How the first "driverless car" was invented in Britain in 1960

Fifty years before today's announcement of tests of driverless cars, a unique vehicle prepared for tests on the M4.

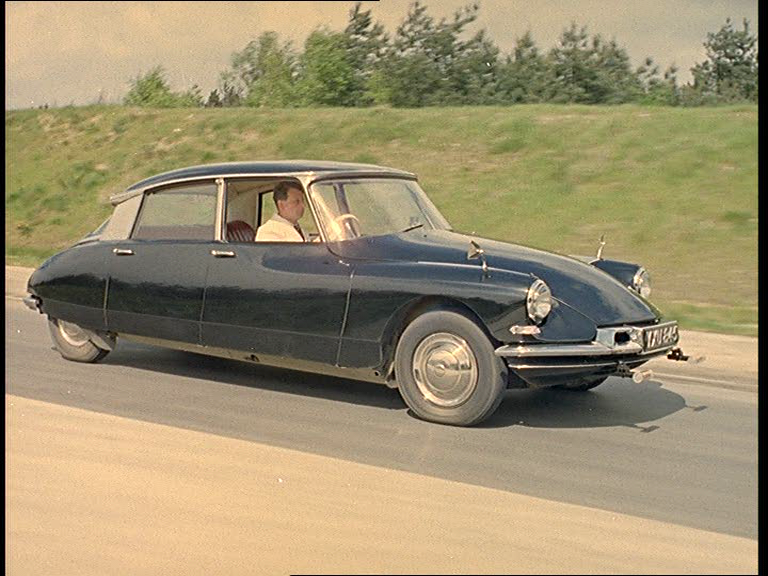

At a tiny test track in Crowthorne in Berkshire, a Citroen hurtles round a test track at speeds of up to 80 miles per hour. Conservative politician Lord Hailsham sits in the front, and theatrically takes his hands off the wheel to read a newspaper.

The steering is hydraulic, making hisses as every corner, and the car stays level and steady as it steers, piloted by sensors in the front and back. The driverless car is reliable enough for the engineers to persuade the government to prepare for tests on the M4.

The ‘car of the future’ - driverless, safe, piloted by electronics - had arrived.

But the maiden voyage of the driverless Citroen DS was nearly half a century before the UK government announced the first tests of driverless cars on UK roads, scheduled for the end of 2013.

[Related: Scientists power mobile phone using urine]

The Transport and Road Research Laboratory tested its cars - a Citroen, plus Minis and a Standard Automatic - from the turn of the Sixties onwards.

Looking at the 1960 Citroen DS - still intact, and shown off at a rally in Harrogate last year - it’s a rather different technology from today’s driverless systems.

The back seat provides room for a huge instrument panel covered in knobs and dials - under the steering wheel sits a large, square box which plugs into the car’s hydraulic steering, suspension and brake systems. The car is steered by magnetic sensors on the front and back - and drives along a magnetic ‘rail’ hidden under the road, like a Scalextric track.

The hurdle the engineers faced - and ultimately failed to clear - was how to make the machine change lane.

“It hadn’t seen the light of day in thirty years,” says photographer Hans Staartjes, a Citroen enthusiast who persuaded the Science Museum to show off the car at a rally last year.

“At Citroen rallies, you get a good dosage of anoraks who have seen everything. I knew one thing: they would not have seen this.”

“The DS was used because of its hydraulic steering, gear changing and brake activation. When you start up a DS the hydraulic system brings the car up to ride height.”

“Not much effort is required to activate these and they are very precise systems. The "driverless system" employed magnetic tracks underneath the road bed and a set of magnetic sensors both in front and behind the DS.”

“They got the car to go up to 80 mph on the track at Crowthorne and proceeded to build about 9 miles of track underneath the M4. I've heard rumours that that track is still there!”

Like many ‘new’ ideas, the driverless car is anything but. Facing the threat of congestion, several projects began to research ‘autonomous’ vehicles in the Sixties.

In 1969, the French governement began researching Aramis, a system that ran on magnetic rails, where drivers would sit in their own driverless carriage and join a ‘train’ of similar ones on the way to work.

Backed by defence companies - like many early “driverless’ systems - it was a costly failure.

In 1995, a Mercedes van drove 1000 miles from Munich to Copenhagen, overtaking other vehicles and changing lanes - using cameras to ‘watch’ the road, and computers to steer. The technology used was the forefather of many of today’s most talked-about driverless systems, including Google’s prototypes. Several states have now offered ‘licences’ for Google’s cars - which drive on roads with a dummy in the front seat to avoid terrifying other drivers.

So far, Google’s cars have been involved in crashes only twice - once with a human at the wheel, and once when a ‘Google car’ was rear-ended at a crossroads.

“We've successfully driven over 400,000 miles in self-driving mode across a wide variety of terrain and road conditions, and we're very pleased with the performance,” says a Google spokesperson. “Over 1.2 million people are killed in traffic accidents worldwide every year, and we think self-driving technology can help significantly reduce that number.”

“Self-driving cars never get sleepy or distracted, and their ability to make driving decisions 20 times per second helps them run smartly. Already there are indications that a self-driving car can operate more safely than an average driver.”

The company points out that it is currently focusing on refining its technology, rather than selling it to the public. Google is in discussions with several car companies.

Google’s theatrical demonstrations - letting a blind man ‘drive’ their cars - might not reflect how a ‘real’ driverless car would work, though. The LIDAR systems - laser radar - used to pilot Google’s cars are expensive. Radar boxes and cameras are far cheaper than scanning multibeam lasers.

Other, cheaper systems seem likely to take the wheel in ‘real’ cars first. BMW has driven a driverless model between Munich and Nuremburg. Both BMW and Audi predict driverless cars will be on the road this decade. Nissan, Ford and others also have their own systems in development.

“In most situations today it is very possible to have a car drive itself,” says Dr Chris Gerdes, who engineered an Audi TT which successfully navigated the Pike’s Peak mountain race in America. “If you take a US freeway or a British Motorway, it is not a difficult setting for the conventional technology we have, with cameras, laser radars, GPS etc. There is enough understanding for a car to be able to drive itself and to change lanes.”

“However the real challenge now is in making autonomous cars adapt to unusual situations. You may have an algorithm in your car designed to recognise pedestrians with two arms and two legs but people in Halloween costumes, for example, can look very different. Humans can pick that up but can the car?”

Mercedes new S-Class Limo uses 26 sensors including radar and stereo 3D cameras to build a ‘picture’ of the road. It recognises numberplates, and ‘assists’ with steering, braking and acceleration. The S-Class isn’t ‘driverless’ - if you take your hands off the wheel, it bleeps a warning - but it offers a significant helping hand.

“Driverless technology is already here: Volkswagens can brake themselves, Ford Focuses can drive themselves in congestion, and can parallel park themselves, and VWs can 'see' speed limit signs and project them on the instrument panel,” says Phil McNamara of Car magazine. “Tech historically starts on expensive flagship models, then trickles down (as did ABS and airbags decades ago). The new Mercedes S-Class limo will take the ‘seeing car’ concept even further.”

“The thing that will hold us back is legislation, which will be needed to make the car more autonomous,” says McNamara. “And the fear of class actions, if something goes wrong. Imagine if drivers could prove their cars' technology was responsible for an accident, rather than them. With whom does the ultimate responsibility lie?”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News