Indigenous children in Colombia were given cameras to capture climate change. Here are their photos

A dried up water pool. Empty buckets. The relentless sun. These are a few of the things that Indigenous children in northern Colombia chose to focus on when handed cameras to capture climate change.

The Wayuu tribe have lived off the land for centuries, but a series of crippling droughts, erratic rainfall and extremely high temperatures are testing their ability to survive in La Guajira.

And, as in many parts of the world, it’s children who are bearing the brunt of this local climate crisis.

“Just one in ten Wayuu children has access to clean drinking water,” says Felipe Cortes, head of advocacy at Save the Children in Colombia. In La Guajira, the official death rate for children from malnutrition is six times that of the national average.”

To empower these young people to tell their own stories about climate change, and teach them new skills, the charity recently held a workshop in a small Wayuu community with award-winning photographer Angela Ponce. A dozen children were then given simple film cameras to document their lives for a week.

On Children and Youth Day at the COP28 climate summit, the resulting images are a powerful reminder of the need to centre children’s experiences and rights in climate action. With their soft focus and idiosyncratic choice of human and non-human subjects, they’re also a unique portal into the Wayuu community - as seen through the eyes of its youngest members.

Climate funds for Indigenous Peoples 'evaporate' before reaching them, report reveals

Viewing tower for Olympic surfing could destroy important marine ecosystem, activists warn

‘There aren’t seasons any more’: Water shortages in shot

In the arid environment of La Guajira, the climate crisis manifests primarily as a water crisis.

Following years of drought, water levels have hit historic lows. The water that is available is often taken from a 'jaguey' - a natural aquifer reliant on rainwater and shared with livestock.

This results in regular occurrences of diarrhoea and other waterborne diseases among children who are forced to drink the water.

“It hasn’t rained for a long time, and I think that we need the water and the animals do too,” said 14-year-old Ismael. “We drink the water from the cattle pond.”

Ismael also took a direct photograph of the sun. “I took a picture of the sun because it was too hot and that is harmful for the trees, and it makes us thirsty,” he said. “The heat makes us thirsty, and the cattle pond is far away… sometimes it’s empty and we need something to drink.”

Water - or the lack of it - is a common thread through the Wayuu children’s photographs, revealing their preoccupation with this vital resource made scarcer as global temperatures rise.

“Here, the Wayuu suffers from the lack of water. It can’t be found, as the weather is changing. There aren’t seasons anymore,” says 16-year-old Iveth.

“Before we had orchards, it rained, the plants grew. We didn't water the plants, the rain did. Now there's no rain, the weather has changed so we can’t sow. The plant’s leaves dry out due to the temperature and die.”

Using the sun’s light to capture Indigenous plants

The Wayuu children were also taught how to develop their own images relying only on the power of the sun, through a process known as ‘cyanotype’ printing.

The blue hue of these artworks illustrates the desperate need for water in the community, while framing the Indigenous plants that are essential for their survival.

14-year-old Belkis selected pods from a trupillo tree, which is bound up with the identity of the Wayuu people - who are the largest Indigenous group in Colombia.

It grows under extreme drought conditions, and so has been traditionally used as food for humans and animals. During the worst periods of drought, trupillo fruit is harvested and eaten as it was or made into flour.

“It's important that the animals are fed on trupillo so they do not die,” said Belkis.

