'My husband went fishing and didn't come back'

It was a scorching hot spring afternoon in 1984 - but Christine Huggins remembers suddenly going cold all over, as if 'somebody had walked over' her grave. She was out in Limavady, Northern Ireland, with her young son and friend Lynn, and distinctly recalls the 'chill' she felt - although at the time she couldn't place it.

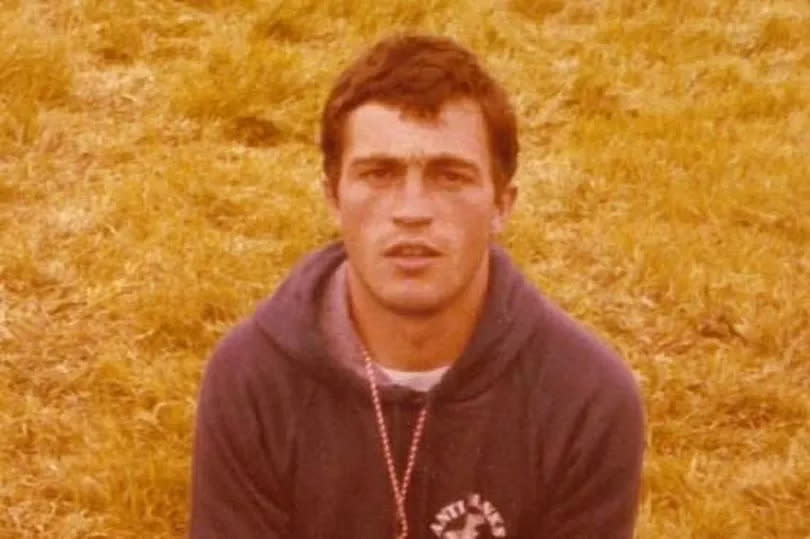

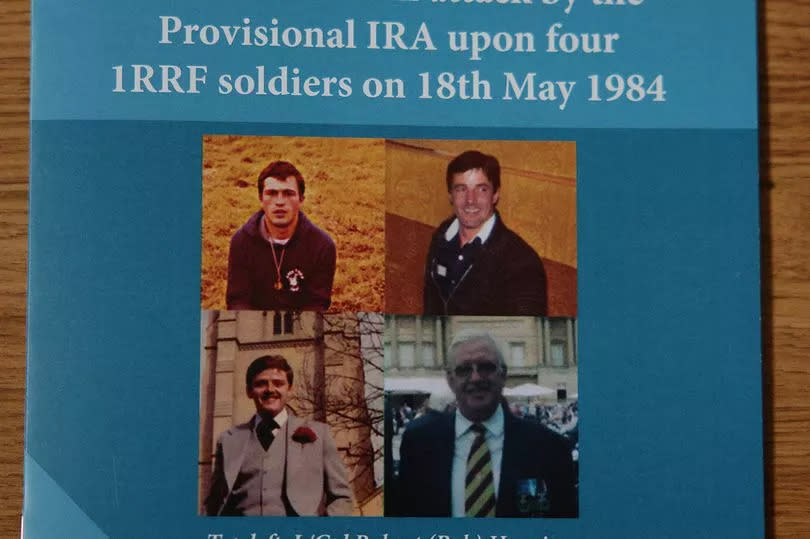

Some 70 miles away in Enniskillen, a car bomb had just exploded, killing two off-duty soldiers instantly. One of them was later named as Corporal Thomas Agar. The other was Christine's husband, Lance Corporal Robert Huggins, from Gorton. A third serviceman, Corporal Peter Gallimore, from Farnworth, would die of injuries suffered in the blast five months later, while the late Corporal Clive Aldridge, also from the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers, would lose both his legs before passing away in 2013. To this day, nobody has ever been charged with the bombing.

Robert had been on a fishing trip with his service colleagues when their van was blown up by an IRA bomb. In an instant, Christine's life fell apart. Left a single mother with three children, she moved back to Manchester. But, over the years, she has struggled to feel there is an understanding of The Troubles in mainland Britain.

READ MORE: Zoned out and frozen on a busy Manchester morning

Terrorism knows NO borders

The roots of violence which claimed Robert's life go back hundreds of years.

In the early 1600s, parts of Ireland were colonised by the English and given to Scottish and English settlers. Largely Protestant, the settlers clashed with the native Catholics, often resulting in bloody conflict.

