Hugh Hefner obituary

One evening in 1967, Hugh Hefner, who has died aged 91, appeared on a TV special broadcast from the Playboy Mansion’s library. Puffing on his customary pipe, and flanked by Harvard theologian Harvey Cox and conservative editor William F Buckley, the billionaire porn magazine magnate and American men’s titillator-in-chief argued that the religious basis for morality was obsolete.

If America was to fulfil its manifest destiny and its citizens were to genuinely enjoy life, it needed to be liberated sexually. This, he said, was what Playboy Enterprises, of which he was the CEO and visionary founder, was patriotically supplying. In this, arguably, Hefner was fulfilling his mother’s wish that he become a missionary. True, his work involved more pool parties, voluptuous women pillow-fighting and wearisome boasts about sexual prowess (“I have slept with thousands of women, and they all still like me,” he told Esquire magazine in 2002) than previous missionaries found necessary, but he always imagined himself to be a proselytiser for hedonistic anti-puritanism.

In the foreword to The Century of Sex: Playboy’s History of the Sexual Revolution, 1900-1999, he wrote: “Sex is the primary motivating factor in the course of human history, and in the 20th century it has emerged from the taboos and controversy that have surrounded it throughout the ages to claim its rightful place in society.” Others saw his impact on human flourishing somewhat differently. The feminist writer Gloria Steinem, who went undercover as a Playboy Bunny in 1963 to write an exposé of working conditions, said of her experience: “I learned what it’s like to be hung on a meat hook.”

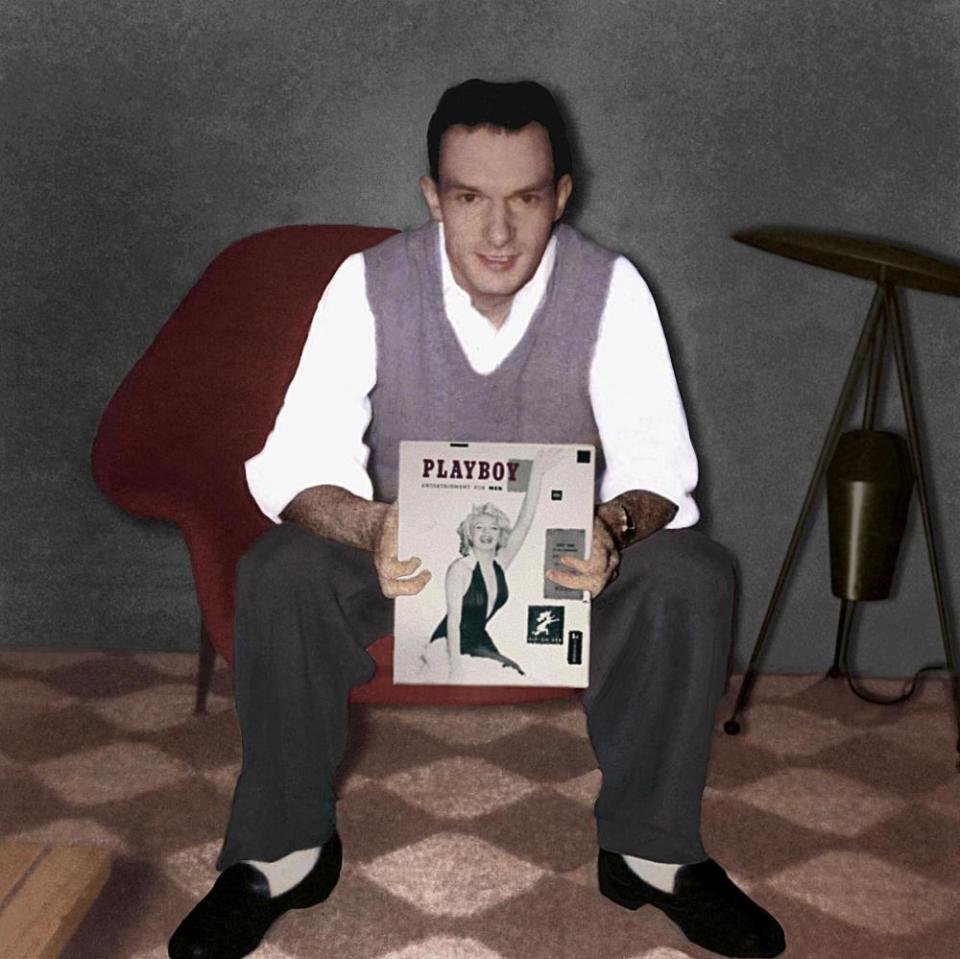

Whatever Hefner’s missionary pretensions, he certainly had business acumen. In 1953 he founded what would become a multi-billion-dollar industry with a few nude photos of Marilyn Monroe. The first issue of Playboy sold 50,000 copies nationwide. When, in 1963, he was arrested finally for selling obscene literature (after publication of an issue featuring nude shots of Jayne Mansfield), the jury was unable to reach a verdict.

