How an inner-city motel became a detention centre for more than 100 refugees

Sami* has a few friends in Brisbane, where he’s lived for almost 18 months. Sometimes they’ll stop by his lodgings, an inner-city motel and serviced apartment complex. They’ll wave up to him from the street and call out his name.

Although Sami, 34, can wave down to Kangaroo Point’s Main Street from the balcony outside his room, he can’t stroll outside to greet his friends. Sami is a refugee and this hotel is a detention centre.

More than a year ago, private guards contracted by the Australian government moved into the Kangaroo Point Central Hotel & Apartments, turning it into something the government calls an “alternative place of detention”. They used the hotel (and a similar Apod in Melbourne) to confine people like Sami: refugees and asylum seekers who had been detained on Nauru or Manus Island and were sent to Australia for medical treatment. The hotel’s “guests” are not allowed to leave, not even to visit the KFC across the road. Now, thanks to coronavirus, they are not allowed visitors either.

Sami had just a few hours’ notice that he would be leaving Nauru, where he had spent five years and established a successful hairdressing business.

“I didn’t have a chance to tell anyone, even to bring my stuff,” he says.

One day in January 2019, he became dizzy and sweaty, thanks to a lifelong blood condition called G6PD deficiency. An ambulance took him to Nauru’s hospital and then to the refugee camp RPC1, where Australian doctors and interpreters were available. He remembers doctors saying they could not treat him and that he had to go to Brisbane for a blood transfusion.

“I said, ‘Please, does this mean I will die?’” he recalls. “They took my hand, they said, ‘Nothing will happen to you, they will come and an emergency small airplane will take you.’” During the four-hour flight he was “so scared”, he says. “I don’t know if I will live or not.”

Sami’s medical treatment — a blood transfusion and gallbladder removal — has long since finished. But he was not returned to Nauru as he expected. Nor was he released to the community, despite assurances from guards that he would only be detained for a few weeks while he recovered.

Instead, for the past 17 months he has been shuffled between another Brisbane hotel once used as an Apod, the Brisbane Immigration Transit Accommodation (Bita) detention centre, and Kangaroo Point Central. He doesn’t know when, or if, he will be released.

By the time Sami arrived at Kangaroo Point in the second half of 2019, about 80 refugees were already there. Back then, there were few clues for locals as to its real use. Men with walkie-talkies came and went from the premises, and some sat outside a building’s exit through the night. A carpark entrance was blocked off. But the detention centre was largely hidden in plain sight. Until March the hotel was still accepting bookings in its motel wing, where Sami now sleeps, for $95 a night.

Now there are more than 100 men held inside the hotel. Many were sent to Australia under the medevac law, many are still waiting for the specialist treatment they need, and many have been detained for a year or more. When coronavirus began to spread in earnest in Australia in March, Australian Border Force took over the entire hotel and moved dozens of refugees, including Sami (who had been returned to Bita), into the motel wing. The cat was out of the bag: now that the entire complex was a detention centre a fence went up, encircling the block.

Sami had always struggled at the Apod. His blood condition means there are certain foods he can’t eat and others — like chicken and processed foods — that doctors have advised him to avoid. But he cannot prepare his own food at Kangaroo Point and he says there’s often nothing suitable to eat. When he spoke to Guardian Australia on Monday, he did not eat the lunch or dinner provided that day.

He also claims he was assaulted by a guard in November. The guard still works at the hotel. His complaints about the food and the assault to the government and oversight bodies have gone nowhere, he says.

Ehsan*, who was 15 when he was sent to Nauru as an unaccompanied minor, the refugees in the hotel are “powerless”. He has lived there for almost a year, after being transferred to Australia alongside his cousin, also 22, who needed inpatient mental health treatment. Ehsan also suffers from depression and post-traumatic stress syndrome but has only seen a psychiatrist twice since August.

“They’re not listening to us,” he says. “They’re just watching our body language. And every time you say you want something, they say, ‘It’s not up to us, it’s up to Home Affairs.’ We’re tired, we just want to live our life.”