In 1800, the Acts of Union abolished the Irish Parliament and incorporated Ireland into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. But, by the late 19th century, the Home Rule movement- run by nationalists advocating for the restoration of an Irish Parliament - was a strong political force. But many unionists - who were mainly Protestant - feared for their futures in a majority Catholic country.

From 1919 to 1921, the Irish War of Independence saw fighting between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and British forces. It eventually brought about the Government of Ireland Act in 1920, which partitioned the island into Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland - two separate jurisdictions that were devolved regions of the UK. Further fighting ensued during the Irish Civil War.

In December 1922, Northern Ireland opted out of the newly established Irish Free State. However, many nationalists saw this as an illegal split of the island against what the majority wanted.

In the 1960s, a non-violent civil rights campaign began in Northern Ireland demanding reforms, including an end to discrimination against Catholics in the region and reform of the largely Protestant police force. But many unionists disagreed with the protests, leading to violent clashes and the beginning of the period known as 'The Troubles'.

The British Government ordered the deployment of troops to Northern Ireland in August 1969, following civil rights protests and an increase in sectarian violence. Some Catholics initially welcomed the British Army as a more neutral force than the country's police, the Royal Ulster Constabulary, who were largely seen to be a tool of the Unionist Government in Northern Ireland.

But, following Bloody Sunday, where British troops 'lost control' and killed 14 people at a civil rights march in Derry in 1972, attitudes towards the British Army soured. As paramilitary factions along sectarian lines launched offensive campaigns, a cycle of terrorist violence, bombings, revenge murders and extra-judicial killings saw an estimated 3,600 people lose their lives, and 30,000 injured.

It's believed more than half of the dead were victims of the IRA's republican paramilitaries, like Robert Huggins, before a painstaking 1990s peace process brought an end to the worst of the violence.

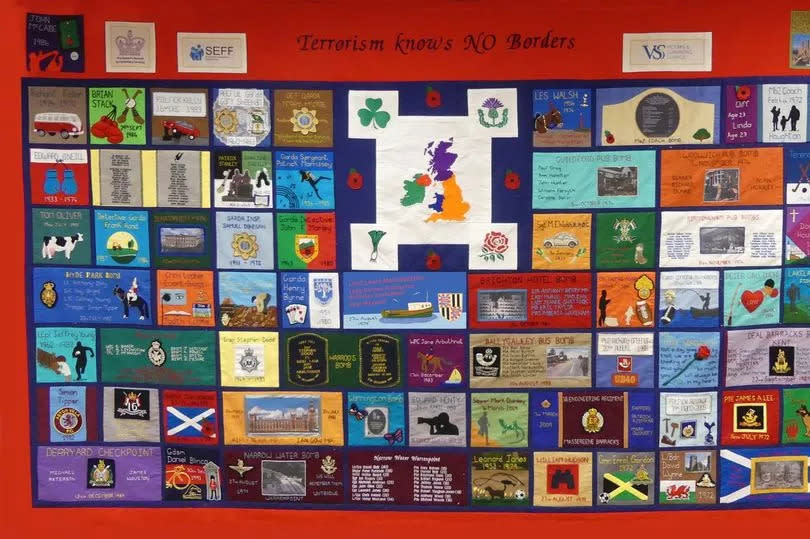

Now, 40 years after his death, Robert is one of a number of 'innocents' killed during The Troubles to be remembered on a memorial quilt commissioned by the South East Fermanagh Foundation (SEFF). The organisation is formed of a group of victims and survivors of The Troubles, with the aim of helping innocent victims of terrorism in the country.

The quilts will be coming to his hometown of Manchester to be displayed in the cathedral in an exhibition named 'Terrorism knows NO borders'. A service of remembrance will also be held at the cathedral, acknowledging the impact of The Troubles on Manchester and Great Britain.

'Maybe his spirit was around'

Christine and Robert met in Manchester just before her 17th birthday. The pair were introduced through a mutual friend at a youth club while he was on leave from the army, and had a whirlwind romance. Six months later, Robert was on leave again and they got engaged. Less than a year after they first met, the couple were married.

The Huggins moved to Northern Ireland in the January of 1984 after Robert was stationed at Limavady. "I was taken over by the army for what they call a 'reckie'," Christine recalled. "They used to take one of each of the wives of different ranks, so you go over and see it from your perspective.

