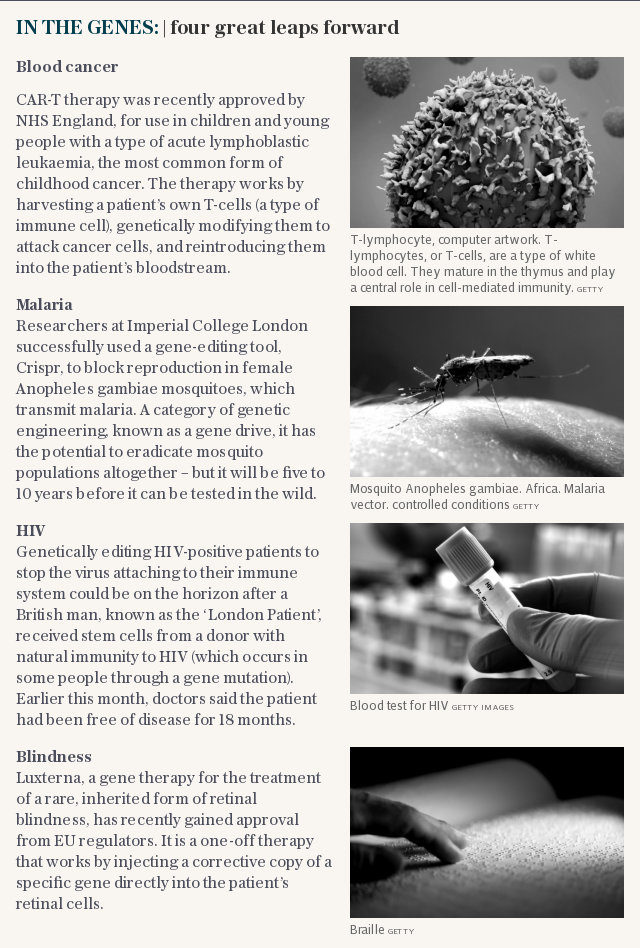

This Harvard scientist wants your DNA to wipe out inherited diseases - should you hand it over?

Imagine a future where an online dating app doesn’t just match you to potential partners who meet your preferences for age, height and fondness for pinot noir, but to those with whom you’re genetically compatible. Not so much people you’re likely to have physical chemistry with – apps that make dubious claims to do that on the basis of a cheek swab already exist – but those with whom you won’t pass on a devastating genetic disease to your children.

It’s not sexy stuff; certainly not first-date conversation. Most people only discover that they’re among the four per cent who carry the same recessive genetic mutation for a rare condition, such as cystic fibrosis or Tay-Sachs, as their partner when their baby is born with it – or dies from it.

True, couples could find out their genes don’t mix after they’ve decided to have a baby and before they start trying – but how heartbreaking would that be, once they’re already in love? Far simpler never to meet in the first place, and simply to pick from the other 96 per cent with whom they can mate with abandon.

