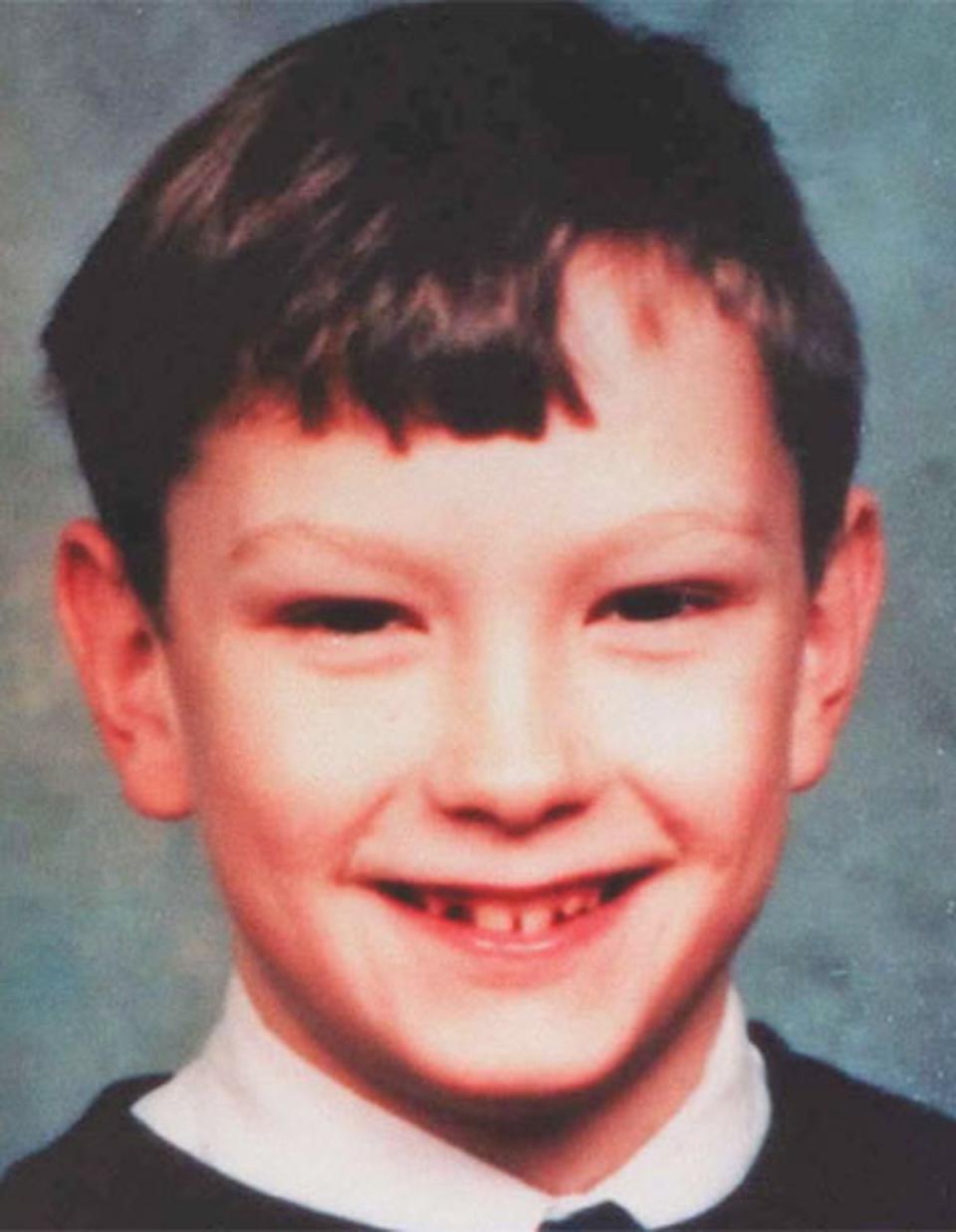

What happened to James Bulger? The disturbing child murder and its troubled aftermath

