Jared Kushner is a Know Nothing – not just because he has failed on so many fronts

Jared Kushner has let it be known that based on his understanding of American history, the Republican party platform should be drastically reduced from 58 convoluted pages in 2016 to “a mission statement” that can fit on a wallet-sized card, along the lines of the platform of 1856, “in order to eliminate alienating language”.

Related: This Is What America Looks Like review: Ilhan Omar inspires – and stays fired up

The son-in-law of the president, senior adviser above all senior advisers and de facto campaign manager, has shifted from one earthshaking assignment to the next: chief diplomat to achieve Middle East peace; chief overseer of domestic policy and patron of Stephen Miller; chief of medical supplies in the coronavirus crisis.

Now a self-designated expert in American history, his attempt to echo the party’s first platform is an abrupt effort to smooth over Trump’s alienation of large numbers of voters, to airbrush the president’s offensive and lethal incompetence, and to justify it all by reference to the origins of the Republican party. He is abusing the past to distort the present, in order to control the future. But the past is not as malleable as Fox News.

The symmetries between the past Kushner seeks to exploit and the discreditable present are striking. If there is any resemblance of the Trump mutation of the Republican party to any actual party in the election of 1856 it is not to the Republicans. Nor is it to the Democrats. Rather, it is to the third party in that campaign, the American party, also known as the Know Nothings, who also had a concise platform.

The original American party sought to protect the purity of white native-born Protestants from the first great wave of immigration to the United States, which consisted mostly of the Irish and Germans, and to stigmatize a subversive religion.

“Americans must rule America,” its platform proclaimed. Only native-born citizens should be allowed to hold any public office, federal, state or municipal. Catholics, described in the category of those pledging “allegiance or obligation of any description to any foreign prince, potentate or power”, were to be proscribed.

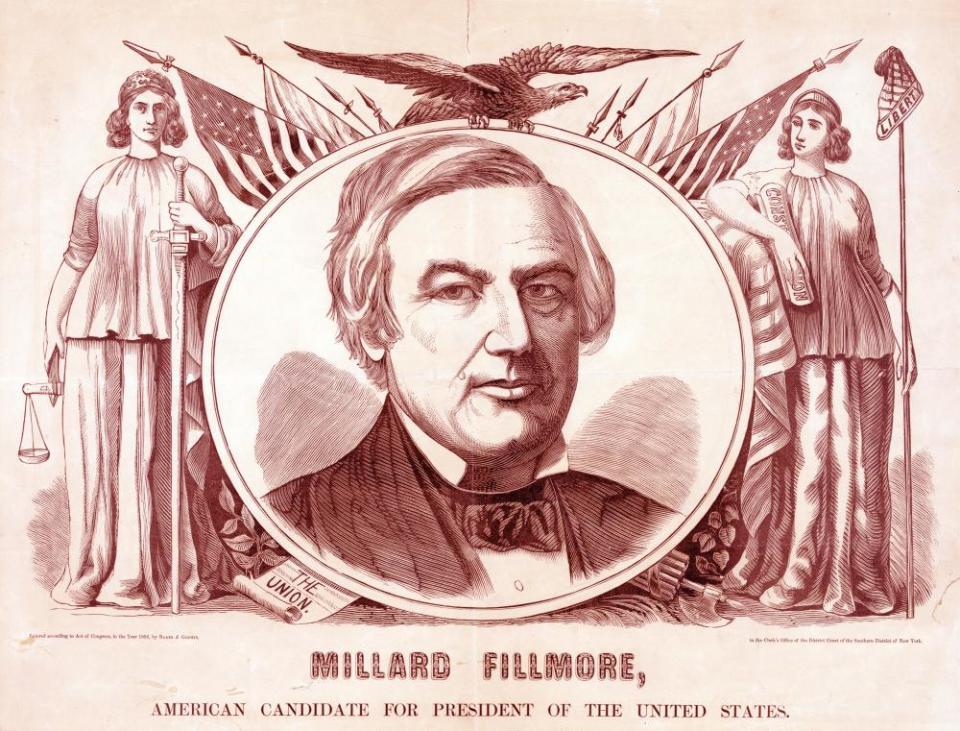

The Know Nothings emerged from the crack-up of the Whig party over the issue of the extension of slavery in the territories. Most regarded themselves as Old Whigs, “conservatives in principle” in the words of their party platform. Their standard-bearer was Millard Fillmore, the last Whig president, a decorous figurehead. The Democrats nominated James Buchanan, a northern man of southern sympathy, a distinguished former senator from Pennsylvania, the crucial swing state.

Abraham Lincoln, a lifelong Whig, forged the Illinois Republican party in 1856 out of a cacophony of contending factions, including radical abolitionists, Whigs, dissident antislavery Democrats and liberal German immigrants. Lincoln despised Know Nothingism.

In 1855, he wrote that if the movement ever won power it would rewrite the Declaration of Independence: “When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read ‘all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and Catholics.’ When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty – to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.”

Behind the scenes, Lincoln worked to undermine the Know Nothings, break up their party and bring some of its former Whig adherents to his new cause. In order to hold together their fragile coalition, Lincoln in Illinois and Republicans nationally advanced the singular goal of prohibiting slavery in the territories.

The Republican presidential candidate in 1856, John C Fremont, was a famous western explorer and senator from California. Both the “Americans” and the Democrats mounted vicious smear campaigns against him: that he was not native-born but of foreign birth, illegitimate and a secret Catholic. “Trial by mud,” his wife Jessie Benton Fremont called it.

Two years later, running for the Senate, Lincoln declared that immigrants who believe in the Declaration of Independence’s precept that “all men are created equal” are “our equals in all things … as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration, and so they are. That is the electric cord in that Declaration that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together.”

The 1856 Republican platform may provide another piece of symmetry to the modern day. Its longest plank listed the trampling of constitutional rights of the antislavery forces in the Kansas territory, including voter suppression, attacks on freedom of the press, instigation of violence, and violence by armed militias.

The Republicans promised to restore the rule of law after the election by bringing members of the current federal administration before the bar of justice for their crimes: “That all these things have been done with the knowledge, sanction, and procurement of the present National Administration; and that for this high crime against the Constitution, the Union, and humanity, we arraign that Administration, the President, his advisers, agents, supporters, apologists, and accessories, either before or after the fact, before the country and before the world; and that it is our fixed purpose to bring the actual perpetrators of these atrocious outrages and their accomplices to a sure and condign punishment thereafter.”

Related: 'What politics is': Sidney Blumenthal on Lincoln and his own Washington life

But the Republicans lost the election of 1856. There were no prosecutions. The early platform stood as a warning of greater danger to come. After Lincoln’s election in 1860, many of those identified in the first Republican platform as the enemies of democracy, presidential advisers among them, would not accept the result and helped precipitate the civil war.

If Trump loses the election of 2020, will “his advisers, agents, supporters, apologists, and accessories” and “accomplices” – including, first and foremost, Jared Kushner – accept the result and its consequences?

Sidney Blumenthal is the author of All the Powers of Earth 1856-1860, the third of his five-volume biography, The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln, and a former adviser to President Bill Clinton and to Hillary Clinton

Yahoo News

Yahoo News