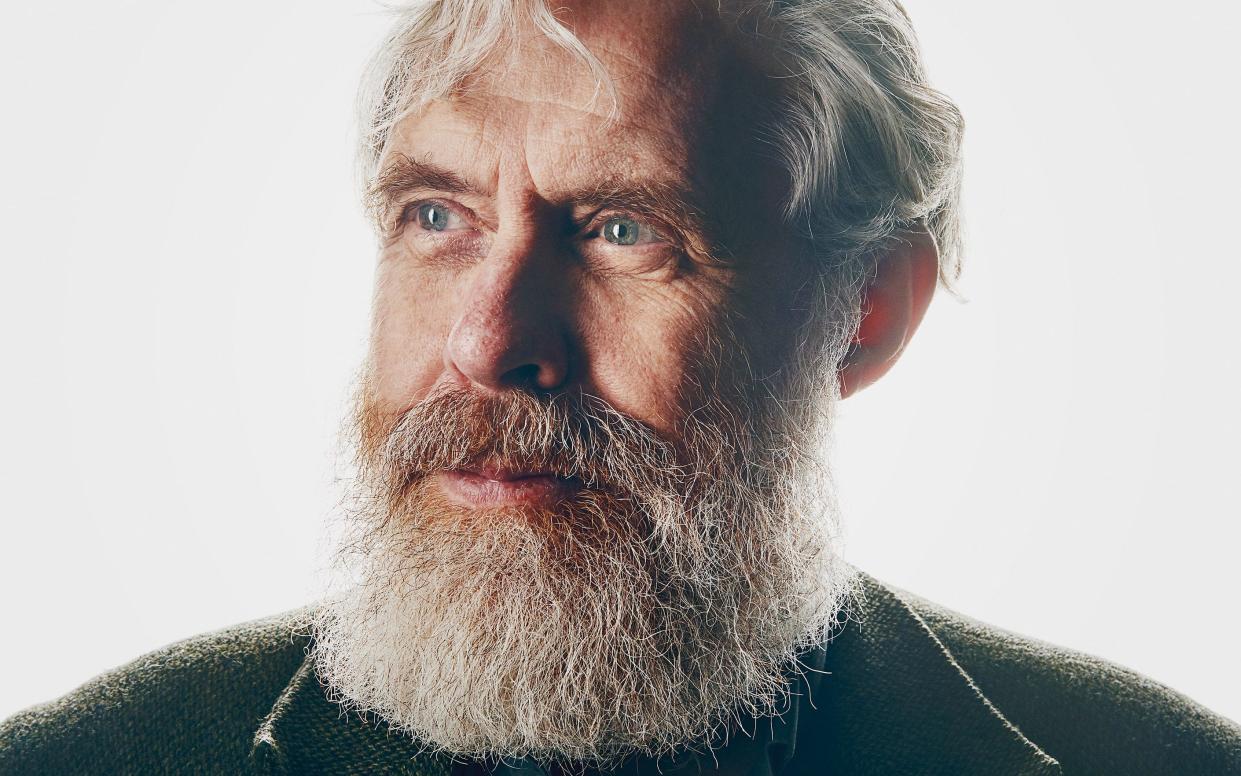

This is the vision of maverick Harvard geneticist Professor George Church. Or rather, it’s one of the least outlandish of his ideas, compared to some of the others he has in the pipeline: genetically modifying pigs to grow organs fit for human transplant; reversing ageing in dogs, as a prelude to doing the same in humans; resurrecting the woolly mammoth. Oh, and rewriting the entire genetic code of human life.

Perhaps little wonder that some have accused him of playing God. ‘How do you think your work will eventually destroy all mankind?’ joked American comedian Stephen Colbert when he interviewed Church in 2012; Colbert later likened him to ‘a cross between Darwin and Santa’ in a piece for Time magazine, where he was listed as one of the 100 most influential people of 2017 (the previous year he had been tipped for a Nobel Prize).

Church, 64, made his name in the 1990s as part of the Human Genome Project, an international endeavour to sequence the whole human genome – in other words, to determine the exact order of all 6.4 billion letters of DNA required to make a single human being. It took over 1,000 scientists from 20 labs in six countries some 13 years and almost $3 billion to complete. Today, thanks in no small part to next-generation technology developed by Church, a whole genome can be sequenced using cutting-edge NovaSeq machines, which look a little like a sci-fi photocopier, in under an hour.

In 2007, Church’s biotech company Knome became the first to offer whole-genome sequencing (WGS) directly to consumers, initially for an eye-watering $350,000. Since then, prices have fallen through the floor: in 2016, another of his companies, Veritas Genetics, started offering WGS to consumers with a doctor’s sign-off for about $1,000. The purpose? To unlock the secrets hidden in people’s cells, from the frivolous (their predisposition to hair loss), to the functional (their chance of reacting badly to certain drugs), to the frightening (their risk of developing more than 1,200 partially hereditary diseases, including cancer and Alzheimer’s).

Many people would rather not know; others want to find out everything – and now that anyone can buy a mail-order kit from companies such as 23andMe online for as little as £149, DNA testing is no longer the preserve of scientists, but the subject of dinner-party conversation. The difference is, these cheaper tests rely on ‘genotyping’ – a snapshot of less than one per cent of your genome, which might miss many of the tiny variations linked to health and disease by only looking for those already known to exist. For example, there can be thousands of mutations in the breast-cancer-linked BRCA genes (Angelina Jolie decided to have a preventative double mastectomy after discovering she had one of the most harmful), but 23andMe only picks up three of them.