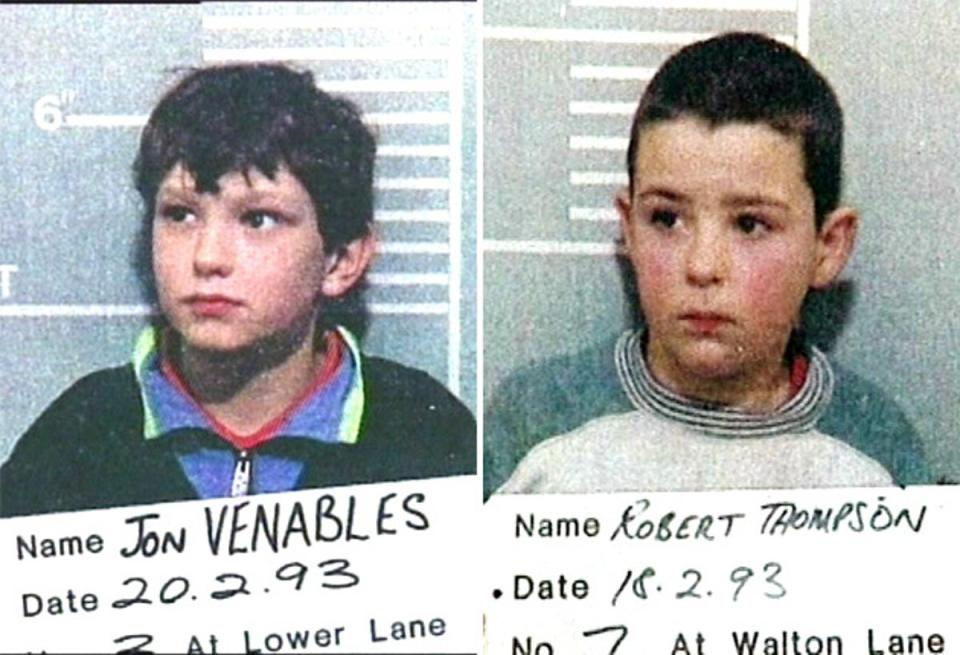

Jon Venables, one of two primary school pupils convicted over the abduction and murder of toddler James Bulger 30 years ago, is taking part in a parole hearing that could grant him his freedom.

Venables was jailed alongside accomplice Robert Thompson on 24 November 1993, in one of the most notorious crimes in British history. Both boys, aged 11 at the time, were released under new identities in June 2001.

While Thompson has rarely been heard from since, Venables was arrested for affray and cocaine possession in late 2008. He was recalled to prison in March 2010 when images of child abuse were discovered on his personal computer. He was released in July 2013 only to be recalled again in November 2017 for the same offence. He was most recently given a parole review in September 2020 that ended in rejection.

Bulger’s family will not be allowed to attend this week’s closed-door hearings but their victim impact statements will be read aloud and taken into consideration during the two-day session on Tuesday and Wednesday.

