Hannibal Lecter without the charm: Brian Cox on becoming ‘truly evil’ in Manhunter

How different modern cinema might have been if Hannibal Lecter had sung I Just Called to Say I Love You down the phone. The now-unlikely scenario was almost included in the original Lecter film – Michael Mann’s 1986 thriller, Manhunter – as Hannibal, then played by Brian Cox, calls the FBI profiler who put him behind bars (and Plexiglass).

“I had the line ‘I just called’ and when we filmed it I immediately went off doing Stevie Wonder,” recalled Brian Cox in a 2016 interview. “Of course, Michael [Mann] loved this. He thought this was tremendous, Hannibal Lecter singing Stevie Wonder to his arch-nemesis. It was in the film for a while but I think they had problems with rights. Well, I think they had problems with association… the Stevie Wonder people probably didn’t like the idea that I was going to be singing this song with a kind of twisted attitude towards it.”

Thirty years since The Silence of the Lambs made Hannibal Lecter a franchise-spinning mass-appeal (and murdering) monster, Manhunter remains an anomaly in the Lecter canon – even without the Stevie Wonder rendition.

Based on Thomas Harris’s novel Red Dragon, it’s a vivid, waking nightmare in which the psyches of its three principal characters – FBI profiler Will Graham (William Petersen), serial killer ‘The Tooth Fairy’ (Tom Noonan), and, of course, Hannibal himself – bleed into the world they inhabit. One critic described it as “designer-expressionist”, with its modernist Eighties-ness, thumping synth soundtrack, and palette of stark, psychological states – deep hues superbly created by Italian cinematographer Dante Spinotti.

Watched now, Manhunter far exceeds the dismal response it received in 1986. It’s also fascinating in its difference to The Silence of the Lambs and other adaptations of Thomas Harris’s books; most obviously, in the contrast between the two Lecters: the performative villainy of Anthony Hopkins and cold disdain of Brian Cox.

“People were very nice about the performance,” Cox tells me . “And the subsequent debate between Tony and myself. Which is always funny. We've worked together but we never discuss it.”

First published in 1981, Thomas Harris’s Red Dragon is a taut, psychological procedural. Michael Mann described it as “the best detective story I’ve ever read”. In the story, Will Graham is dragged out of retirement to catch ‘The Tooth Fairy’ – AKA Francis Dolarhyde – a serial killer nicknamed for biting victims with a deformed set of dentures. So far, he has slaughtered two idyllic families.

Graham has a special ability to put himself in the minds of killers, and carries mental – and physical – scars from previous cases. But he must confront his biggest demon – the murderous psychiatrist Dr. Hannibal Lecter – to help profile the Tooth Fairy.

Italian producer Dino de Laurentiis bought the rights to the book and hired Michael Mann to write and direct. When researching the script, Mann met and corresponded with murderer Dennis Wayne Wallace, who killed several people to “save” a woman with whom he’d become obsessed. Wallace believed that In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida by Iron Butterfly was “their song”; Mann would use the 17-minute epic in the climax of Manhunter.

Mann also observed a conflict in Wallace’s story: as an abused child, Wallace was a victim; as an adult, he was responsible for heinous crimes (“Both are true” Mann later said about Wallace). Duality became a powerful theme in Manhunter: by putting himself in the minds of killers, Will Graham walks a line between alternate mental states. Hannibal acts as Graham’s darker half. “The reason you caught me, Will, is we’re just alike,” Hannibal tells him. Elsewhere, the Tooth Fairy is conflicted over murderous fantasy and relative normalcy when he falls for a blind colleague (played by Joan Allen).

For the role of Lecter – strangely respelled ‘Lecktor’ in Manhunter – Michael Mann considered various names, including John Lithgow, Mandy Patinkin, and – rather bizarrely – the director William Friedkin. Mann’s number one choice, Brian Dennehy, recommended Brian Cox, who was starring in a play at the New York Public Theater.