To Church’s frustration, those of us who are interested in finding out more about our DNA don’t tend to perceive this difference. But in technology terms, it’s a little like comparing a tricycle with a Tesla: getting your whole genome sequenced produces your body’s unique master blueprint, which can then be reanalysed whenever a new genetic discovery is made. And that’s not just useful to you, but becomes useful to everyone, if you allow it to be pooled with other people’s for use in research.

Church has been waiting for over a decade now for WGS to catch on, to kick-start the genomic age: a revolution that he believes will transform the health of every single person on the planet. Yet we’re still teetering on the brink. Because in a chicken-and-egg situation, in order to unlock the secrets that will persuade more people WGS is worth doing, scientists need to get their hands on more genomes.

Millions, if not billions, of them. Which is why Nebula Genomics, Church’s latest start-up, launched in November 2018, gives everyone the option to have their whole genome sequenced for free. (He’s getting this up and running in America, but it should be available to the rest of the world later this year.) Now, he says, he just needs to ‘explain it well enough that people understand why they should want it’.

At 6ft 5in, Church is a giant of science in more ways than one, with a grey mane, a thatch of a beard and an amiable manner it’s impossible not to warm to. Raised in the mudflats of Florida, he has a deep, mellifluous timbre to his voice, which rolls towards a reassuring ‘right?’ at the end of so many sentences that even the most radical ideas soon seem reasonable.

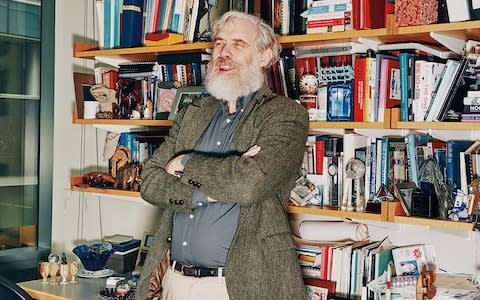

He keeps no secrets. His own genome and medical history are on his website for all to see – he was diagnosed with dyslexia as a boy and narcolepsy as a teen, had a heart attack at 40 and has been strictly vegan since 2004 – and he operates an open-door policy at his freewheeling lab that, in something of a rarity among scientists, he appears to extend to anyone who asks nicely. Journalists included.

Church shows me around in mid-December, three weeks after Nebula’s launch. Taped to a fridge is a picture of Darwin above the words ‘Evolve already’ – somewhat unnecessary, given that here, evolution appears to be going at warp speed. ‘This is a room I can’t go into,’ he says at a closed door behind which students are testing treatments on his own cells, which have been turned cancerous. ‘And over in that far-left corner was where we did the first cloning of engineered pigs.’ eGenesis, yet another of the 25 companies he has co-founded, is currently producing organs for clinical trials.

Then there are the ‘mini-brains’: cerebral ‘organoids’, again lab-raised from his own stem cells (‘I’m one of their favourite guinea pigs’), suspended in vast tanks of liquid nitrogen, which suddenly release their pressure with a startling hiss. Ultimately, they’re being used in an attempt to figure out which genes affect (and could perhaps fix) conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. In the meantime, ‘We have a betting pool as to when there’ll be more of my brain outside my body than inside,’ Church says. ‘Then I’ll challenge it to a game of chess.’

Right now, though, Church wants to get people talking about WGS and its benefits if enough people take it up – genetic matchmaking would be just one of them, helping to eradicate 7,000 severe Mendelian (single-gene) diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, altogether.

He’s not about to create an app that crosses 23andMe with Tinder himself, but the idea is not so far-fetched: Dor Yeshorim – a Jewish premarital screening service set up in the 1980s by Rabbi Josef Ekstein, who lost four children to Tay-Sachs – has now all but wiped out the neurodegenerative condition among the Ashkenazi Jewish population it most commonly affected. ‘A huge number of people use dating services, a certain fraction of the world has arranged marriages,’ Church points out. ‘I don’t think it’s fanciful [to believe] that we will get a little bit of help in deciding the shortlist of people to consider dating.’

Church met his own wife, fellow Harvard geneticist Ting Wu, back in graduate school and their labs now share a floor in the university’s glass-fronted New Research Building. When they had their daughter Marie in 1991, he was still working on WGS. But some two decades on, Marie, a body-products entrepreneur, and her husband both had their genomes sequenced before starting their own family. Happily, they were in each other’s 96 per cent: Church shows me pictures of his granddaughters, now four and one, who to his delight live right next door in the affluent Greater Boston neighbourhood of Brookline.

