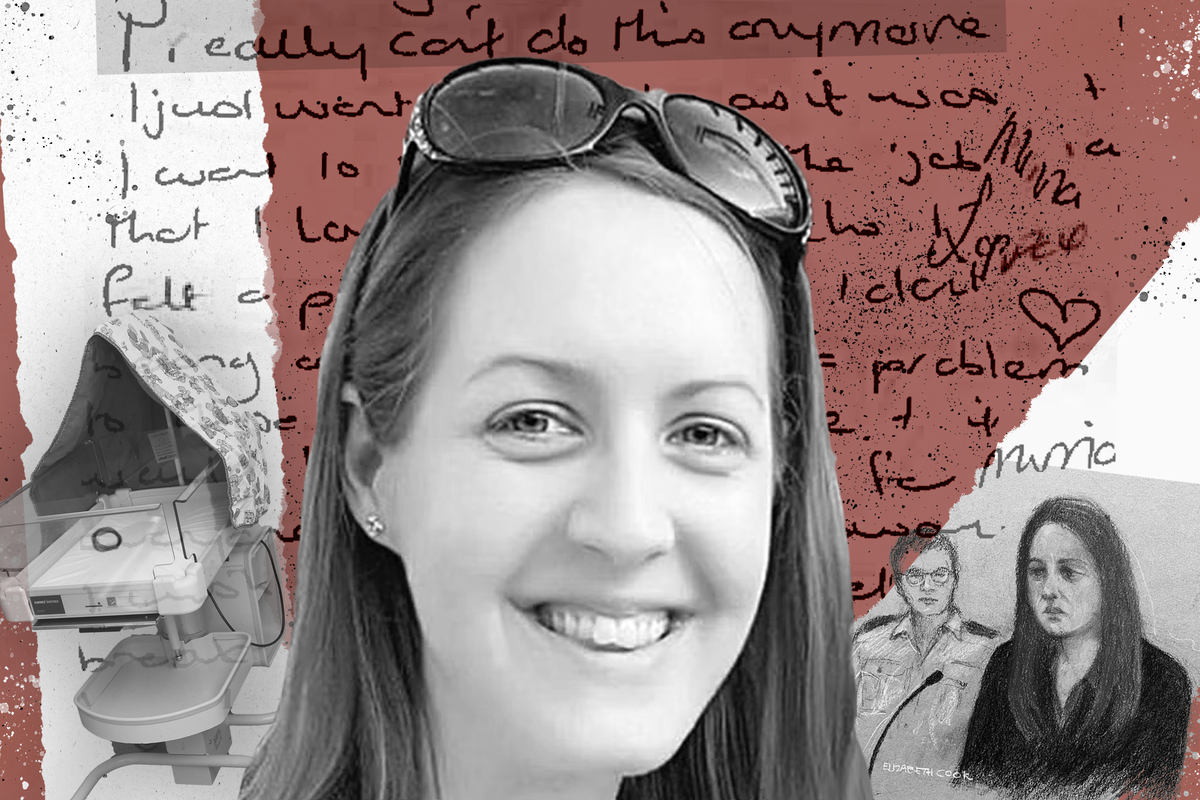

Inside the Lucy Letby trial: Doctors’ desperation, babies’ pain – and the indifference of their killer

This article contains descriptions some readers may find distressing

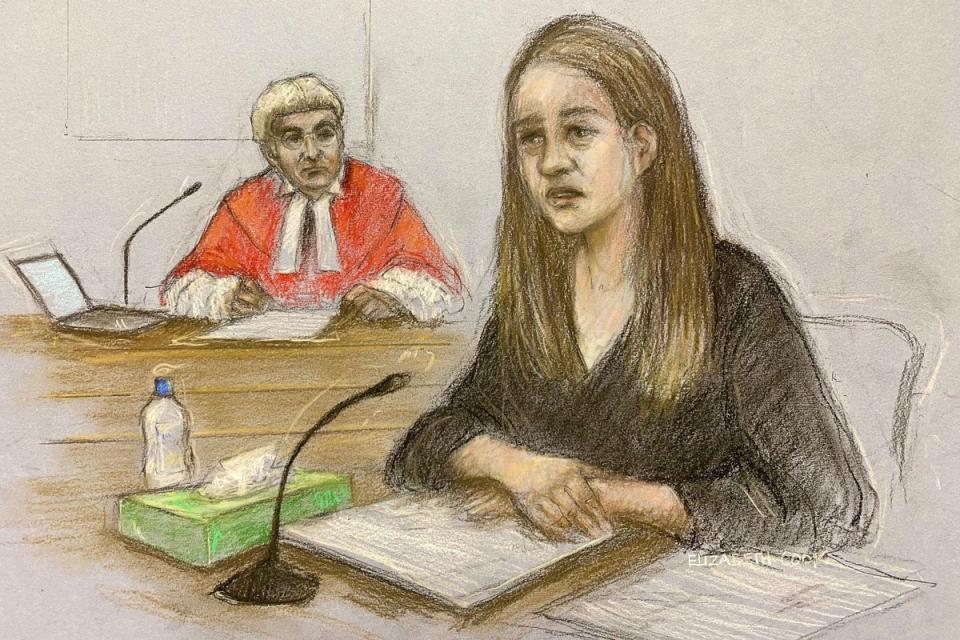

Even though her face was hidden by a screen and her voice a harrowed whisper, those in court could sense that this was a defining point in the Lucy Letby trial.

Dr B was describing the moment a newborn triplet had died in agony – and entirely without reason – just 24 hours after his brother. As she watched the boys’ father lying crumpled on the floor, the paediatrician silently backed his desperate plea to have his one surviving son taken away from the Countess of Chester Hospital.