Casting director Bonnie Timmermann went to see the play and filmed an audition with Cox the very next day. “She asked me if I would turn away from her when I did my audition,” says Cox. “I thought odd, but did the scene turned away. When it was over, I asked her why and she said, 'I was late when I got to the theatre and I couldn't get to my seat, so I didn't see you in the beginning. I heard you and it was your voice I really liked, and that’s what I want Michael to focus on before seeing you.’”

Cox admits to always being “fascinated” by serial killers, and took inspiration from Scottish murderer Peter Manuel, Ted Bundy, and the idea that evil is "the absence of empathy" – an observation made by the Nuremberg Trial psychologist Captain G. M. Gilbert.

“No empathy,” says Cox. “That evil is without empathy or any sense of consequence outside of how it serves himself. Clearly, Hannibal had this essence.”

Later, Hopkins' version inspired a cycle of sharp-minded, gimmicky serial killers – usually the mark of a horror film that wanted to be taken seriously, most notably Se7en.

“There is a fantasy element to Lecter,” says Daniel O’Brien, film lecturer and author of The Hannibal Files. “Supposedly, real-life serial killers have said that if they’d been as articulate, intelligent, and engaging as Lecter they wouldn’t have become serial killers – because they wouldn’t have needed to fill whatever dark void there was by taking other people’s lives. He’s as much drawn from an adult Grimms’ fairy tale as he is drawn from reality.”

William Petersen got very real for the role of Will Graham. He spent time with the FBI at Quantico, where the FBI Academy is based, and with the Chicago Police Department’s violent crimes unit. After six weeks, Mann asked Petersen to stop; he didn’t want the actor to become desensitised to the crimes.

