‘Ian Dury was a voice for the disenfranchised’: Chaz Jankel, the man who made the Blockheads funky

Chaz Jankel walked cautiously down a corridor backstage at the Greyhound pub on Fulham Palace Road. Steam emerged from a dressing room, as if from a Turkish bath. Holding court in the middle of the musicians crammed inside, one of them eyeballed him. “Ere, do I know you? Well fuck off then!”

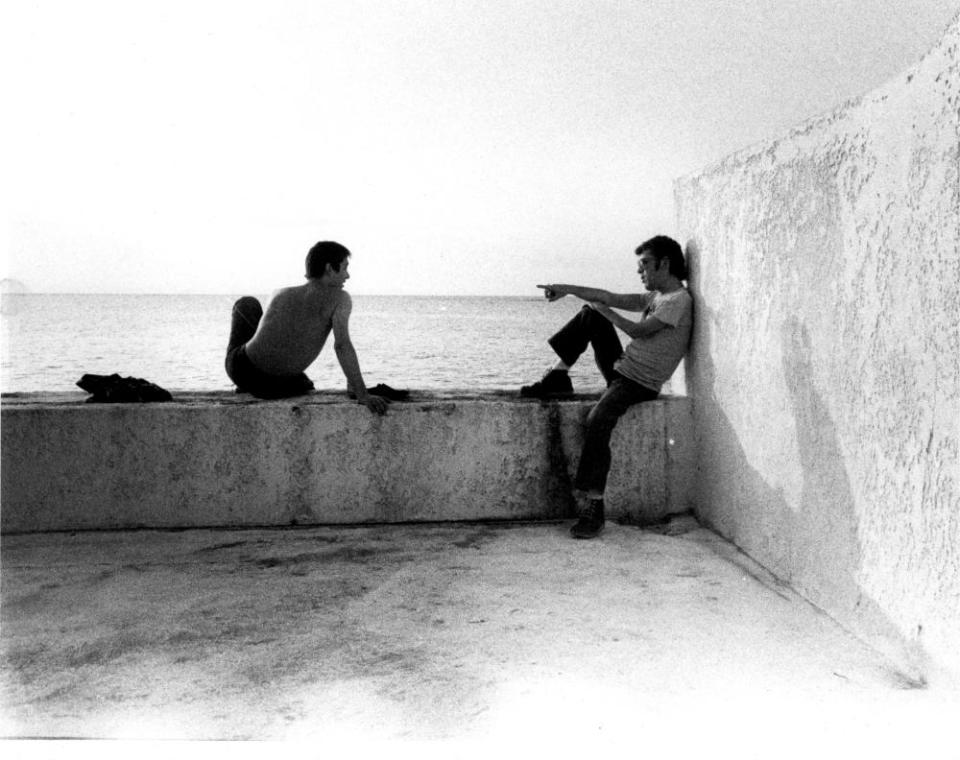

This was the inauspicious beginning of one of the greatest partnerships in British pop music, between Jankel, a middle-class north Londoner in love with Black American funk and soul, and Ian Dury, a confrontational, wildly charismatic pub rock singer. Jankel soon wrote the music for songs such as Sex & Drugs & Rock’n’Roll, Spasticus Autisticus, and the 1979 UK No 1 single Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick, with Dury delivering raunchy screeds on top. But this was just the first chapter in a remarkable story for Jankel, who would go on to become the darling of America’s club scene, be courted by Quincy Jones, and continue releasing music to this day: aged 71, he released his newest solo album last week.

Back in the Greyhound, Jankel was there because he’d been invited by Dury’s guitarist Ed Speight – their band, Kilburn and the High Roads, needed a keyboardist. “It was like watching a bunch of lunatics, really,” Jankel says of the gig he saw. “I didn’t particularly like the music but I was hypnotised. It was loud. It was surreal. Ian was wearing a Tommy Cooper fez; the sax player was the spitting image of Frank Zappa. It was like being hit over the head with a blunt instrument.”

After heading backstage and being rebuffed by Dury, Jankel turned to leave, but Speight spotted him and invited him to rehearse the following day. Jankel started gigging with them, but soon tired of the Wurlitzer piano lines he was playing: “It wasn’t soulful to my ears. I thought: I need more than this.” He coaxed Dury into writing new and different material with him, and they amassed a funkier backing band: the Blockheads. “Ian brought his love of music hall, and his sense of irony,” Jankel remembers, sat in the pleasantly skylit extension of his north London home. “And his anger.”