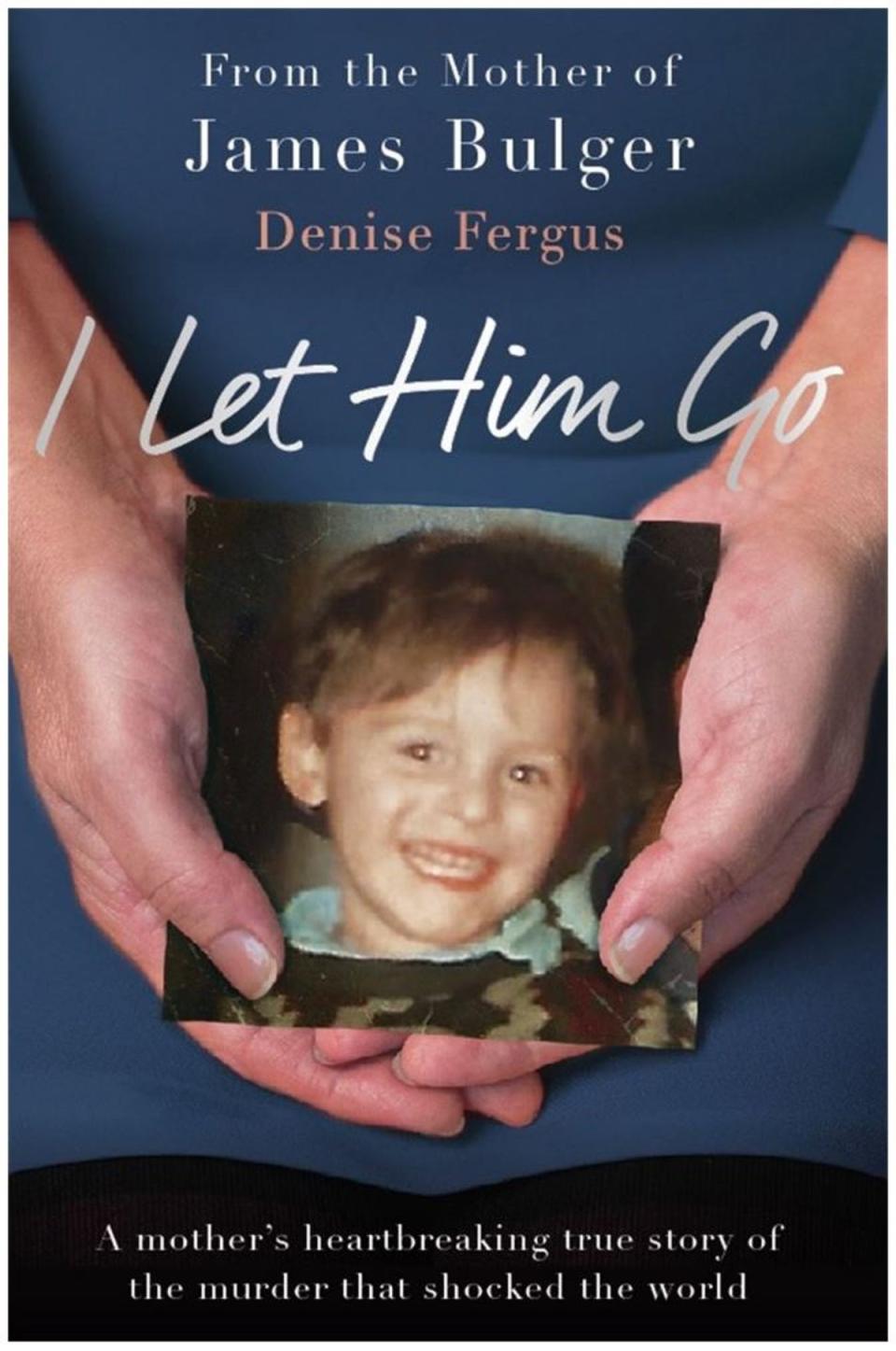

In an interview with The Mirror on Sunday, James’ mother Denise Bulger was asked whether she hoped Venables would be kept behind bars.

“I have to have hope,” she replied. “I believe parole bosses will see what this man is capable of, what he could inflict on society. “If his parole is rejected, we will rejoice. It’s been such a long journey. James deserves that justice.”

