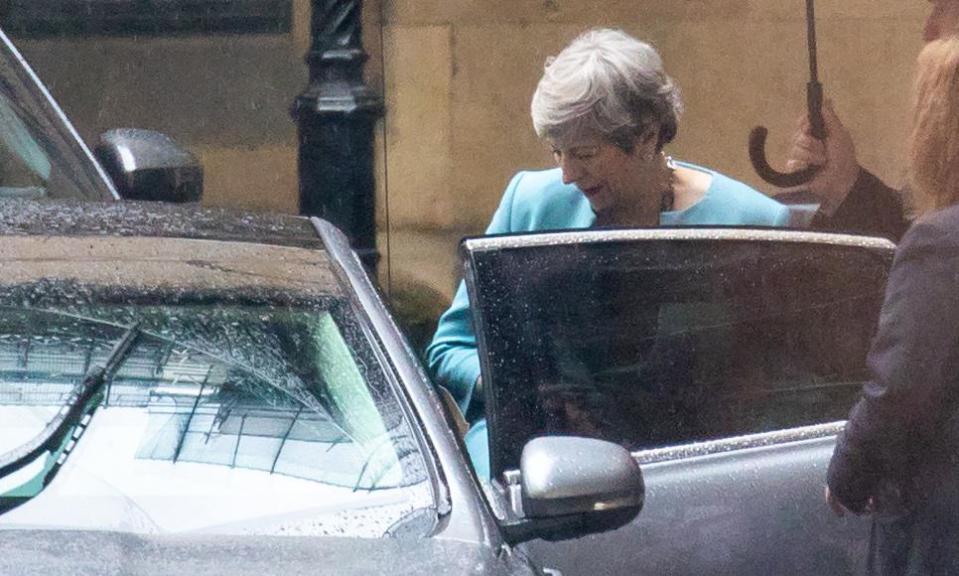

In 2016, Theresa May’s rivals withdrew before the final round. In previous applications of the rules it was the leader of the opposition being chosen, not a head of government. The system itself only dates back to 1998. Fine-tuning of the rules was completed by the 1922 Committee just three weeks ago. The process looks undemocratic and has no basis in ancient precedent.

The antique aspect is the Tories’ sense of entitlement to power. The Conservative party has been around so long as to have become intertwined with ideas of established authority, constitutional order and the natural way of doing things – at least in the imaginations of many Tories. But there is no reason for others to indulge that cultural conflation of party and state.

The only sign that Conservatives are embarrassed by their exorbitant privilege in appointing the next prime minister is the decision to hold televised hustings, parading candidates before a wider public in a simulation of accountability. But the debate format exposed the perversity of the whole affair. It mimicked a general election but without the element of universal suffrage. Perhaps the broadcasts influenced MPs’ decisions, but the elimination of Rory Stewart from the third round on Wednesday evening suggests that they are not overly concerned with the opinions of non-Tories, towards whom Mr Stewart’s candidacy was most effectively geared.

It defies principles of democratic representation that 160,000 Conservative members, a cohort that is much richer, older and whiter than the general population, should impose their choice on the rest. There would be equivalent problems if Labour had a leadership contest while in power. There is an awkward tension between rulebooks written to enhance internal party democracy and the logic of a parliamentary democracy that locates a prime minister’s mandate in the Commons, with MPs as the channel for transmitting the popular will.

This problem has turned acute for three reasons. First, the keys to Downing Street are changing hands in a hung parliament. Theresa May’s mandate is flimsy enough before being passed on to a successor. Second, parliament’s authority has been sabotaged by the 2016 referendum – an ill-conceived experiment in direct democracy that landed a ferociously complex task in the lap of a reluctant representative chamber. Third, the Fixed-term Parliaments Act limits the prospects for an early election, the traditional pressure valve when governments cease to function.

To appoint a prime minister without a credible national mandate would be awkward in less volatile times. To do it three months before Britain’s EU membership expires, when half of the country might prefer not to leave, places immense strain on the legitimacy of the system. And to put the responsibility for managing that risk in the hands of someone as divisive and provocative as Boris Johnson threatens a full-blown crisis. It will certainly increase the pressure for a general election. If enough moderate Tories withhold support from a Johnson-led administration (as some have said they would, should a no-deal Brexit be on the agenda), he might not command a majority in the Commons. It is a grave decision for the crown to appoint a prime minister if it is uncertain that such a key requirement is met.

These are not abstract issues. British politics functions by a complex operation of law, protocol, convention, precedent, habit and uncodified norms of decent conduct. Brexit has thrown the whole edifice off kilter, imperilling a delicate balance that sustains British democracy. The Tory leadership contest is being properly conducted, to the extent that the rules are being followed. But it is being held without adequate regard for the wider electorate; and without regard for what is at stake if the ultimate winner radiates contempt for the millions who have no say in his election.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News