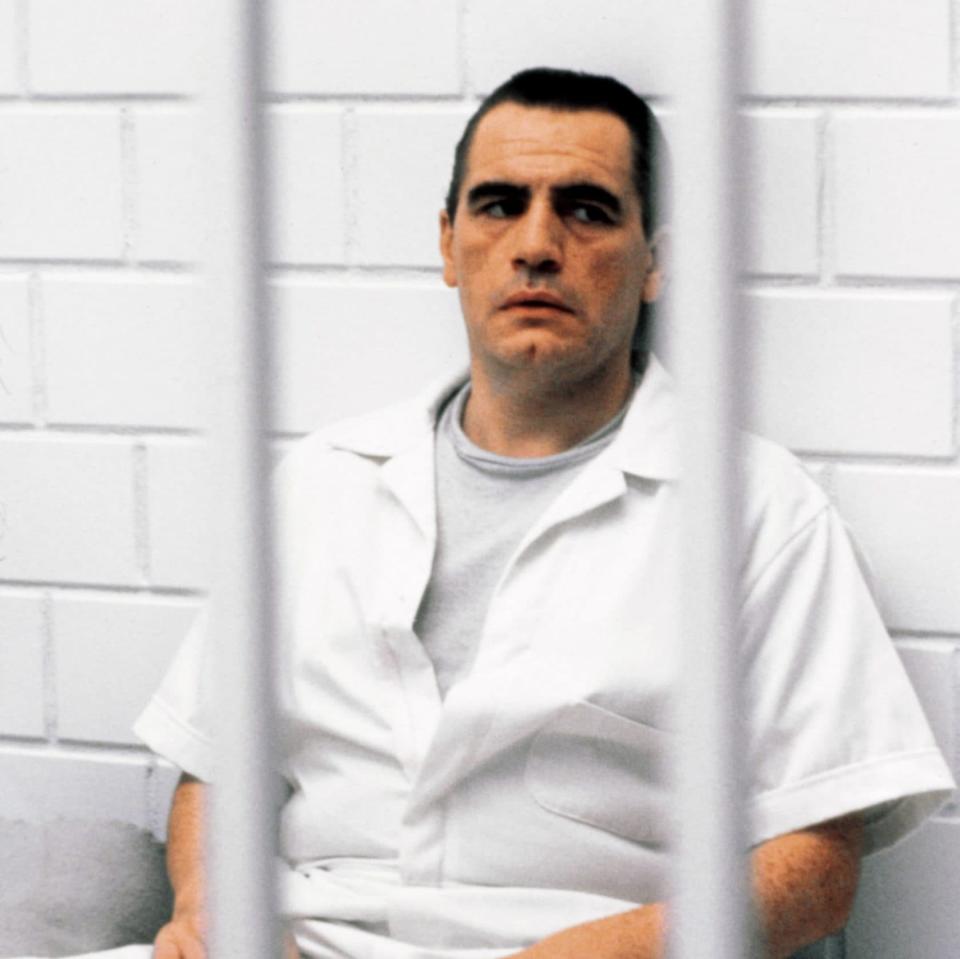

The psychological power of Manhunter – and its place in the wider Lecter canon – is captured early in the film, with the meeting of Graham and Hannibal, who is incarcerated in a pristine white maximum security cell. The effect was achieved by beaming a powerful bank of lights onto Cox. “Bright lights,” he says. “I could hardly see Billy [William Petersen]. Very sterile.”

The scene is appropriately clinical – a game of mental chess in which Hannibal picks at Graham’s damaged mind. It was rehearsed extensively and took three days to shoot (Cox recalls rehearsing in a house in Wilmington, North Carolina: “It was a house on stilts and there were alligators crawling underneath. I thought it was quite appropriate”).

Cox has described how he approached the scene in different ways – “broader... louder... more forceful... more violent” – and the result is almost precision-perfect in its execution.

This Lecter is cold, calculating, and bored. He’s capable of black humour (“I wouldn’t want them to think I’m dwelling on anything morbid,” he says about his doctors) and constructs a phony cordiality. “Would you like to leave me your home phone number?” he asks Graham – part mocking, part threatening his old nemesis.

If Anthony Hopkins’ cultured cannibal is curious and playful, Cox’s version has barely-concealed contempt. “His Lecter is not out to impress,” says Daniel O’Brien. “Why would he want to impress people he despises? He regards most of the human race as no more significant than ants.”

Cox says that he and Michael Mann were on the same page about how to bring Hannibal to life. “The psychology is what was fascinating,” he says. “Both Michael and I wanted him to come across as truly, truly evil so that the audience would feel it even in the most mundane gestures. And that is where we succeeded.”

Most of the other Lecter adaptations include a version of this scene, each example speaking to a different creative mindset and context. In The Silence of the Lambs, essentially a retread of the Red Dragon story, the equivalent moment, the iconic meeting with Lecter (Hopkins) and Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster), is pure horror – Lecter is now a monster locked in a literal dungeon.

In 2002’s Red Dragon, it becomes, like the rest of the film, a perfunctory remake of Manhunter, but in the image of The Silence of the Lambs; and in the TV series Hannibal, which covers the events of Red Dragon in its third season, it’s reimagined within the mind of Lecter himself (now played by Mads Mikkelsen), playing out like a therapy session with Graham (Hugh Dancy) – a taster of the series’ deep, sometimes-ludicrous delve into the psychology of pop culture’s favourite cannibal.

Back in Manhunter, the real monster is Tom Noonan’s Francis Dollarhyde (‘Dolarhyde’ in the book). Born with a cleft lip and palate, he believes himself to be disfigured; by murdering people – or “changing” them – he transforms into a persona called the “Red Dragon”, inspired by the William Blake painting, which – in the book and other versions – he has tattooed across his body. Scenes were filmed with Noonan sporting the tattoos, but Mann scrapped them. “Michael Mann felt they were too much,” says Daniel O’Brien. “It was veering towards ludicrous.”

