Hilarious and honest or boorish and bigoted? Untangling the strange, enduring appeal of Jeremy Clarkson

Back in 2008, someone going by the name of “Joseph Dark” created a petition on the government’s official public lobbying system. “Make Jeremy Clarkson prime minister,” it demanded, simply. By the time it closed, it had received 49,446 signatures. Clarkson was not made prime minister.

In one sense, that demonstration of public approval is an extraordinary show of faith in Clarkson, the brash columnist and host of motoring programmes. But in reality, it represents a very modest degree of support. It is about 0.15 per cent of the 32 million-odd votes that were cast at the last general election, and only a bit higher than Tory MP Robert Courts’s mandate in Witney (33,856 votes), the constituency where Clarkson’s Diddly Squat farm, itself the subject of an Amazon documentary Clarkson’s Farm, is located. If he were to launch a coup, it would not be a very well-supported one.

And yet there was a moment in 2015 when it almost felt like it would come to that. A tank, organised by the conservative blogger Guido Fawkes, was driven through central London, to the doors of the BBC’s New Broadcasting House in Portland Place. Atop it stood a figure dressed as the “Stig”, the legendary professional driver from Top Gear, clutching a petition (another petition!) demanding that Clarkson be reinstated following his axing from the show. Perhaps more striking even than its delivery via a British FV433 Abbot armoured vehicle, was the fact that this petition had broken a million signatures. Throngs of fans greeted the tank, the Stig, and the petition at BBC’s HQ and cheered for their hero.

Of course, context is important. Clarkson had been sacked, not in some ideological purge – given his outspoken views on subjects like migration and climate change – or even because of a long string of accidents and controversies incurred during the filming of Top Gear. No, his end arrived, in the end, via a well-publicised “fracas” with one of the show’s producers, Oisin Tymon. A BBC investigation found that the producer was “struck [by Clarkson] resulting in swelling and bleeding to his lip” and that “Tymon offered no retaliation” at Clarkson. “The verbal abuse was directed at Oisin Tymon on more than one occasion,” the findings went on, “and contained the strongest expletives and threats to sack him.” The incident cost Clarkson his job at the BBC and £100,000 in damages awarded to the producer, but not – crucially – his reputation.

Today, Clarkson’s Farm, Amazon Prime’s warts and all depiction of life on a British farm, returns for its third series. The show follows Clarkson and his farm manager, breakout star Kaleb Cooper, as they struggle to turn a profit, fighting both the climate and bureaucracy. It is really a tale of green subsidies and red tape. But Clarkson’s Farm was not some PR exercise designed to restore the reputation of a disgraced public personality. Instead, it was the second show that Clarkson worked on for the streaming giant, Amazon, following The Grand Tour. Amazon paid an eye-watering £160m in a reported three-season contract with the team of Clarkson, Richard Hammond and James May (aka the Top Gear presenters). “They’re worth a lot,” Amazon head honcho Jeff Bezos, a man who knows something about value, told The Daily Telegraph at the time, “and they know it.”

The reason that they were worth so much is the same reason that a million people signed that petition. Clarkson inspires a unique form of adoration, predominantly among men of a certain age. He is an icon of an archetype that has diminished (or has been perceived to be diminished) in public life: the straight-shooting, no-nonsense, unapologetic man’s man. He graduated straight from regional titles like the Rochdale Observer and Shropshire Star to motoring mags and then Top Gear itself. Despite a middle-class background and education at Repton School in Derbyshire (there is also a branch of the school in Dubai, naturally), he has managed to maintain an image as a man of the people, in a manner not dissimilar to former prime minister Boris Johnson.

