For her many critics, arresting JK Rowling wouldn’t have made her anti-trans comments any less harmful

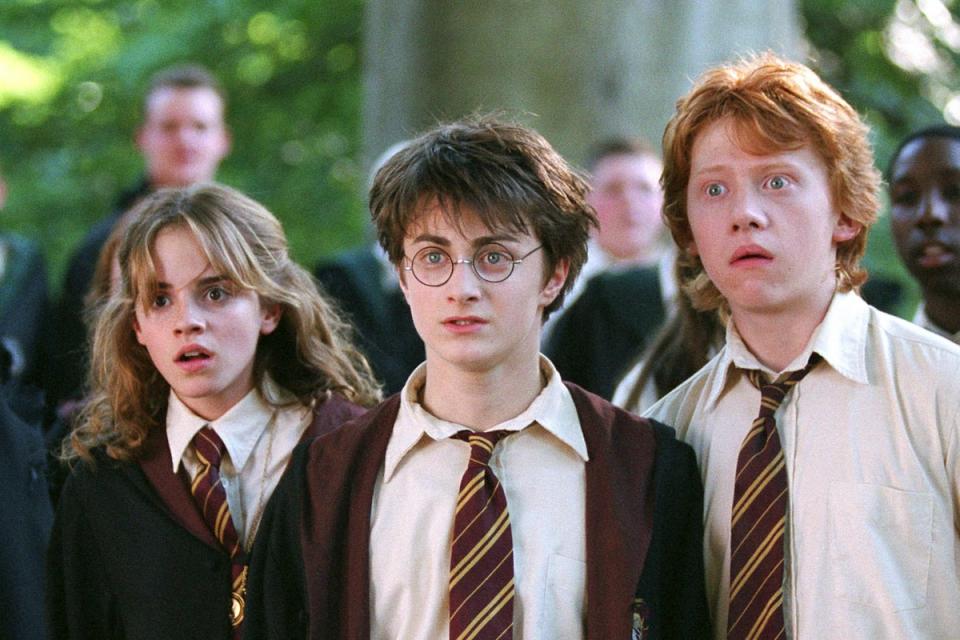

Arrest me,” wrote JK Rowling, at 11.45am on 1 April 2024. Despite the date, this was no April Fools’ prank. The Harry Potter author’s dare – aimed at the legal authorities in Scotland, where she lives – was entirely serious. It came at the end of an 11-tweet thread, 10 entries of which were dedicated to sharing names and photographs of different transgender women. Among these were several convicted sex criminals, as well as an athlete, the head of a rape crisis centre, and broadcaster India Willoughby. In one tweet, she details the crimes of a trans child rapist; in the next, she sarcastically praises Gaelic footballer Giulia Valentino for taking “some boring cis girl’s place” in a squad. Rowling wrote: “Obviously, the people mentioned in the above tweets aren’t women at all, but men, every last one of them.”

It is this rhetoric for which Rowling claimed to be inviting a police arrest; authorities announced the following day that they were taking no further action. Rowling’s comments came on the day that new hate crime legislation comes into effect in Scotland, which specifies protections for transgender identity, alongside disability, race (and related characteristics), religion, and sexual orientation. The bill, which was approved by Scottish parliament in 2021, also adds “stirring up hatred” as a criminal offence, something that has been a crime elsewhere in British law since the Public Order Act of 1986. Under the new act, the maximum penalty is a prison sentence of up to seven years. Women as a group are not protected by the Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) Act, an omission that has been criticised by Rowling and others. Per the BBC, the Scottish government is expected to introduce a separate misogyny law at a later date, following a consultation last year.

Rowling’s 1 April tweets have attracted criticism for the apparent conflation of trans sexual predators with the broader trans community – a neat microcosm of much of the broader transphobic rhetoric that pervades British discourse. But there’s little about her comments that is new. Rowling has wilfully misgendered trans women before; she has expressed a willingness to be arrested for breaking hate crime laws before; she has judged an entire minority group by the crimes of a few before. But Rowling’s tweets have grown bolder and more controversial in recent months. Last month, she was accused of holocaust denialism: replying to a commenter who made reference to the Nazi persecution of trans people and the burning of trans books, Rowling told them to “check [their] source for this, because it might’ve been a fever dream”. She was embroiled in a protracted public dispute with Willoughby, a trans woman, misgendering her and accusing her of “cosplaying a misogynistic male fantasy of what a woman is”. Willoughby wrote that she was “genuinely disgusted” by Rowling’s comments, which amounted, she wrote, to “grotesque transphobia”.

Go back even just a few years, and Rowling’s own tone was noticeably different. In 2018, after Rowling “liked” a transphobic tweet, the author’s spokesperson immediately distanced her from it. “I’m afraid JK Rowling had a clumsy and middle-aged moment and this is not the first time she has favourited by holding her phone incorrectly,” they said. She has denied being transphobic, writing on Twitter in 2020: “I know and love trans people[…] The idea that women like me, who’ve been empathetic to trans people for decades, feeling kinship because they’re vulnerable in the same way as women – ie, to male violence – ‘hate’ trans people because they think sex is real and has lived consequences is a nonsense.” As recently as 2023, she was arguing on The Witch Trials of JK Rowling podcast that her stance had been “profoundly misunderstood”.

