Inside 40 years of London Fashion Week — 'Madonna on the front row, Princess Diana popping in...'

London fashion week? We’ve had a few, 40 years worth in fact. The bi-annual riot has given rise to legendary industry moments, from John Galliano fresh from his Central Saint Martins graduate collection Les Incroyables to Bodymap choreographed by Michael Clark and Vivienne Westwood’s Harris tweeds. Let’s not forget Alexander McQueen’s extraordinary spectacles (spray painting Shalom Harlow!) Hussein Chalayan’s wooden table skirts; Victoria Beckham in hot pants at Maria Grachvogel and Prince (!) jumping up onto Matthew Wiliamson’s catwalk; Alison Moyet singing Only You live at Burberry and late Queen propping up the front row at Richard Quinn.

Aside from the intense creativity on show, it’s the flagship event for the British fashion industry which employs 900,000 people and contributes around £21 billion to the UK economy. While we might not command the financial might of New York, Milan or Paris, we’ve always punched above our weight when it comes to talent.

LFW was the brainchild of Lynne Franks, the notorious PR legend. Without her perseverance the fashion world would be without two of its most beloved - fashion week and Absolutely Fabulous. Franks was the inspiration behind Edina Monsoon. Sam McKnight, the titan hair stylist recalls working with her on his first ever show for Katherine Hamnett. “We did a Miss Moneypenny type hairdo, and set the hair on rolled up magazines, so the girls had these Sixties flick ups with headbands. Lynne always wore the clothes of the designers she represented. She turned up at the party, wearing the full Katherine look and one of the wigs and headband and I just thought, my God that is dedication to the cause.”

In the early Eighties, there were small showrooms and disparate exhibitions but no central schedule or space to entice international buyers to take London as seriously as the other fashion capitals. “We were not on the international calendar at all” recalls Franks, who’d come back from Paris impressed by its tents at the Louvre. “I thought if they can do it, why can’t we?” The first venue was the Commonwealth Institute (now Design Museum) in Holland Park, until the weight of the tents sunk the grass. Franks, who helped launch the British Fashion Council, funded the venture with backing from her client Mohan Murjani, the investor behind Gloria Vanderbilt jeans and Tommy Hilfiger, and brought in sponsorship from Swatch and Harrods. It moved to the Duke of York Barracks (now Saatchi gallery) on the Kings road. “We had Boy George, Spandau Ballet, the designers and press loved it. We had Madonna sitting front row at the Joseph show, [Princess] Diana would pop in. It was really vibey.”