Dury was partially paralysed by polio he suffered as a boy. “If he hadn’t had polio, he would have been like Bugsy Malone or Ronnie Kray,” Jankel says. “But he put that anger into his lyrics and his stage persona – and we were his gang.

“He grew up in a very tough time in the 1950s where disability was the same as having a mental disorder. People were all just chucked together in the one home. And so discrimination and cruelty were massive in his life as he was growing up, and he channelled a lot of that into his lyrics. Also, the women he could attract doing music were a great spur to becoming a musician! He was also a very fine [visual] artist but he once said to me that when he realised he could never be as good as Rembrandt, there was no point doing that.”

The Dury-Jankel partnership quickly bore fruit. Debut album New Boots and Panties!! went Top 5 in 1977 and its follow-up Do It Yourself reached No 2; Dury had the vim of the punk scene he had helped inspire, but Jankel gave the Blockheads a danceable and almost sophisticated edge. “Ian was extremely articulate, energised, dynamic, funny, and 10 years older than me – so he was educating me about jazz and all kinds of things,” Jankel says. “Here is a person totally committed to truth and the written word. And as a lyricist, he was a voice for the disenfranchised.” He cites Billericay Dickie and Plaistow Patricia, larger than life working-class characters that appear on New Boots and Panties!! He says that people like this, “you never see them [in media]; politicians don’t give a fuck about any of them. If anything, right now I think there’s a move to get rid of people who don’t have any money.”

Spasticus Autisticus meanwhile – one of Jankel’s most insistently funky numbers – remains a heroically impolite, piss-flecked celebration of disabled humanity. It was banned by the BBC on release in 1981 but ended up being performed at the 2012 Paralympics opening ceremony. “The BBC thought Ian was having a go at disabled people. He wasn’t, he was just saying: hello to you out there, normal land. [Disabled people] were on the fringe and he was giving them a voice. So many people who are disabled have told me how important Ian is in their life.”

But Dury wasn’t an easy collaborator. “He was two quite different personalities – one when he was sober and one when he’d had a drink,” Jankel says. “Some people use alcohol as a foil to say what they want; dutch courage can take over and they can be a little bit vicious. Well, not a little bit.” Once during a rehearsal, Dury started kicking over the drum kit. “This random anger. Then went up to Ed Speight and cracks an egg on his head for no reason. Ed’s got yolk streaming down his forehead, dripping off his nose on to his guitar. And that obviously brought the rehearsal to an abrupt halt. So then the next day at rehearsal, Ian gets an egg and: bosh, cracks it on his own head. That was his way of saying: I was out of order. That expression, ‘out of order’, cropped up quite a lot.”

Another time Dury told Jankel to close his eyes during a writing session. He opened them to find Dury wearing fake horns with a torch under his chin. “He’s staring at me – and I shiver to this day. He wanted to play games like that, trying to say: I can be the devil.”

Jankel’s career prior to Dury had been almost nonexistent. His love for music began when he was very small, seeing Lonnie Donegan playing guitar, and became a means of escape in a boarding school that was both boring and violent – Jankel was beaten by older boys. “Music became that transport, where you didn’t need a passport, you go wherever you wanted in your mind.” Get Out of My Life, Woman by Lee Dorsey was his gateway into Black music, and he became a Sly and the Family Stone superfan right down to the outlandish fashion, even when playing west coast psychedelia in a band called Byzantium. “They had long hair and everything was denim, and I turned up wearing a sleeveless white satin waistcoat, bell-bottom trousers with red panels, and sequins. Looking back on it, I looked like someone out of Showaddywaddy.”

After leaving that band, he flatlined through his early 20s: smoking weed, living with his parents, and working listlessly in the lighting department of John Lewis until he left his phone number at a music shop that luckily found its way to Speight. But despite Dury and the Blockheads taking Jankel’s music to the top of the charts, “it was on Ian’s conditions. I thought, well, where do I come into this?”