Rowling’s contentions are essentially ones of free speech: that she holds certain beliefs about trans people that she should be free to express publicly, as she has been doing for several years. That these beliefs come from a position of feminism and a desire to protect the rights of cisgender women. It is, she writes, “impossible to accurately describe or tackle the reality of violence and sexual violence committed against women and girls, or address the current assault on women’s and girls’ rights, unless we are allowed to call a man a man”. She mentions single-sex spaces – public bathrooms and prisons being the most frequently set upon talking points, particularly as hotbeds of sexual violence.

It is estimated that trans people account for 262,000 members of the UK population; the 2021 census reported that 0.52 per cent of people who listed their sex as female identified as trans, and 0.56 per cent of men. As such, gaining any sort of reliable data is impossible. Asked last year about the violent crime rate for transgender people compared with the general population, the Office for National Statistics said it was “unable to publish prevalence estimates by gender identity because there were too few cases within those who identified as trans to produce reliable estimates”. The trans-exclusionary argument, such that it is, is forced to rely on anecdotal evidence, individual instances of crime perpetrated by trans people. This is no grounds for policy; plenty of cisgender women have also committed violent crimes, but it would of course be ludicrous to litigate around a presumed shared criminality.

What we do know of crime rates is this: data from 2022 suggests there were just 230 transgender prisoners out of a prison population of 78,058 in England and Wales – 168 of them trans women, and only six of whom were housed in female prisons. In Scotland, where Rowling resides, there were only 11 trans women (five in female prisons), out of a total of 284 female prisoners, and 7,220 men. Trans people are four times more likely to be the victims of violent crime than cis people. In the year ending March 2023, 4,732 hate crimes against transgender people were recorded – a rise of 11 per cent on the previous year – yet transgender and disability-based hate crimes were less likely to result in a charge than those based on other protected characteristics.

When it comes to the matter of women’s spaces, the issue with Rowling’s argument is partly one of practicality. With the tiresome “bathroom debate”, there is simply no way of implementing the kind of cis-only rules for which the anti-trans lobby advocates. The conversation, as it always does, completely elides the existence of trans men. If trans women are, as Rowling insists, men, then trans men are likewise women – and surely then entitled access to female-only spaces.

As Shon Faye writes in the 2021 book The Transgender Issue: “The logical endpoint of their ideology is that a person with a deep voice, full beard, masculine clothing, a typically male name and in some cases a penis will be permitted to enter a female space because he is a trans man or, in fact, just because he says he is (you cannot test for chromosomes in a public toilet).” The “false premise”, she continues, is that it is “always possible to detect a trans woman on sight” and deny her access to the women-only space. She adds: “This simply is not true in many instances, and could easily lead to a situation where masculine cis women and intersex women are challenged erroneously as ‘male’ based on their appearance.” Already, social media has seen cis women attesting to this experience.

Let’s get back to Rowling’s hypothetical arrest that wasn’t. Whether the author’s comments contravened the hate crime act was always a matter of some uncertainty. SNP minister Siobhian Brown had previously said that the act of misgendering – something Rowling has done many times – would not be classified as a hate crime. This week, she told Radio 4’s Today programme: “It could be reported and it could be investigated. Whether or not the police would think it was criminal is up to Police Scotland for that.”

In the wording of the bill, the ambiguity most stems from the issue of intent, and whether Rowling’s comments met the criteria for “stirring up hatred”. The first definition of the offence – which says it is a crime to behave “in a manner that a reasonable person would consider to be threatening, abusive or insulting” – has pretty clearly been met. Listing Willoughby and the other trans activists alongside convicted sex criminals is quite straightforwardly “insulting”, even if “abusive” or “threatening” are less clear cut. However, the definition also states that the person has to “intend to stir up hatred”, or that a “reasonable person would consider the behaviour or the communication of the material to be likely to result in hatred being stirred up”. This is where opinion muddies the waters.

For Rowling, it was a win-win. With Scottish authorities refusing to oblige her offer of an arrest, it is a vindication of sorts, proof that her opinions are not in fact hateful, as her detractors say. (How this freedom to misgender and offend would manifest in actual feminist advancement is unclear.) Were she to actually be arrested for her comments, on the other hand, it would have surely been read as an act of martyrdom – a woman being silenced for using her platform, an assault on free speech. “Bring on the court case, I say,” she wrote last year. “It’ll be more fun than I’ve ever had on a red carpet.” But plenty of people will struggle to find the fun in this debacle. Just because something isn’t a hate crime doesn’t mean it’s not harmful. Just because something’s legal doesn’t make it right.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News