Because in that moment she saw that despite her own skill, dedication and professionalism, she was powerless against the “mortal danger” posed by the murderous nurse she was unwittingly standing next to. “Even though I didn’t beg”, she told the court, “in my heart I just wanted the baby to leave because I knew that was the only way he was going to live.”

Until that point, much of the trial had been bogged down by the minutiae of medical notes and inaccessible jargon. This made the trial somehow more remote: a legal ping pong between prosecution and defence.

There were exceptions, of course. The jury heard from another doctor so traumatised by a baby’s massive blood loss that he had to take time off to recover, and a nurse who felt another infant’s final heartbeat as she gave desperate compressions with her fingers.

Another crucial moment came when Ashleigh Hudson, a junior nurse on the unit at the time of the killings, gave evidence. She spurned the screens favoured by so many of her colleagues, preferring to see Letby sitting in the glass-panelled dock a few yards away.

Ms Hudson had once implicitly trusted Letby as a friend and fellow nurse. Like so many colleagues in the neonatal “family”, she had been brutally let down by Letby, who slyly worked “in plain sight” to kill the very babies they were all trying so hard to care for.

Letby became so practised a murderer that she routinely created alibis for herself, creating false documents or using WhatsApp and Facebook messages to set up a false narrative to cover her tracks. No one was immune from her vicious betrayal. Not her best friend, a fellow nurse on the unit. Not even the married male registrar she was supposedly in love with.

Just like everyone else in her orbit, they were unwittingly choreographed as she set about “playing God” with the lives of babies so small they could fit in the palm of her hand. In October 2015, for example, a smiling, carefree Letby had joined a throng of nurses on the hen weekend of nursery assistant Jennifer Jones-Key. She resumed her killing spree on her very first shift back, and later used the new bride as cover for a murder.

On another occasion, the killer helped make a banner to celebrate the 100th day of life of a baby girl – and later made the first of a series of attempts on her life, which left the child paraplegic. By the time she was caught, she had murdered seven and tried to kill 10 more. Tragically, even among the survivors there are children, now aged seven or eight, who will spend the rest of their lives needing round-the-clock care.

Letby denied it, just as she denied everything else, but there were suggestions throughout the trial that she derived a sickening pleasure from her attacks. Whether the babies lived or died, the prosecution maintained that she felt a thrill to have caused them to collapse. It was a bonus if she could “help” bereaved parents by preparing a memory box for them – handprints and footprints of their lost baby, a photograph of dead twins laid out in a Moses basket, a condolence card for another baby written in time for the funeral.

Like the serial killer Harold Shipman two decades earlier, Lucy Letby is a narcissist. Shipman, a GP from Hyde, Greater Manchester, got an almost sexual buzz from sitting some of his victims down, injecting them with diamorphine and then quietly watching them die. Prosecutors are convinced Letby felt “excited” by the pain she caused and the way she manipulated the unwitting players – adults and babies alike – in her sinister, depraved drama.

Sometimes the evidence against Letby hit home hard. Midway through an expert’s exposition about a post-mortem X-ray, he highlighted an image of the baby’s liver. There, both shocking and irrefutable, was the damage inflicted on a little boy’s tiny body.

Letby’s most prevalent method of murder was to inject her victims with air. In order to illustrate the horrifying effect it would have, another X-ray image was placed on the screen. This showed the whole profile of a baby’s body, a black line running parallel to the entire length of his spine. It was, said the expert, a line that would have splinted the baby’s diaphragm and made him scream as he struggled to breathe.

References to a baby’s screams in court became almost cursory. It wasn’t until towards the end of the trial that a paediatrician pointed out that such screams – any screams – were unheard of in neonates. Until Letby. And so, suddenly, the pain caused by that line of air became unbearably clear.

Ben Myers KC, defending, suggested many of the babies were teetering on the edge. Some were. And yet, despite that vulnerability, even some of those infants would have survived had they been spared an encounter with Letby. Most of the infants, though, were healthy. One had been due to go home with her parents on the day she was attacked. The two triplets killed in front of Dr B had been naturally conceived and were well from the moment they were born. Like their surviving brother, they were set for a full, healthy lifespan.

It was the horrifying, inexplicable change in fortune that so bewildered medics who again and again found themselves confronted by the unnatural sight of seemingly well babies dying in front of them. As Nick Johnson KC, prosecuting, told the jury: “Of course, no one would have thought that a nurse would have assaulted a child in the neonatal unit of an NHS hospital.”

Mr Johnson appeared to follow a deliberate strategy of stripping away as much emotion as possible from the case so the jury could remain one step removed from the full horror of Letby’s crimes. The number of parents giving evidence was kept to a minimum, with most testimonies coming via statements read out by junior counsel.

When doctors and nurses gave evidence, it seemed that they, too, tried to hold events at arms’ length – discussing this aspirate or that aspirate, this blood sugar level or that sugar level. Often the deeply harrowing collapses of tiny neonate babies were assigned the rather more prosaic medical term “desaturations”.

Anonymity orders granted to the families reduced media coverage of the trial to “alphabet soup”, a feature exacerbated by anonymising many medical witnesses. Among them was the married male registrar Letby was said to have been in love with. He was spared the publicity, despite his role as a key witness and an unwitting confidant of the killer.

For months, Letby herself appeared a sullen, brooding presence in the dock. In the witness box she cried on cue for her barrister, but appeared almost belligerent when cross-examined. It didn’t escape Mr Johnson’s attention that she claimed not to remember some of her victims. He noted, too, that she shed no tears for any of the babies. Those, he said, were reserved exclusively for Lucy Letby.

This article was first published on 21 August 2023.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News