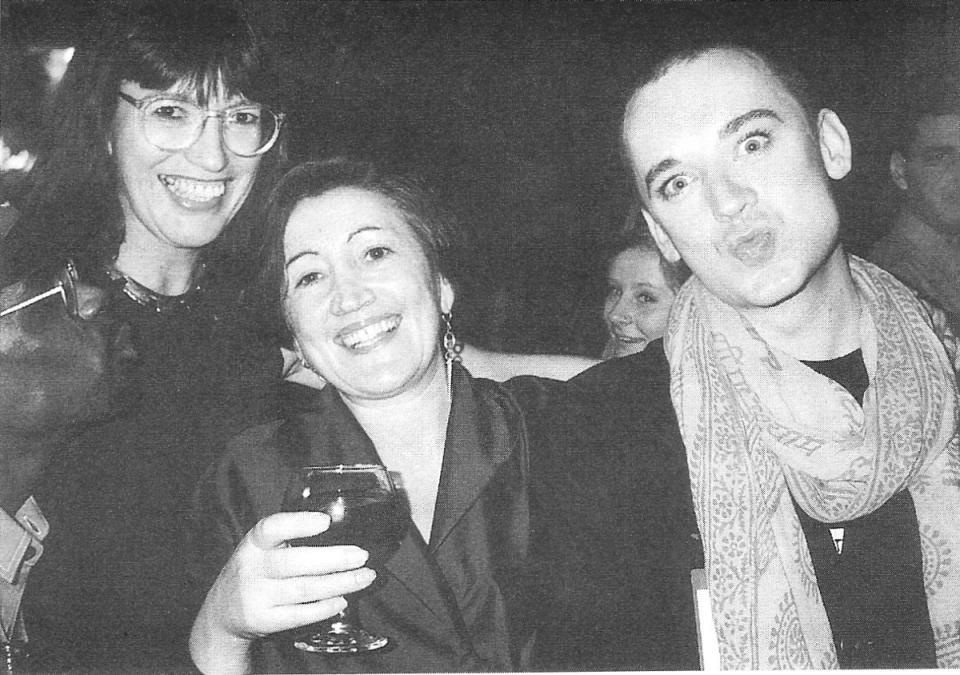

The fun was quashed when the trade show at Olympia felt left out and they ended up moving it further out West, to the less glamorous car park next to them. “It was never really the same after that, Katherine Hamnett and Vivienne Westwood went to Paris”. Fatefully, she asked French and Saunders to the British Fashion Awards; they hung out with Ghost’s Tanya Sarne and Betty Jackson, and thus, the legend of Eddie was inspired. “At the time I was up my own backside and hurt” laughs Franks of Ab Fab, “but it was very funny. It’s a bit of an honour, I took myself very seriously. Jennifer called me and asked if I wanted to do a cameo and I said “no thank you very much”. I mean what a silly thing, I should definitely have done that.”

Last September the BFC announced £2 million of government support for the New Gen talent scheme, but back then, they were on their own. “Fashion was still a bit of a dirty word in this country” remembers Jasper Conran, winner of designer of the year in 1986, and part of the first ever fashion week. “We were all permanently tempted to show somewhere else. But London was this melting pot of different ideas, each [designer] had their own look coming from a different angle.” “Backstage we’d have Christy Turlington and Naomi, Kate Moss - her first show was one of mine. It’s not the party you think it is. It’s monstrous pressure. It’s terrifying, and it goes by in a whirl.” And afterwards? “I got quite drunk”.