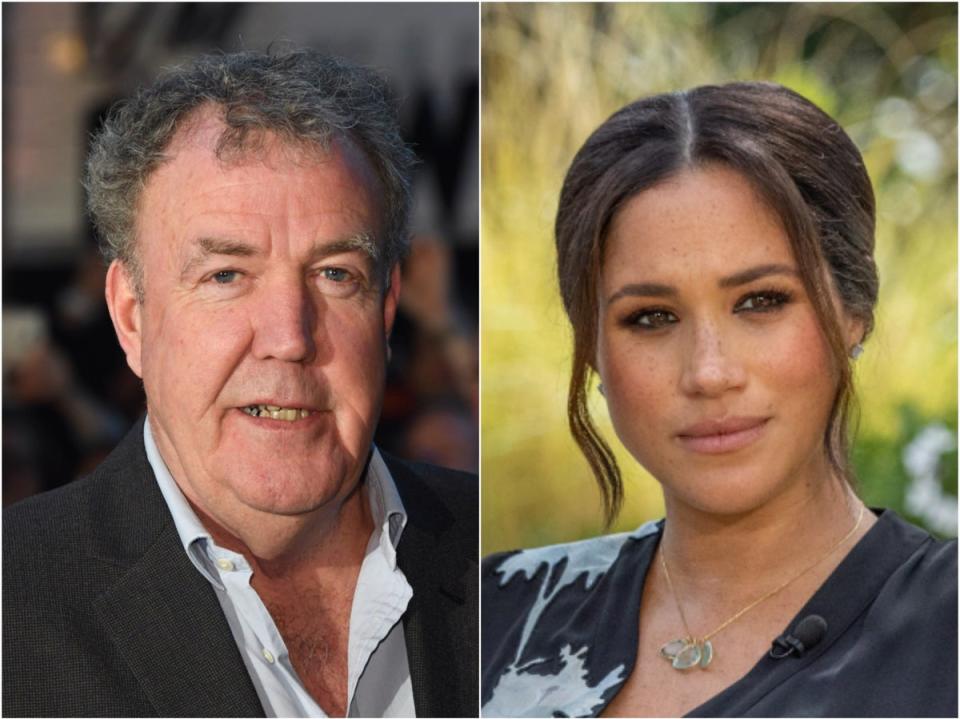

This has always been Clarkson’s position, at the centre of a tug of war between veneration and derision. He is loathed by people who see him as a standard bearer for a form of toxic machismo and a dinosaur on the 21st century’s biggest issues. Jokes made on Top Gear and The Grand Tour have regularly been decried as homophobic, while his writing has flirted with sexism and racism, culminating, infamously, in a column published in The Sun in 2022 in which he wrote that he was dreaming of the day when the Duchess of Sussex, Meghan Markle, “is made to parade naked through the streets of every town in Britain while crowds chant, ‘Shame!’ and throw lumps of excrement at her”. It resulted in public outcry, parliamentary condemnation, and a slap on the wrist from Ipso, the press regulator. Even Rishi Sunak, a man who prizes political expediency over all else, mumbled halfway to a critique by saying that “language matters”.

The Markle incident, like the “fracas”, has cost Clarkson. An Amazon executive told the Edinburgh TV Festival that they were “shocked and disappointed” by Clarkson’s comments, and rumours began to swirl that both The Grand Tour and Clarkson’s Farm would be finishing, effectively ending his relationship with the streaming giant. And yet, just as in 2015, Clarkson was offered a reprieve: in November last year, Amazon performed a volte face and announced the fourth season of Clarkson’s Farm, to follow the third one launching today.

He is like a human version of the optical illusion where some people see a rabbit and some see a duck. If you see a rabbit and believe him to be hilarious and honest (not to mention someone his fans voted, last year, “the UK’s sexiest male” in a poll for illicitencounters.com), you will take some convincing that he is, in fact, a duck. And those seeing a duck – a boorish, bigoted relic, who looks like a caricature of a small-minded little Englander – will never believe there’s a rabbit lurking there.

The truth is that Clarkson is half-rabbit, half-duck. A delicious hybrid animal that he would undoubtedly advocate the shooting of, followed by its preparation in a rich, gout-inducing sauce. He is a social conservative with strongly held views and a gift for articulating them, but he is also more pragmatic than his critics give him credit for. Clarkson’s Farm, for example, has provided a loud, clear voice for Britain’s farmers who are often elided from political discourse. If it weren’t for his tendency towards a self-immolating form of nastiness – whether administered via fist or pen – there would be much to admire about Clarkson. But he has a lot of second chances in an industry where most people don’t even get a first attempt.

After being dumped by the BBC, you’d have been forgiven for thinking that Clarkson was running out of options. But, for better or worse, he’s a survivor. And if even 0.15 per cent of the electorate would advocate for you, a TV presenter and hack columnist, to be prime minister, you’ve got a bargaining chip that will open a lot of doors. For Clarkson, it has been an opportunity to get his hands dirty, and finally plough his own furrow.

‘Clarkson’s Farm’ season three is out now on Prime Video

Yahoo News

Yahoo News