"I'd been to Northern Ireland before and there were a lot of checkpoints, soldiers standing around checking bags, checking cars, getting on and off buses.

"But by this time a lot of The Troubles had calmed down, and it wasn't like that anymore. I felt very at ease."

Christine returned and gave a talk to other army wives about how safe she felt in Northern Ireland during her visit. Little did she know that four months later, her husband would be dead.

On May 18, 1984, Christine had just returned from an afternoon shopping in the town when a newsflash came through on her TV - two off duty-soldiers killed in a car bomb explosion in Enniskillen. She remembers not feeling concerned - Robert and his friends had gone out in a van, not a car, and there were four of them. If something had gone wrong, she was sure she would have heard from one of the others on the trip.

She cooked her children dinner and at around 6pm she sat down for the main news bulletin. The report was on again - but this time, she knew something was wrong.

"I just heard this voice," she recalled. "And the only way I can describe it is like when somebody's speaking to you, when you don't see them stood behind you.

"I heard the voice and it was Bob's voice, and he said: 'Chris that's me, do you understand?' And I just went, pardon?"

Beginning to panic, she ran down to her friend's house who had a telephone. "I was probably a bit hysterical," she said. "Annette [her friend] said, 'no, no, no, it's fine'. If anything would have happened Pete, her husband, would have rang her.

"I said, 'well it might not be him, but I know definitely it's Bob'. I said 'he's told me'. Well, obviously you can imagine her face looking at me.

"And at that point, my three boys came round and they asked if they could go to the park. I said, I've asked you to stay at home. You were having your tea, I'll be back in a second. My littlest one, who was four, he said, 'what's the point? Because dad's not coming back'.

"I asked him who told him that and he just shrugged his shoulders. I said, has anybody been to the house? He said 'no'. So why did he realize that? As they say, children pick up things. I heard his voice as clear as day. So maybe his spirit was around and his littlest one picked him up, was seeing it."

At around 7pm that evening, Christine was visited by the families officer at her friend's house, who told her that Robert had tragically died in the explosion. She remembered how she had gone cold in Limavady at around 4pm that afternoon, and found herself trying to explain to the officer that somehow, she already knew.

"Your whole world crashes down," she said. "On the Tuesday, a few days before it happened, I'd met one of the women from when we lived in Germany, whose husband got killed. And I said to her sister in law, 'I don't know how she's coping'.

"I said, 'if it was me I think I'd curl up and die'. And blow me down, did it not happen to me on the Friday."

The forgotten victims

Following Robert's death, Christine struggled to find any recognition in England for the men that had died in action in Northern Ireland. "There's nothing over here where we [bereaved families] can all get together," she said. "I found out a couple of months ago that there's actually a war widows group that you can go to, but nobody ever made me aware of that.

"Now, they have groups like that for children. But there was nothing like that for my boys, for them to go to off-shed their sorrows. And you're going through what you're going through. You can't really help them.

"I didn't have the internet when I lost my husband," she added. "Nobody ever comes forward to see if you're okay."

But, around 10 years ago, Christine found SEFF - a group of victims and survivors of the violence in Ireland whose entire purpose is to support those who have been impacted.

"Finding SEFF really helped me do better because it's somebody to talk to," Christine told the M.E.N. "Somebody understands you. And I just can't thank them enough for what they've done."

Robert's patch makes up part of a memorial quilt which is hanging in Manchester Cathedral as part of an exhibition organised by SEFF. When asked what it means to be bringing his legacy to his hometown in this way, Christine said she hoped it would be 'educational' to those who may not understand the cross-border impact of The Troubles.

"I think it's more for the fact to open the eyes of the British," she explained. "When you look at it, it could be their grandfathers on the quilts, or their uncle or their nephew, nobody knows until they see them. And you might be quite shocked when you read one of the little squares. Like Robert, I didn't know he had one."

Christine has made the trip to Enniskillen to visit a memorial bench there on several occasions, but said it felt important to be able to go and see something similar in Manchester.

"You just need something to keep it going and SEFF are the only people that have kept Bob's and Tom (Agar's) and Pete's memory going," she said. "I hope the young ones go and have a look at them, see what people went through, see what their sacrifices were to keep peace in the world."

The Memorial Quilts exhibition will be held at Manchester Cathedral between Monday 17 and Friday 28 June 2024. A remembrance service will be held at the Cathedral on Sunday, June 23.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News