Related: The 100 greatest UK No 1s: No 18, Ian Dury and the Blockheads – Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick

Inspiration for his first great solo single struck while on tour with the Blockheads – specifically, when getting high with a Dutch model in his hotel room after a gig. “She was offering me things that I’d never actually taken before. Things that aren’t necessarily legal. The melody for Ai No Corrida just popped into my head, and I just went over to my guitar, just to check what key this melody was in. I got so excited that I called [bassist] Norman Watt-Roy and said: come and hear this.” Despite this nerdish dampening of the romantic mood, the model stuck around. “It was very short lived!”

Ai No Corrida is an astounding song, wondrous to dance to. Its American lyricist-for-hire, Kenny Young, was inspired by the true story (dramatised in the film In the Realm of the Senses) of a geisha who becomes erotically infatuated with her madam’s husband, eventually losing her mind and cutting off his penis. “All I wanted really was a kind of lighthearted lyric – what the hell?” Even when turned into a tale of dreamy infatuation, its near nine-minute run time perhaps doomed it to failure, though it became a transatlantic hit when Quincy Jones (backed by Herbie Hancock and others) covered it as a three-minute single.

Jankel had a major label US deal with A&M, and his sense of funk meant that it was Americans who really got him: the equally superb 1981 single Glad to Know You became a ubiquitous hit in US clubs. Jankel was the guest of honour at New York nightclub Paradise Garage with its legendary DJ Larry Levan – “I got to stand in the booth with him, I felt like the bees knees” – and at Studio 54, where, after drinking a bit too much, “I lent on what I thought was a pillar, but it turned out to be a gigantic Christmas tree. Suddenly, this thing was moving, and it was like: timberrr! I ran to the circle of people trying to get out the way of this huge tree that was falling into the floor. I’m looking at it going, God, who did that?”

Dury wrote the lyrics to Glad to Know You, some of his best: “You wandered in upon my life / And haven’t lost me yet / Said the turkey to the carving knife / What you give is what you get.” Jankel says it was years before he worked out what Ian was saying: “Look out for backstabbers.”

Jankel performed it on a big US TV show, Dick Clark’s American Bandstand, and in an interview with Clark he cuts a strange shape: very handsome and cool, but also awkward and geeky, talking about music’s architectural properties. Was he a bit of an odd fish to be a pop star? “I was. I realised I could have trod a very commercial path with it all, but I was always dubious about polishing one’s ego that much.” Jankel minted other perfect pop songs – Number One, Without You, 109 – that are like Hall & Oates doing Italo disco, but none were actual pop hits, and A&M dropped him after his fourth album.

After spending the late 80s in LA scoring films he made his way back to the Blockheads, though Jankel chafed with Dury again, even threatening legal action to cut himself out of the band. But then Dury was diagnosed with the cancer that ended up killing him in 2000, and Jankel stayed. “I fell on my sword, let’s put it like that. And it was good – it was from a place of compassion. If you care about somebody, there’s always that forgiveness. I wouldn’t have been with him all those years if he wasn’t a very intelligent, compassionate, altruistic humanist.” Jankel still tours with the Blockheads: “The sense of democracy is phenomenal, that’s never been better.”

The same can’t be said for the rest of the world, and Jankel’s new album Flow rails against inequality, social division and the climate crisis. He’s been reflecting on “the huge chasm between wealth and the opposite. How are we gonna change things? Whenever you get a ray of light, it’s almost like it’s snuffed out – I mean, look what they did to Jeremy Corbyn.” But Jankel meditates and studies Eckhart Tolle, and is – understandably, in his nice house and with an esteemed career behind him – the picture of contentment. “You have to find that place within you that is untouchable by the comings and goings of these terrible events we’re going through. Anchor yourself in a sense of peace. Don’t be immune to what is going on, but don’t let it ruin your sense of self.”

He never really made it as a solo artist, was eclipsed by Dury’s brilliant ego and remains unknown to most, but he doesn’t seem to mind. “I had a song called You’re My Occupation – Tony Blackburn played it just once on the radio. But a woman who danced at a Spearmint Rhino strip club came up to me after a gig and said it was her favourite song to do routines to.” He gives a wry grin. “Success comes in many forms.”

• Flow is out now on CJ Records

Yahoo News

Yahoo News