Jah Wobble: 'The cockney is dead and the East End is full of hipsters now'

“The Cockney is dead, long gone, moved out to Essex,” says the great Jah Wobble (real name John Wardle) sitting in second-hand splendour in the otherwise hushed dining room of the Chelsea Arts Club, where the ex-punk is holding court this afternoon. He is extraordinarily good company, whether he’s expounding on his Buddhist faith, the machinations of the music industry (a founding member of John Lydon’s Public Image Ltd, he has collaborated with everyone from Brian Eno and Can to U2 and Sinéad O’Connor), self-obsessed twats (like himself, occasionally), addiction, the legacy of the Sex Pistols or indeed the Cockney diaspora.

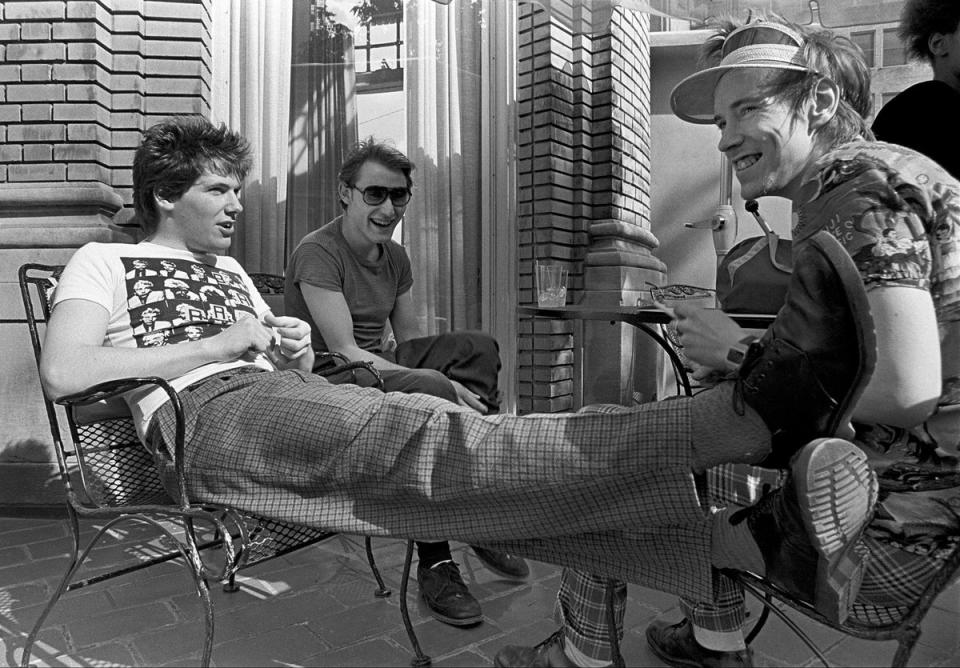

He was there right at the start of punk, was a close friend of Lydon (Johnny Rotten to the great unwashed), saw one of the first Sex Pistols rehearsals and was mooted as a replacement for Glen Matlock when he was unceremoniously booted out of the band. But Wobble knew the chemistry wasn’t right (no one orders him around).

“The Cockney has become a kind of hybrid,” he says. “It’s Essex now. If you want to hear people who talk like me you go to Buckhurst Hill, at the other end of the Central line. Buckers, as they call it. In my family the ones who have done reasonably well have gone to north Essex, and the other lot have gone to Barking and Dagenham. Cockney is done now. I’ve been very influenced by Buddhism, and everything’s impermanent. It all dissipates. Same for the Cockneys.”

We’re meeting today because he has just written a completely brilliant autobiography for Faber, Dark Luminosity: Memoirs of a Geezer. It’s an expanded version of a book that passed me by when it was originally published in 2009 by Serpent’s Tail. This version has additional material as well as a typically illuminating foreword by punk archivist and all-round genius Jon Savage. Unlike many pop memoirs — and, my word, I think we might have almost had enough of them — this one is almost completely unsentimental, quite forcefully honest (there’s alcoholism, a bit of bad behaviour, and an innate distrust of the upper classes), and unremittingly astute. It’s also extremely funny. I read it in several gulps over a weekend last month and couldn’t believe how much fun I was having.

One of the most refreshing things about the book is the way it espouses Wobble’s worldview, an uncompromising refusal to accept what he doesn’t like, doesn’t want, and doesn’t think is right. Talking to him I was reminded of what a good friend said to me years ago about someone he knew: “I couldn’t think that way, but I’m glad someone does.”

And that’s Wobble. He was born in the East End maternity home in Commercial Road. Strict Catholic background. Altar boy. Brother was a priest. Irish roots. The one true faith. A bit of a delinquent (burning furniture in a squat, as you do). Read a lot. Wanted to be a footballer, then a train driver, and fell into music. Loved the sound of Philadelphia, loved bluebeat, Hawkwind, the Faces, the Who, Bob Marley. Didn’t see punk as a commodity. He loved the bass as it was visceral. Loved the frequencies, loved the background resonance. And loved London.

I go back to the East End now and I feel like a ghost. It’s full of hipsters. It’s a shame because we had a good culture.

“The reason I wanted to write the book is because I wanted to document my people, the East End,” he says. “I could already start to feel that it was going to be more like the 19th century than the 21st century. I wanted my sons to know where we came from. I go back to the East End now and I feel like a ghost. It’s full of hipsters. It’s a shame because we had a good culture. I’m a dyed-in-the-wool East Ender and all of my mates were.”

One of the most unusual parts of the book is the passage where he talks about working on the Underground and driving Tube trains after he got clean in the mid-Eighties. It’s told with unflinching tenderness, completely without pride. It’s certainly not the kind of thing you expect to read from a rock star (although I’m quite enjoying the idle fantasy of reading Miley Cyrus’s autobiography — say — and finding out she occupied her time during a fallow period by working on the buses).

“I did the Twelve Steps when I was working for London Transport, at Neasdon depot, the most boring place in the world, and the one I was doing was the fourth step, ‘make a searching and fearless moral inventory of yourself’. This was back in the day, when even people in mass transportation would have a drink of lager. So, you’ve got some geezers over there drinking their Harp, then you’ve got some geezers all gambling, a couple of geezers are off with their mistresses, and one or two blokes doing Open University courses. And I’m there, furiously scribbling away, worried about somebody asking me what I was doing. ‘Oh, I’m just making a searching and fearless moral inventory of myself, actually.’”

Once, at Tower Hill station, via the public address system, Wobble regaled commuters with the deadpan announcement: “I used to be somebody. I repeat, I used to be somebody.”

As we left the Chelsea Arts Club, I was reminded how popular he is, as he was accosted (in a friendly way) by a dozen people who all wanted to say hello and shake his hand. The PR puff for his brilliant book calls him an alternative national treasure and having spent 90 minutes in his company I can only agree. Just don’t get him talking about the Tories. Or the posh. Or hipsters. Or…

Yahoo News

Yahoo News