Michael Mann also cut the character’s abusive childhood, making him less of a tragic, out-of-control figure (see Ralph Fiennes damaged man-child version in Red Dragon). Noonan’s killer is more purposeful. And as far as serial killers go, he has an incredible taste in chic Eighties futurist décor – check out his purpose built house, described by Dante Spinotti as “American new modernism” – and line in flashy shirts. The psyche becomes the environment.

“You get the sense that however demented he may be – which is considerably – he’s in control of what he’s doing,” says O’Brien. “He has an ordered life. He says to Freddy Lounds [a tabloid journalist who Dolarhyde kidnaps tortures], ‘You are witnessing a great becoming’. He breathes his own psychopathic mind.”

Speaking on the DVD extras, Noonan explained how he got his feel for the character during the audition. “They put this woman with me to read,” Noonan said. “She seemed really frightened. As she started to feel frightened, I started to feel this power.” During production, Noonan requested that people address him as “Francis” and that he didn’t see the actors whose characters he was pursuing, or were in pursuit of him. “It created this atmosphere on-set where people were frightened of me,” said Noonan. He also travelled on different airlines and stayed in different hotels. The first time Noonan saw William Petersen was when Petersen’s hero came crashing through Dollarhyde’s window for the climatic shootout.

“On the last night when we shot the climax, we worked all night long with him and I didn’t talk to him in between takes,” said Petersen, also speaking on the DVD. “And when it was all over, he and I went out for breakfast.”

Originally, Michael Mann had intended to keep the Red Dragon title, but Dino de Laurentiis insisted they change it – apparently to distance the film from box office flop The Year of the Dragon, which de Laurentiis had also produced. Michael Mann argued with de Laurentiis about the title change, and Brian Cox branded the Manhunter title “cheesy”.

Released on August 15, 1986, it only made $8.62 million at the US box office. It wasn’t released in the UK until 1989. Dino de Laurentiis’s deal gave him the option on future Thomas Harris books, but he passed on The Silence of the Lambs. He returned – no doubt inspired by Lambs’ $273 million box office and five Oscars – to produce the subsequent films in the series: Hannibal, Red Dragon, and Hannibal Rising.

After Manhunter, William Petersen found he had gone too deep into the fractured mind of Will Graham. “Ultimately, it had creeped in,” Petersen said. He struggled to rehearse a new character. “He was always coming out Will Graham,” said Petersen. “One day I woke up and said, ‘I can’t get rid of this guy’. I went into a hairdresser and had them dye my hair blond just so I would look in the mirror and see a different person.”

Brian Cox, meanwhile, has always seemed content with his role being popularised by Anthony Hopkins. “The only thing I regret is the money,” he later said.

Speaking about Manhunter in 2017, Brian Cox described how he was inspired by Ted Bundy’s persona – a “construct” of his true self. That is, ironically, what Hannibal Lecter became after The Silence of the Lambs. In Hannibal, he’s an anti-hero – disemboweling an untrustworthy cop and feeding a monstrous paedophile to the pigs. In Red Dragon, he’s an exaggerated cash-in on his own success. And in Hannibal Rising – an unnecessary prequel about his childhood – he feels like a straight-to-DVD B-movie player.

In Manhunter, he’s largely unknowable; he isn't yet 'Hannibal the Cannibal'. “He’s presented as his monster, this ogre, but we really don’t know where he came from,” says O’Brien. “It’s not supernatural but he’s something beyond human comprehension. You don’t need graphic depictions of face chewing or skinning. There’s enough in Cox’s performance.”

As Brian Cox himself describes, it’s the “insidious nature” of not knowing what Hannibal is thinking. “I felt, and still very much feel, what made Hannibal so menacing was the mystery of who he was,” says Cox. “Later on he lost his mystery and became iconic. And that is not to take away from Tony's performance, which I think is marvellous.”

As Cox has previously said, Manhunter is horror implied. “Everything is suggested. All auto-suggestion,” he says. “That's what Hannibal does. He auto-suggests. And that's what makes his insidiousness timeless.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News