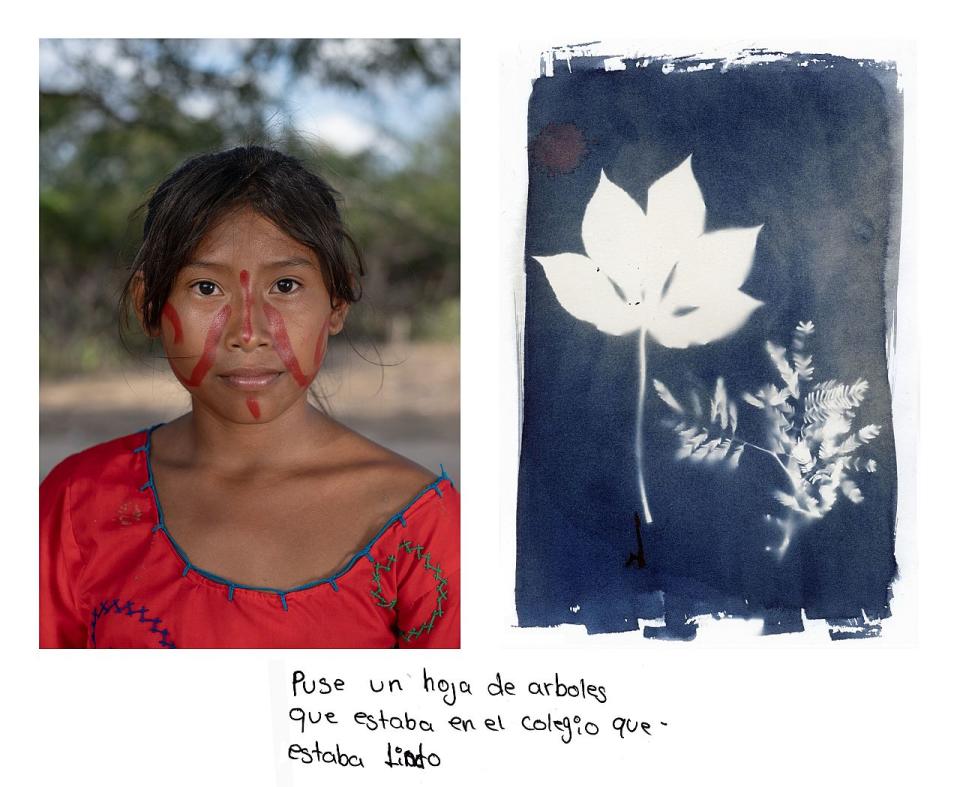

Manuela, 16, photographed a Yaichuaa leaf, a plant used to treat infections and kidney stones, alongside Apia leaves, which the Wayuu pluck the fruit of to cleanse blood in treating anaemia.

“I put a leaf from the trees that were at school and that were beautiful,” said Manuela, who lives with her mother, five sisters and older brother and knits backpacks to sell at the market.

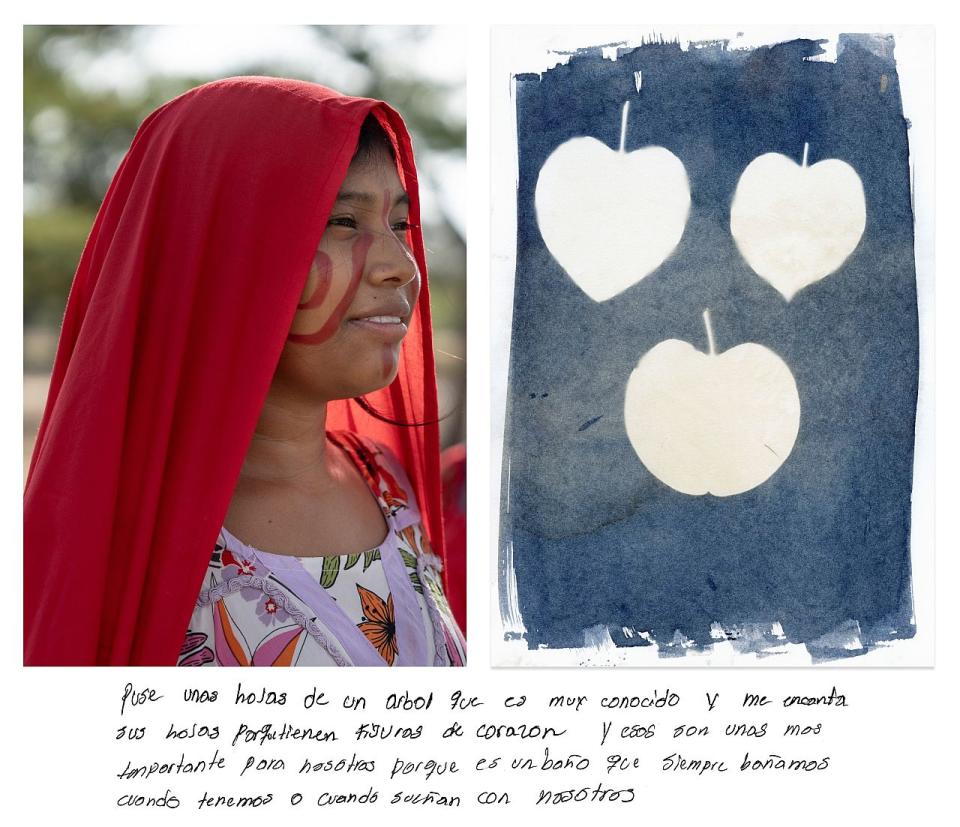

17-year-old Yolibeth’s choice has a more spiritual value. "I put some leaves from a tree that is very well known and I love its leaves because they are heart-shaped,” she explained. “It is very important for us because we bathe with them when we dream."

Dreams play a crucial role in Wayuu culture, acting as signals of events to come, she added. “We take these dreams seriously, using the plant in a midnight bath to interpret and respond to their meanings."

How are the Wayuu community being helped to cope with climate change?

The Colombian government has declared an economic and social emergency in La Guajira, which is home to some 400,000 Wayuu people, due to the unprecedented drought and impending impact of El Niño.

The region is already disproportionately affected by the changing climate, and temperatures are expected to rise by over 4 degrees by 2050, three times the global increase. Rainfall is projected to drop by one fifth. La Guajira is also the poorest region in the country, where over 60 per cent of the population live in poverty.

“The climate crisis, caused by adults, is putting nutritious food further and further out of reach - and harming children first and worst,” says Cortes. “Wayuu children, like others across the world, will be affected by decisions made at COP28 - and their rights and needs must be at the forefront of these decisions.”

Save the Children is calling for higher-income countries such as the UK to increase climate funding, to support lower-income countries, who are on the sharp end of the crisis.

“The climate crisis hits the most vulnerable the hardest, and it's heartbreaking to see children bearing the brunt of a problem they didn't create,” says Ponce.

“Handing the Wayuu children their own cameras gives them a voice to show the world the challenges they face. Their photos tell a powerful story of strength and resilience, highlighting the urgent need for all of us to protect our planet and support those most affected”.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News