His initial success fulfilled an adolescent fantasy. At high school he had written an essay criticising America for avoiding frank discussions about sex, and in his college newspaper he had hailed a study written by Alfred Kinsey called Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male (aka the Kinsey Report, 1948), which shocked America for frankly discussing such issues as sadomasochism, homosexuality and the frequency of marital sex. By publishing a magazine with two transgressive breasts on its cover, Hefner started a revolution. “The magazine reflected hip, urban dissatisfaction with the stodgy conformism of the Eisenhower era,” wrote Steven Watts in the biography Mr Playboy: Hugh Hefner and the American Dream.

According to Salon.com’s Chris Colin: “America was seeing the advent of the urban single male who, lest his subversive departure from domestic norms suggest homosexuality, was now enjoying new photos of nude women every month.” That bachelor was seduced not just by nude women but Playboy’s post-austerity aura of sophistication. Not all of Playboy’s demographic had grotto hot tubs, nor could they be reasonably expected to be pawed hourly by scantily dressed Playmates like their favourite magazine’s publisher, but they could aspire. Hefner became a fantasy figure, a lucky guy who, unlike his readers, was probably having sex right now, possibly with four Playboy Bunnies on a revolving bed. His readers dreamed not just of emulating Hef sexually, but of the whole Playboy lifestyle, one premised on cashmere sweaters, good pipes, fancy cocktails, essays by Norman Mailer and – crucially – no balls and chains or bawling kids. The conservative group Concerned Women for America claimed Playboy “belittled marriage”. Naomi Wolf wrote: “A lot of men stay unmarried decade after decade because they bought the Hugh Hefner line that polygamist bachelorhood is ideal, and they lead largely empty lives.”

This irrepressible swinger and/or corrupter was born in Chicago, Illinois. He was raised by Grace and Glenn Hefner in what he later recalled as “a repressed midwestern Methodist home”. His father’s lineage was impeccably puritan: he was directly descended from the Plymouth governor William Bradford. Grace, whom the adult Hugh would describe as running an unimpeachably puritan household, instructed him and his friends on the facts of reproduction from an illustrated book. Hefner later complained she had only taught him about sexual biology, not its emotional aspects. But Grace had thereby done more than most of his friends’ parents dared to improve her child’s sexual education.

The primal scene of his adolescence came when his drums-playing girlfriend Betty Conklin invited someone else to a hay ride, after a perhaps steamy summer during which she and Hugh had jitterbugged together. Stung by rejection, he reinvented himself as “Hef”, becoming, as he wrote in 1942, “a Sinatra-like guy with loud flannel shirts and cords in the way of garb, and jive in the way of music … A very original guy, he has his own style of jiving and slang expressions … He calls everyone ‘slug’ or ‘fiend’.” Improbably, the makeover worked: classmates voted Hef “most likely to succeed”.

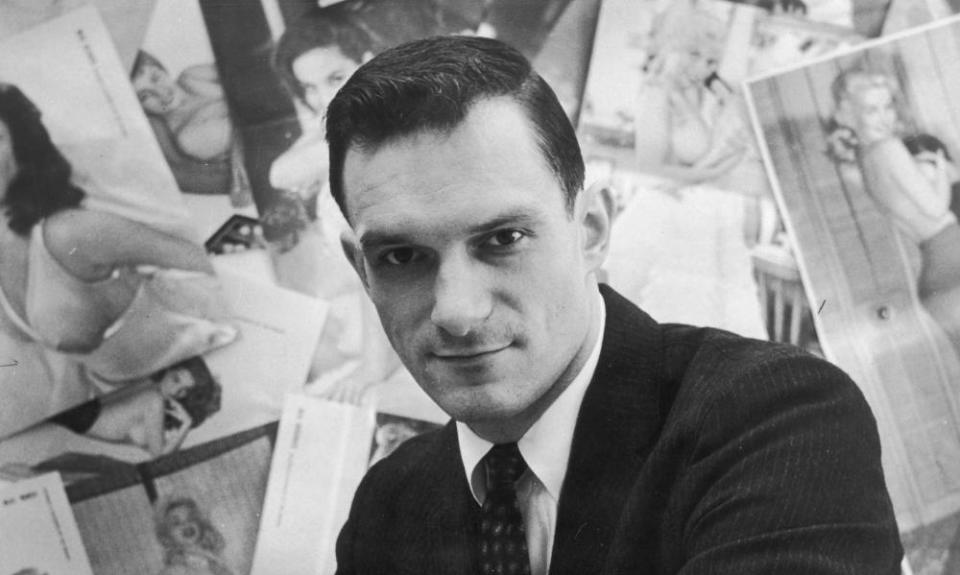

A decade later, though, success still eluded him. One bitter evening he stood on a bridge overlooking the Chicago river aged 26 and contemplated suicide to escape an unsatisfying marriage – to Mildred Williams, whom he had wed in 1949 – and a job that hardly fulfilled him. After a stint in the army and graduating with a BA in psychology from the University of Illinois, he had worked as a copywriter for Esquire. He quit in order to set up his own magazine, provisionally called Stag. Hefner took out a bank loan and raised $8,000 from 45 investors including $1,000 from his mother. “Not because she believed in the venture,” he told one interviewer. “But because she believed in her son.” Each issue featured nude photographs and a centrefold poster of the “playmate of the month”. But Playboy was not – or not only – what Tom Wolfe called a “one-hand magazine”. Hefner commissioned Lenny Bruce, John Updike and Jack Kerouac to write for him. Alex Haley’s Autobiography of Malcolm X was born from his interview with the leader in Playboy.

