House of the Dragon just abandoned Game of Thrones’s ugliest habit

Within the spidery dialect of modern TV executives, there exists a sacred concept: the so-called watercooler moment. The phrase refers to a moment in a TV episode that becomes a point of widespread, fervent discussion – something that hypothetical office workers would discuss the morning after, while standing around their hypothetical drink dispenser, back when such a thing existed. For years, Game of Thrones was so chock-full of Watercooler Moments you would think it was getting kickbacks from Highland Spring. Shock deaths; beheadings; sexual violence; incest: scandalised chattering trailed the series at every turn. Thrones’s ongoing spin-off, House of the Dragon, began its second season this week with an episode that seemed similarly geared towards buzz and provocation. But this time, something was different.

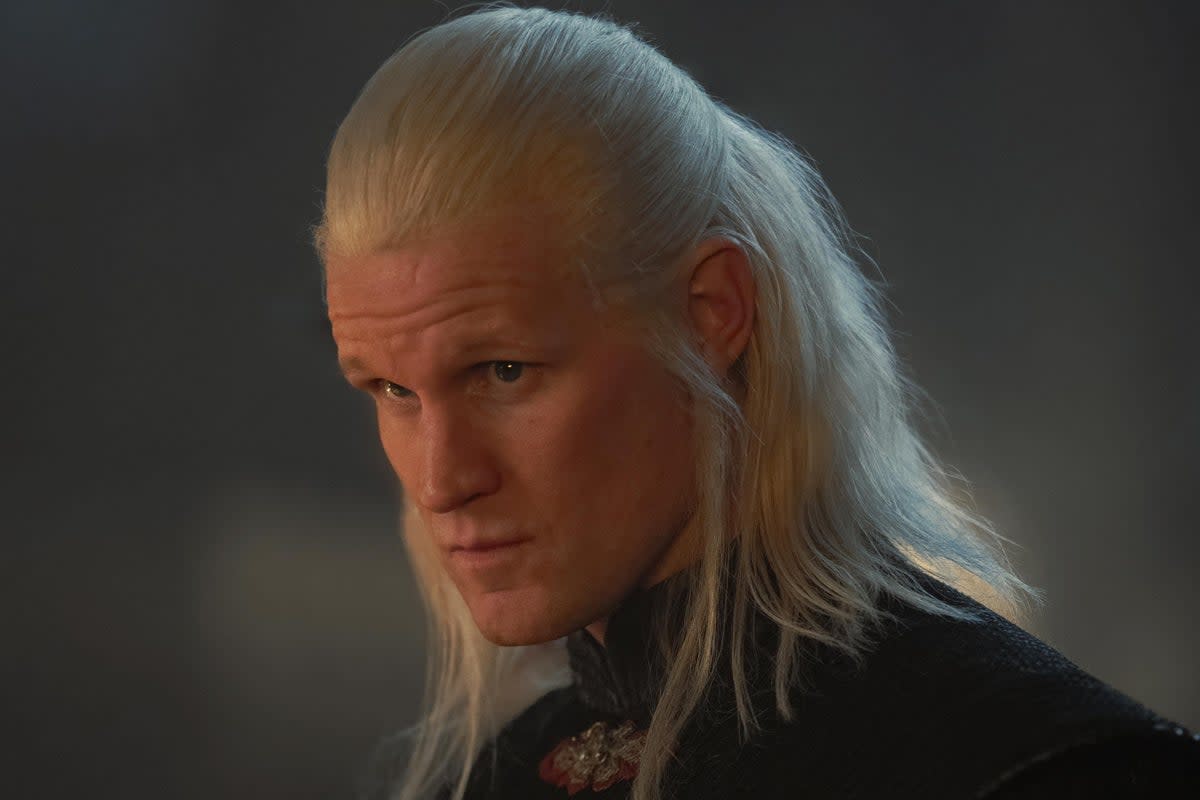

The episode, ominously titled “A Son for a Son”, is, for the first 45 minutes or so, something of a slow burn. (Spoilers follow, in case that isn’t obvious.) Picking up where the first season finished, the premiere sees the realm of Westeros on the verge of civil war, with the grief-stricken Rhaenyra (Emma D’Arcy) leading one side, and King Aegon (Tom Glynn-Carney) on the other. In an attempt to avenge Rhaenyra’s slain son Lucrys, the fiendish and flaxen-haired Daemon (Matt Smith) pays two grubby assassins to sneak into the palace and shuffle Lucrys’s cycloptic killer Aemond (Ewan Mitchell) off this mortal coil. But the plan immediately falls apart. They don’t find Aemond, and, like a Tesco delivery packer, decide to opt for a substitution instead: one of Aegon’s young children. Holding their mother Helaena (Phia Saban) at knifepoint, the two crooks force her to identify which one is the male heir, before beheading him. It’s grim and distressing stuff – but it could have been a lot worse.

Because if that sounds unpleasant, in the George RR Martin novels upon which House of the Dragon is based, the incident is considerably darker. There, the assassins, referred to as “Blood” and “Cheese”, threaten to rape Helaena’s young daughter if she does not play along with the Sophie’s Choice scenario. “A Son for a Son” tweaks this scene, removing the overt sexual threat. The actual killing, too, is done offscreen, in a manner that spares viewers the full gory horror of the deed. To be clear, it’s still startling – the murder of children is, after all, one of those soul-rattling taboos that mainstream TV shows seldom dare to depict. The scene may not be exactly tasteful, but the way it’s presented to viewers is a world away from the gratuitous excess of Thrones at its height.

It is, of course, not inherently immoral or problematic to incorporate sexual violence into a storyline, or to depict violence against children. But the changes House of the Dragon makes to its source material are deft because they recognise what is superfluous – what is misery simply for misery’s sake. Speaking to The Independent, Aegon actor Glynn-Carney addressed the scene directly, remarking that it would “split the audience”. He continued: “Some people turn on a show like this because they want that blood and gore, that shock factor. But I think what our imaginations can do is often way more shocking.”

This is the delicate balancing act that House of the Dragon is attempting: being a faithful and recognisable continuation of Thrones’s legacy that also addresses and avoids some of its predecessor’s most regrettable flaws. It is perhaps significant that Thrones’s original broadcast run (2011 to 2019) fell either side of the #MeToo movement. As the series progressed, the frequency and explicitness of its numerous rape scenes became a topic of mounting discussion and controversy, among viewers, critics, and (in interviews) its own cast members.

Glynn-Carney addressed this too, noting that “it did feel like maybe Game of Thrones was too close to oversexualising women, and that wouldn’t be cool if they did that this time”. If the early seasons of Thrones were made today, they would surely be made differently. And they might be better for it. Watching the season premiere, I didn’t for a second wish that the scene had been more explicit. Would there really be anything meaningful to gain from watching a child’s horrific execution in more vividly realised detail?

And yet, in sacrificing a bit of spice for the sake of good taste, House of the Dragon’s writers must also be wary of abandoning its brand – the propensity for sordid watercooler moments that made Thrones the defining TV hit of the 2010s. “A Son for a Son” suggests that the series is able to navigate these waters well. It’s a bleak and disturbing hour of television – but one that still knows where to draw the line.

‘House of the Dragon’ is available to watch on Sky and NOW in the UK, with new episodes arriving every Monday

Yahoo News

Yahoo News