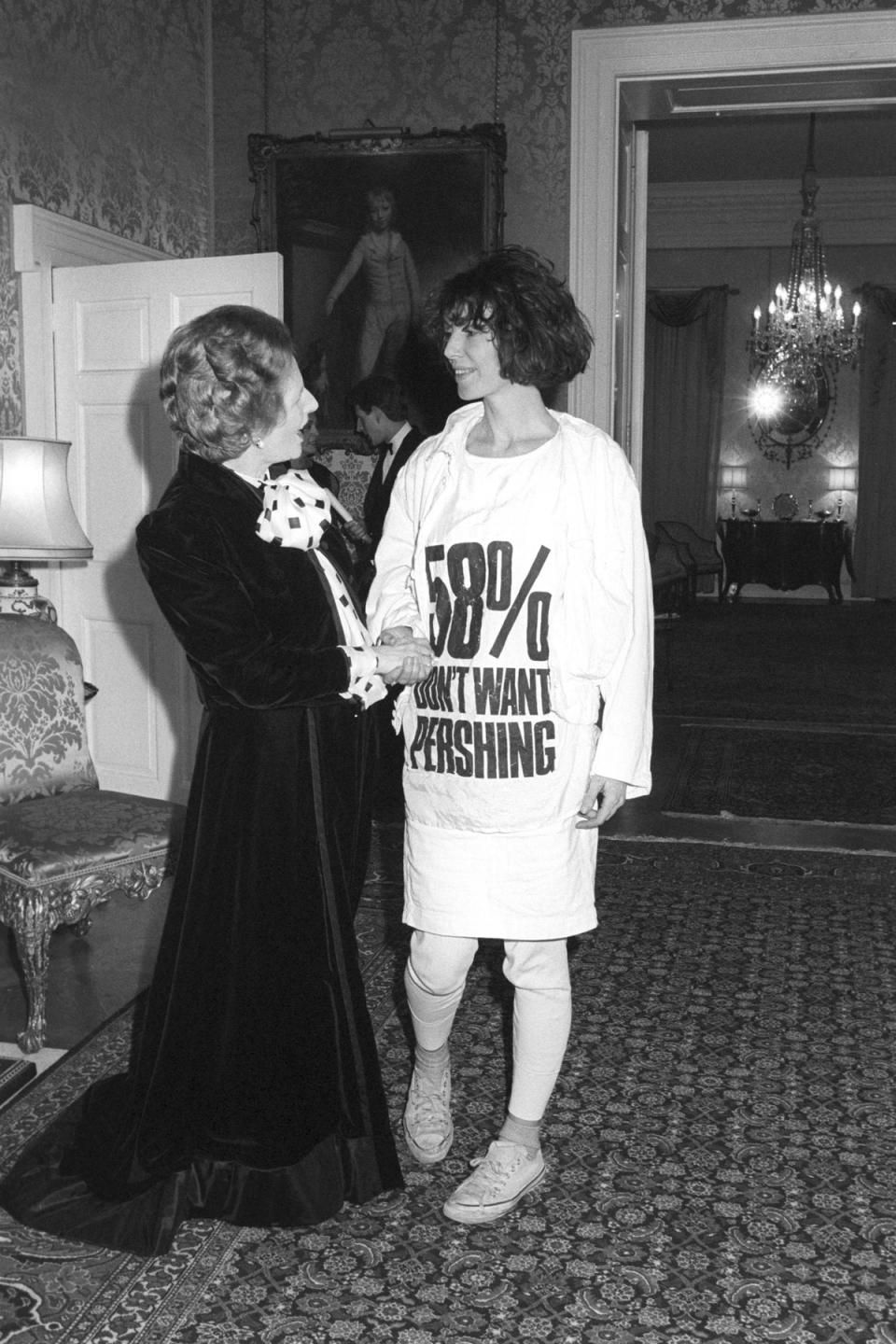

Money and a talent drain have always been the balancing act of whether the shows would go on. In 1993, Lowri Turner, this newspaper's then fashion editor, reported on how the whole thing was saved at the last minute by £30,000 from then trade secretary Michael Hesletine. Mrs Thatcher, while inviting designers to Downing Street receptions for its halo effect (which slightly backfired when Katherine Hamnett turned up in her infamous 58% Don’t Want Pershing T-shirt) had offered no money from the trade department under her reign.

But out of the Nineties recession, and inception of the New Gen initiative, rose the breathtaking talent of McQueen and Chalayan and a tricky truth: creativity flourishes in a downturn. “In London, we didn’t have the money” Turner remembers, “we hobbled from season to season. There was a buzz around young designers who initially showed in London but the moment anybody got successful, they went abroad.” She was at Alexander McQueen’s early shows, “I remember thinking he’s really talented. He had dripped latex down the hem of things. I did a review and said that it looked like snot, because it did! But they were really upset.”

Show reviews then could make or break a designer, there was no other conduit between them and potential customers. The press had huge amounts of power, there were no influencers, no smart phones, it was a closed shop.

After a show, Turner would “nip back to the office to develop the pictures in the dark room, or in the bathroom if there wasn’t time. You’d put the negative on a light box, everything is reversed. Dark is light, light is dark. It was a skill to [select] the best picture. You could always spot Naomi Campbell, she had a way of walking where she bent her body in a perfect S shape.”

In the newsroom “every Friday night was a party. I had a fridge under my desk entirely stocked with champagne bought from the stationery budget. I smoked about 50 cigarettes a day then, I remember turning over my keyboard and all this ash fell out.”