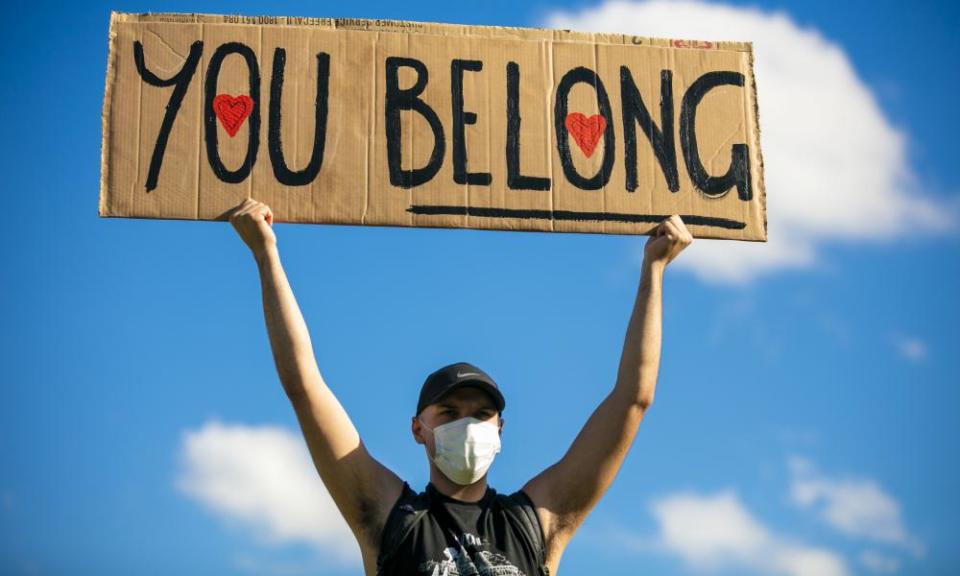

Crucially, when the government took over the whole hotel block, it gave refugees access to a balcony. In late March a guard’s positive Covid-19 test galvanised fears of a coronavirus outbreak in the hotel and detainees started a daily protest. Every day at 5pm they stand for half an hour holding signs and banners on the balcony.

Soon local activists started joining them for weekly protests on the street outside, jogging and stretching to avoid being fined for violating Covid-19 restrictions. The protests have swollen over the weeks: last Sunday hundreds of people came to a rally outside the hotel. At the rallies, detained refugees address the crowd through activists holding phones up to a megaphone.

“It made me so happy,” Sami says of last weekend’s rally. “When we see more than 2,000 people coming, oh my God.”

He says he wants the government to see the signs he holds during the balcony protests. “We want them to listen to us and give us our freedom, because nobody listens to you here.”

The protests have been a bright spark in an otherwise increasingly difficult time. “Everything is terrible when the coronavirus is coming,” Sami says.

He’s afraid detention staff could have the virus but says it is impossible to keep a distance from them. Without visitors, he has little to do. Excursions to Bita, where detainees could use the gym and do activities, have been halted for the last few months because of the coronavirus as well. He spends his time tending to an older, unwell detainee, or in his room.

For Ehsan, the protests are the only thing keeping him from dwelling on negative thoughts.

“Our mental health is getting really worse, day by day,” Ehsan says. “It’s detention life. You have no access to outside, you have no access to family support.” He has not been able to see his older brother, an Australian citizen who lives in Sydney, in months.

According to the acting immigration minister, Alan Tudge, the government has been forced to hold the men in Kangaroo Point because of the medevac legislation. People like Sami should take up offers to resettle in the US, he told ABC Radio Brisbane last week, or return to Nauru and Papua New Guinea.

But the government has not returned anyone to offshore detention in years, even when they have requested it. The US is not an option for everyone. Sami is still awaiting the outcome of his interview. Ehsan has been rejected, he thinks because of his Iranian nationality. (The Department of Home Affairs did not respond to a request for comment on its plans for the Kangaroo Point detainees.)

The government could allow Sami and Ehsan to apply for a visa, or even simply release them into community detention.

“I’m waiting every day if they will say to me, ‘You will go to the community,’” Sami says. “It’s really taking a long time.”

*Names have been changed

Yahoo News

Yahoo News