His marriage to Mildred, with whom he had two children, limped through a decade in which his career blossomed. Theirs became a proto-open marriage when she allowed him to sleep with other women. Mildred did so because she felt guilt over having an affair while he was away in the army and hoped that would preserve their marriage. They divorced in 1959. Hef’s swinging then began in earnest. He claimed to be “involved” with maybe “11 out of 12 months’ worth of Playmates” during the 60s and 70s. He also acknowledged that he experimented in bisexuality. His Playboy Mansion in Holmby Hills, Los Angeles, became a byword for sybaritic excess. He worked from his bed, often wearing silk pyjamas, happy to be, as he frequently was, distracted from running a global porn business by female employees.

Business boomed. Playboy Enterprises went public in 1971 at a time when the magazine was selling 7m copies worldwide each month. Hefner astutely diversified his brand: he hosted TV shows to proselytise for Playboy’s hedonistic male lifestyle, and ran a string of Playboy clubs staffed by that modern symbol of sexual infantilisation and female commodification, the Playboy Bunny. Each Bunny wore corset, bunny ears, collar, cuffs and fluffy cottontail. Clubs would have several sub-species of Bunny: Door Bunny, Cigarette Bunny, Floor Bunny, Playmate Bunny. There were even Jet Bunnies detailed to serve as flight attendants on the Playboy “Big Bunny” Jet. Clive James contended that “to make it as a Bunny, a girl needs more than just looks. She needs idiocy, too.”

“The training course was at your own expense,” recalled Steinem of the Playboy Bunny induction process. “It was horrible. There was nothing fun about it.” High heels and “costume so tight it would give a man a cleavage” were exhausting and demoralising, she reported. Steinem’s reportage helped make her a feminist: “In the sense that we’re all identified too much by our outsides instead of our insides and are mostly in underpaid service jobs, I realised we’re all Bunnies.”

Hefner, though, considered himself a proto-feminist. “In the 1950s and 60s, there were still states that outlawed birth control, so I started funding court cases to challenge that. At the same time, I helped sponsor the lower-court cases that eventually led to Roe v Wade. We were the amicus curiae [a friend of the court who volunteers information] in Roe v Wade [the 1973 US supreme court decision affirming a woman’s right to choose abortion]. I was a feminist before there was such a thing as feminism. That’s a part of history very few people know.” His feminism, if that’s what it was, stemmed from Hefner’s anti-puritanism. “Women,” he said, “were the major beneficiary of the sexual revolution. It permitted them to be natural sexual beings, as men are. That’s where feminism should have been all along. Unfortunately, within feminism, there has been a puritan, prohibitionist element that is antisexual. Playboy is the antidote to puritanism.”

That antidote to puritanism faced increasing competition from the 60s onwards. Magazines including Penthouse and Hustler battled for market share with Playboy. These were the years of the “pubic wars” in which rival porn magazines vied for how much skin – and pubic hair – they could get away with showing on their covers. Hefner, posturing as ever as putative sophisticate, declined to stoop to conquer in this battle.

In 1985 he suffered a minor stroke. His daughter Christie began to run the Playboy empire. In 1988 eight of his former lovers filed a $35m lawsuit against Hefner for that most Californian and thus costly of legal neologisims, palimony. The suit sought punitive damages to “dissuade him from maintaining long-enjoyed practice of seducing teenaged girls, supporting them for a few years and then discarding them”. Hefner told the press: “I’m the silliest possible target for a palimony suit, because I’m the most confirmed bachelor of the 20th century.”

In 1989, this confirmed bachelor married for the second time, wedding playmate of the year Kimberley Conrad. The couple had two sons, necessitating the transformation of the Playboy Mansion into a family-friendly home. After he and Conrad separated in 1998, she moved into a house next door. They divorced in 2010. During the couple’s separation, the Playboy Mansion and Hefner reverted to type. He kept a wide range of Playmates and became a devotee of viagra. The self-styled sex revolutionary was becoming a joke rather than a threat to American values.

In 2011 his planned wedding to Crystal Harris initially fell apart when his fiancee realised that “I wasn’t the only woman in Hef’s life.” She may have had a point. If he suffered after Crystal’s rejection, there were compensations: there always were for the oldest swinger in porn. He had once said: “I wake up every day and go to bed every night knowing I’m the luckiest guy on the fucking planet.” They reconciled and married in 2012.

At least half the planet’s population might have been excused for feeling less lucky. When he reopened a Playboy club in London in June 2011, 30 years after the original venue closed, one protester, Kat Banyard, director of UK Feminista, told reporters: “When it comes to today’s pornography industry, all roads lead back to Playboy.” He is survived by Crystal Harris, and children Cooper, Christie, Marston and David.

Hugh Hefner, born 9 April 1926; died 27 September 2017.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News