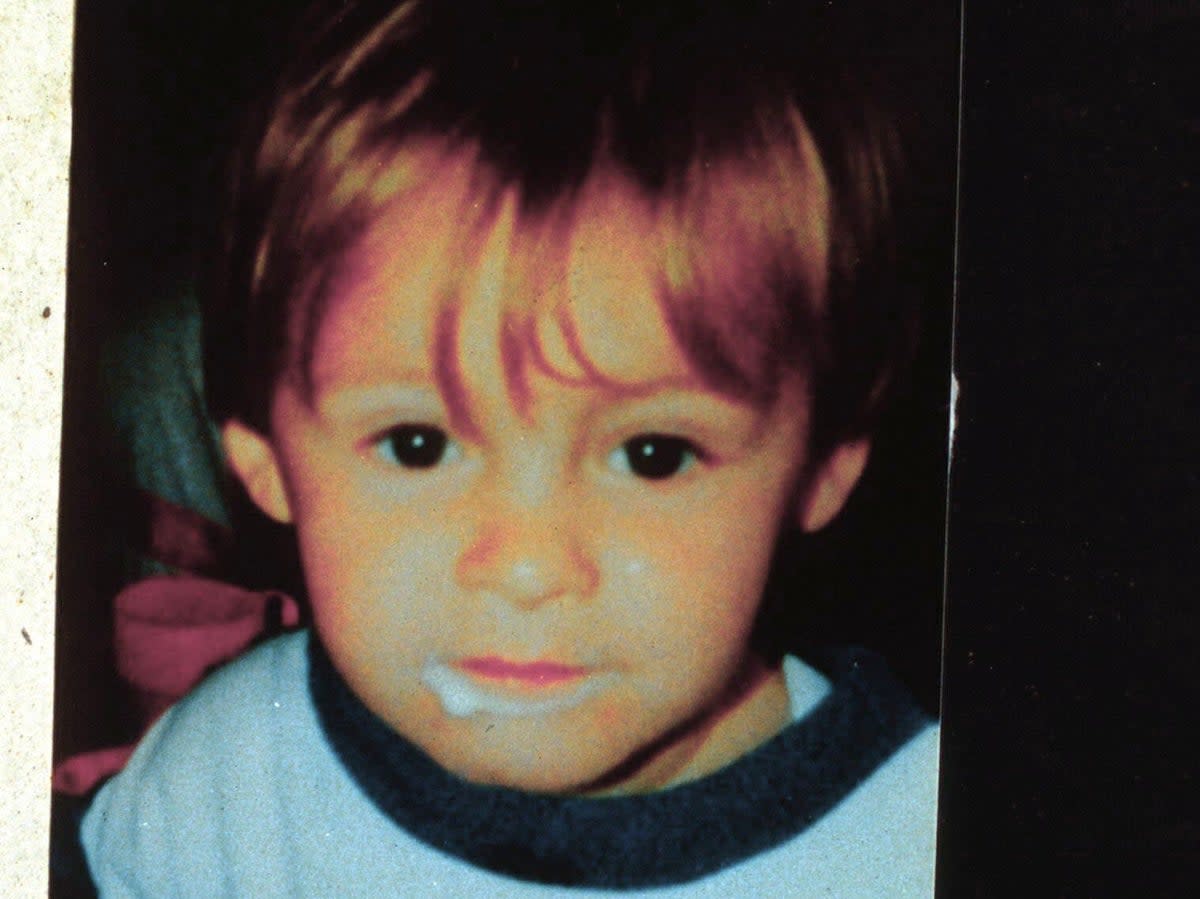

On the last day of his young life, two-year-old James been out with his mother at the Strand shopping centre, in Bootle, Merseyside.

As she placed an order at a butcher’s shop, she believed James was by her side when she was being served – but when she looked down, he was gone, as the subsequent murder trial at Preston Crown Court heard.

Two minutes later, school truants Venables and Thompson were captured on CCTV leading her son away, hand in hand.

“We see James being led away by the two killers,” David Wilson, emeritus professor of criminology at Birmingham City University, told The Independent in 2017 as he reviewed the footage. “For all the world it looked like an innocent setting. The fact that there is a visual image about what was going to happen to that little boy, I think, was the beginning of allowing that crime to seep into our consciousness in a way that other crimes did not.”

Meandering across Liverpool, the boys were seen by 38 people, subsequently dubbed “the Liverpool 38” by the tabloids. Most assumed James was Venables and Thompson’s younger brother. A couple of people challenged them but the boys assured their inquisitors they were taking James to a nearby police station.

“There is a community or public witnessing of what was happening and being disquieted about it, but for various reasons not being able to prevent what was about to happen,” Professor Wilson recalled.

Venables and Thompson betrayed only one moment of hesitation, when they faced the Walton Lane police station, but quickly continued on their way, leading the toddler up a steep bank towards a railway line.

There, the boys threw blue modelling paint, which they had earlier stolen, into James’s left eye. They kicked and stamped on him, threw bricks and stones at him and placed batteries in his mouth. Finally, they dropped a 22lb iron bar onto the toddler’s head, causing 10 skull fractures. Then they laid him across the railway tracks, weighing his head down with rubble in the hope that his death would appear to be an accident.

Home Office pathologist Dr Alan Williams would later testify that he counted 22 bruises, splits and grazes on James’s face and head and 20 more wounds on his body. He was unable to determine which had been the fatal blow.

In the immediate aftermath of his disappearance, police scoured the area and examined the CCTV footage. When they pinpointed the moment James was taken, they released the still images from it, which would become forever associated with the crime.

Denise and her husband Ralph made an emotional appeal for their son’s return but, two days after his disappearance, the toddler’s body was found, just 200 yards from the police station.

“The biggest thing”, Detective Superintendent Albert Kirkby, who led the investigation, later told The Liverpool Echo, “was having to accept the possibility that the people who had murdered James were going to be very young.

“We thought, from what happened with the body, that it had to be the work of an adult. It was very difficult to get our minds around that potential situation that we could be dealing with two young boys.”