In the mid Nineties London had its Cool Britannia rebrand and everyone wanted in. Miu Miu and Tommy Hilfiger brought their shows here. By the end of the decade Matthew Williamson and Stella McCartney had enlisted Kate and Naomi to propel their first shows onto the front pages. Mimi Spencer, then Evening Standard fashion editor, wrote of “women draped in pashmina scarves” and “arriving at Matthew Williamson to find a warm sea breeze under seat and - hell you would - take a slug”. (A sea breeze was the cocktail du jour - if you remember having one of those at the Met bar, well, you probably weren’t there).

“Jade, I want you to freak out”

Lee Alexander McQueen

McQueen had yet to leave for Paris and had the budget to perform his extraordinary showcases. Model Jade Parfitt’s first show aged 16 was Prada in Milan, 1995, but back in London she remembers his shows as a “brilliant creative chaos”. She was in his extraordinary Voss spring summer 2001 unveiling, where the audience sat outside a huge glass, mirrored box, inside, the walls padded to echo a psychiatric hospital, the models appeared in dramatic turns unable to see the guests watching on.

Parfitt’s look included enormous taxidermy hawks strapped to her head. “It was Lee that fitted the birds onto my shoulders. You’ve got Kate Moss and Erin O’Connor and Karen [Elson] in the show, everyone was cheering each other on. These days you’d have eight million rehearsals and a movement coach to direct but my entire instruction was “Jade, I want you to freak out.” It was quite an unusual, disconcerting experience, but he knew he could ask us to do certain things and we would just go for it, you’d do anything for him. It was such an honour to be in that gang for a minute.”

Paris might have its swathe of decadent locations, but only London can take you from a leaky old warehouse dodging a dripping ceiling to the marble floored, glass-roofed Italianate grandeur of the Foreign Office’s Durbur Court (where Vivienne Westwood once led her finale carrying her climate emergency protest banners).

One of the first fashion shows I got into was Julien Macdonald, sometime in the mid Noughties, I forget which Park Lane hotel’s gilded ballroom hosted it, but I do remember the trays of champagne (there was always a glass of fizz at Julien) and Naomi Campbell performing her power snake moves down the catwalk. I watched Vivienne Westwood backstage at the Old Sorting Office (Tottenham Court Road, 2009) delicately pinning soft, fabric frogs onto the models as they lined up, ready to catwalk. Daisy Lowe trotted out with her pet dog in her arms. In 2012, Lady Gaga opened Philip Treacy swathed in a purple veil; she spent the rest of the show perched on the floor between two front row benches.

Often fashion week is like a very special London open house; Erdem at the National Portrait Gallery, Jonathan Saunders at Tate Britain, Simone Rocha at the Old Bailey, Harris Reed in the basement Tanks at the Tate Modern. At one of his early shows JW Anderson resurrected the old Saint Martins building in Holborn; empty high rises in the city - oh the views! But oh the lift queues. One season Anya Hindmarch brought everyone down into the perfectly preserved but very much shut Aldwych station and turned it into a cafe serving toasties.

There was the time Richard Nicoll had a drinks trolley touring his front row whipping up dirty martinis; the party Mulberry threw in its old Bond street store, where Hot Chip played, the floor shook, Alexa Chung danced with Alex Turner, and the whole place was so trashed they were banned from having shop parties ever again.

Christopher Kane was part of the Noughties wunderkind Saint Martins generation, Louise Wilson MA course protégées that reignited a new wave of London-based talent - vibrant, provocative, striking confections that caught the maximalist mood. After his graduate show he was taken to meet Anna Wintour; Donatella Versace was an early supporter.

The new guard were flush with sponsorship cash, “there was money pouring out of everywhere to do a show. It’s a different ball game now” he says of the post-Brexit landscape.

“I'm so happy that it’s forty years, London should be proud. It’s produced the best talent in the world, the best art education and I hope it continues. But, in dark times things do get better.” Kane’s fashion week mantra for the next forty years of New Gen? “Be more radical, be more different. Never be in the middle, you either want to be loved or hated. Never be in the middle because it's just so forgettable.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News