I came across Church when researching my own genetic history last year, after my mother and I took an AncestryDNA test (currently available on Amazon for £89). We sent off our saliva samples to be matched with the company’s database, in search of the biological father she had never known (a process I wrote about in this magazine earlier this year).

As many people took mail-order DNA tests in 2018 as in all previous years combined – meaning some 26 million individuals have now added their data to the four leading commercial databases (Ancestry, 23andMe, FamilyTreeDNA and MyHeritage), according to analysis by MIT Technology Review magazine.

At this pace, these companies could hold the genetic data of more than 100 million people by 2021, raising huge ethical and privacy concerns. Because unless you opt out (as my family did), the business model of most of them is to anonymise it and then sell it to third-party researchers. Drug giant GlaxoSmithKline bought a $300 million stake in 23andMe last year, while AncestryDNA had a deal to share longevity data with Google offshoot Calico.

It would be a failure of imagination not to wonder whose hands that data might eventually come into. Which is where Church’s start-up Nebula comes back in. Later this year, UK customers will be able to register on the website, and for £75 order a saliva-sampling kit, from which their genome will be extracted, sequenced, encrypted, then stored securely on the blockchain (the technology behind cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin).

That means that, unlike with some rival companies, you retain full ownership and control of your genetic code. You could choose to share it with your doctor, but it can’t be shared with researchers without your explicit consent. And if you participate in profit-making research, you share a cut of the spoils.

Church believes Nebula finally reaches the sweet spot of price point, medical quality and privacy that will induce enough people to sequence their genomes for scientists to make exponential leaps. An estimated 15,000 people had registered on Nebula’s website by the time I visited – I also gave a saliva sample to be tested, and am awaiting the results.

The NHS has engaged in the great gene race too. At the end of January, Health Secretary Matt Hancock announced the launch of a ‘genomic volunteering’ scheme, in which the NHS will sell a DNA-sequencing service to healthy people who want to predict their risk of developing various conditions, including cancer and dementia (and offer it for free to people with serious conditions).

Their anonymised data will be shared with researchers at Genomics England, owned by the Department of Health and Social Care, which has already sequenced 100,000 whole genomes from patients with rare diseases and common cancers – making it the world’s largest genomic database with associated clinical data. It is not yet known when the service will start or how it will work, beyond a plan to sequence five million genomes in the UK in the next five years.

‘Every genome sequenced moves us a step closer to unlocking life-saving treatments,’ Hancock has said. Critics claim it breaches a core principle of the NHS – creating a two-tier system, whereby people who can afford to can access services that are denied to others. That said, many geneticists predict that costs will tumble as uptake rises, meaning DNA testing of babies could eventually be as normal as the heel-prick test (for nine congenital conditions, cystic fibrosis among them).

‘But behind each of those sequences is a person,’ points out Dr Anna Middleton, head of society and ethics research at the Wellcome Genome Campus and Sanger Institute, near Cambridge. And the combination of genetic data with clinical and lifestyle history adds up to a ‘very, very, very valuable data set’. So valuable, ‘You start to think, where could that data end up?’

Last year, Genomics England confirmed it had fought off multiple foreign hacker attacks; by comparison, worrying about what Facebook is doing with your friends list is small-fry.

There is also the danger that your genome may tell you something you never wanted to know. Middleton previously worked in the NHS as a genetic counsellor, helping families with the psychological repercussions when something such as dementia, Parkinson’s or cancer was revealed to be on the cards. ‘What does it mean to have an inherited predisposition to something really horrible, that could potentially kill you?’ she asks. And not just you – but those you love, who share many of the same genes.

Middleton notes a striking split in her research, between genetic scientists (who tend to be male), keen for everyone to embrace genomic testing with urgency; and genetic-health clinicians and counsellors (who tend to be female), saying, ‘No, I have to pick up the pieces in my clinic.’

‘Genomics can be a very useful piece of the jigsaw,’ she says, ‘but we need to get everything in proportion. There are many world crises that need to be solved before you start getting everyone’s genome sequenced.’ But to Church, it seems little could be more crucial – and it’s not a question of if everyone in the world should get sequenced, but when. ‘Watch this space,’ he says, with the smile of a man who has seen the future, and is taking us there with him.

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security

Yahoo News

Yahoo News