A combination of the footage and various sightings led them to Venables and Thompson.

His colleague Detective Sergeant Phil Roberts told The Powys County Times that Thompson’s brother said they had “just been to lay flowers” at a memorial for James just before Thompson was arrested.

“When I heard that, the first thing I thought was ‘it can’t be him’,” DS Roberts said. “He totally denied everything. He never showed any remorse during any stage of the interview. I understand Venables did.

“He acted whiter-than-white in interview and in many ways he was very clever in a conniving, streetwise sort of way, but in the end he shot himself in the foot by giving me a detailed account of what James Bulger was wearing.

“This is where we thought ‘we’ve got him’ because no 10-year-old would remember what he was wearing in such detail unless they had reason to.”

Officers charged the boys with murder six days after James disappeared.

As The Independent’s Bryan Appleyard reported from South Sefton Magistrates’ Court in Bootle on 22 February that year, violent scenes erupted as huge crowds gathered outside.

“Kill the bastards,” they cried. “A life for a life.” Photographs the next day showed distorted faces, arms flung wide in anguish and fury. “They’ve got to take out their frustration on someone,” a policeman told Appleyard at the scene. “You can understand it.”

The crowds’ fury had been whipped up by tabloid newspapers and politicians. Then-prime minister John Major, for one, had responded to the crime by saying that society needed “to condemn a little more, and understand a little less”.

There would be similar violent scenes outside Preston Crown Court that November, with abuse screamed at the police, press and any passing vans that might contain the defendants.

“Everybody tended to think Thompson was the ringleader, just by looking at him in court,” said the author Blake Morrison, who covered the trial and eventually wrote a book about it called As If. “He seemed much tougher. He stared out journalists, whereas Venables was very emotional and cried. He seemed the weaker. But that was just the perception in an adult court.

“We know that Venables had a temper and had been known to lose control and had done some pretty weird things, so in reality I think it is just as likely that he was the instigator.”

Following the 17-day trial, presiding judge Sir Michael Morland bowed to public pressure and named the boys, who until then had only been known as Boy A and Boy B. He said they were guilty of “unparalleled evil and barbarity”, before ordering their incarceration, with a minimum tariff of eight years.

The “Devil Himself Couldn’t Have Made A Better Job of Two Fiends”, The Sun’s headline read the next day.

“How Do You Feel Now, You Little Bastards?” The Daily Star asked.

A Daily Mirror headline called Venables and Thompson “Freaks of Nature”.

“I think the fact that they were given names made a big difference… If they hadn’t been there just couldn’t be as much to write and speculate on,” said Morrison.

“It is very unusual to have children murdering children so the rarity factor was one thing,” he continued, attempting to explain the public fascination with the case, which endures 30 years on.

“When you have got two people who are involved in a crime, especially two so young, inevitably there is psychological speculation. There is with any murderer, but there is an increased amount of it because you are thinking: ‘Was one of them the ringleader or the other one?’ You wonder how the chemistry between them worked.

“The fact that Thompson and Venables were held back for a year in school because they had August birthdays and they weren’t performing well meant they formed a team together,” Morrison said. “There was resentment of younger siblings in both cases, which made them not people to trust with a small child.”

The case would take a personal toll on Ralph and Denise, who separated the year after the murder, in 1994. Denise would go on to marry electrician Stuart Fergus in 1998. The pair have three children together and she set up the James Bulger Memorial Trust in her murdered son’s name.

Ralph eventually settled with partner Natalie McDermott. They had a baby daughter in 2013.

Blake Morrison has since likened the place held by James Bulger’s killers in the British public’s imagination to that occupied by such ghouls as Peter Sutcliffe, the Moors Murderers and Fred and Rosemary West.

“I don’t think we have learnt a lot,” he said in 2017. “The fact is that at 10, the age of criminal responsibility remains shockingly low, which puts us way out of line with other countries in the world, certainly those in Europe.

“If there was a similar crime today, I’m not sure we’ve learnt enough to deal with the kind of vilification and demonisation, and whether we’ve learnt that children in a courtroom with an international media presence isn’t the right way to go about looking at that crime, drawing the consequences and deciding on treatment.

“There isn’t much reason to feel things have changed or we’ve learnt our lessons or we’ve become better. There are few measures that have been put in place to protect children like appearing on screen, but we haven’t learnt enough.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News