Hiking the rooftop of Africa: Ethiopia's remote and beautiful Bale Mountains National Park

Hyenas are trying to eat our horses.

The night is oppressive. Inky black, heavy, still. But I can hear the pack outside the canvas of my rain-slicked tent, whooping like ghouls as they close in on our makeshift camp. “Ooweh”, the sound comes, again and again.

A fizzle of adrenaline snakes its way up my spine. I scurry out of my sleeping bag, pulling on my hiking boots and putting my hat on over unkempt hair. The camp has been illuminated by a sequence of fires, sending shadows dancing across our cluster of tents.

The horsemen are feeding the flames with gnarled branches, desperate to protect the horses that have so diligently carried our pots, pans and bulging bags up to this dizzying altitude. I rub my forearms to ward off the damp mountain air, keeping my eyes peeled for the flash of prying eyes in the moonlight. It’s 3am and there’s about to be a showdown. This is what life is like at the rooftop of Africa.

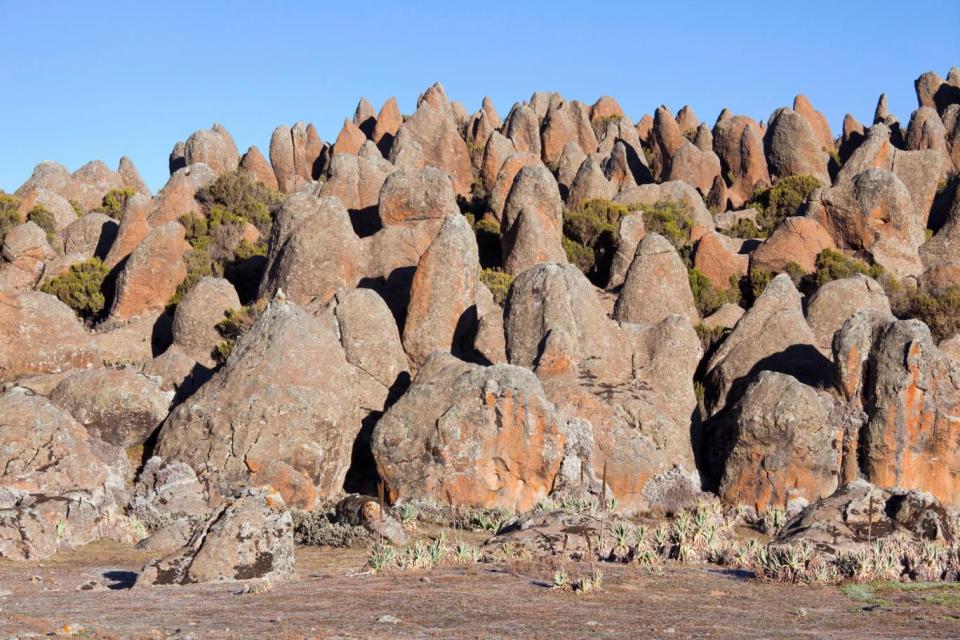

Ethiopia’s Bale Mountains National Park is an otherworldly place, strewn with Willy Wonka-esque giant lobelia plants, moon-like rock formations and oceans of wild heather spread like anemones across the ground. In south-east Ethiopia, roughly 250 miles from the capital Addis Ababa and home to the highest plateau on the African continent, it’s less visited than the Semien Mountains in the north. But it’s also home to some of Ethiopia’s rarest and most fascinating wildlife — from bizarre giant mole rats the colour of ginger biscuits and herds of elegant mountain nyala antelope, to soaring golden eagles and colossal swooping bearded vultures; known by locals as “bone crunchers” because they drop the bones of their prey from up high before descending to gorge on the spilt marrow.

But this is also the land of the Ethiopian wolf. The mountains are one of the only places on the planet where you can spot Africa’s most endangered carnivore and the world’s rarest member of the dog family (three times rarer that China’s giant panda). With current populations decimated by habitat loss and disease, such as rabies introduced by domestic dogs that roam the farmlands, it’s estimated there are now fewer than 500 of them left in the wild, marooned in a handful of isolated pockets across Ethiopia. It’s this white-socked animal that I’ve come to see.

I’m a couple of days into my six-day hike and, so far, it hasn’t been what you might call “a walk in the park”. The altitude is extreme — 4,000m, a height that can floor even the fittest sorts — and my body is taking a beating. My bones ache like rot has set in, my lips are bleeding and blistered, and a layer of grime coats my skin, forming a sharp line of black under my fingernails. But the landscape is enough to keep me pressing on. Our guide Ayuba — a kind-eyed man from the nearby village of Dinshoo — is also impeccable at noticing when it’s all got a bit too much for this delicate Londoner, often pausing thoughtfully to point out interesting pictures in his well-thumbed copy of Birds of Ethiopia, cocking his ear to every trill and whirr that drifts in on the wind, murmuring “augur buzzard” or “siskin”, with a small smile.

Thankfully, no blood was shed on the night of the hyenas, and as we plod along en masse the next morning, horses and horsemen pass me with infuriating ease; rare blue-winged geese, the most isolated on the planet, splash in glassy puddles around us; furious rock hyrax screech from their bluffs as we pass; and, across a ravine, a huge Abyssinian eagle owl is terrorised by a flock of rambunctious crows.

We trek through forests filled with wild rose and centuries-old trees. We skirt mountains that look like the skulls of giants, passing under shadowy flocks of ibis that cackle like witches. That evening we set up camp at the bottom of a cliff. “There are leopards here,” says Ayuba, gesturing casually to the putty-coloured crags. Sure enough, in the middle of the night, when I clamber out of my tent to use “nature’s bathroom”, I look up to see the stars spilling their silvery light across the mountaintops, but I can’t quite shake the feeling I’m being watched. When we eventually reach the Sanetti Plateau — an alpine grassland and known home to the wolves — it’s a bleak and blustery place, wind-pitted and pockmarked with scratchy highland shrubs. And it’s up there, in a place where time stands still and the rest of the world feels insignificant, that I see it — a flash of burnt orange. I raise my binoculars, my eyes settling on its rust-coloured flanks, its nimble legs, its unmistakable black-tipped tail. It is my very first wolf.

Moments later, Ayuba lets out a chuckle and we spot another, resting on its hind legs, its slim muzzle testing the air. Later that evening, as we set up camp, another two wolves trot by our tents — passing spry and spindly as the horizon pulls the sun downwards, sending swords of amber light across the land. This weathered place is so full of life; a haven for these wolves that are fighting to survive in this bleak but beautiful land. Suddenly, my limbs don’t feel quite so weary any more.

YellowWood Adventures (yellowwoodadventures.com) offers fully guided nine-day trips to the

Bale Mountains via Addis Ababa from £1,299.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News