Jenson Button exclusive: There was no disbelief, it was just there - my dad was dead

There’s a restaurant in Santa Monica that I have to pass in order to reach a bike shop I use. I can hardly bring myself to look at that restaurant. I don’t like to think of the last time I was in there.

It was January 2014 and I was in that restaurant having lunch: me, my physio Mikey Collier, Chrissy Buncombe, and a Japanese friend of ours, Yu. We were hanging out, enjoying each other’s company, oblivious to what lay just around the corner.

Mikey’s phone rang, he took the call and it was impossible not to notice the change that came over him. His face fell from relaxed and companionable to grave in the space of a second. Other conversation died and I leaned towards him, looking at him, like, What? What’s wrong?

“JB,” Mikey said, “it’s Richard on the phone. We need to talk outside. He has something to tell you.”

Mikey and I stepped out to the sidewalk where I leaned against a windowsill and he handed me the phone. “Jenson, I’m so sorry,” said Richard. “It’s about your dad.”

Richard and Dad had been out for dinner the night before. After their meal they stopped in for a nightcap at La Rascasse, a bar the mechanics love to visit during Grand Prix weekend.

While in the bar, Richard took a call. It was some bit of business that needed attending to, and he stepped outside to deal with it. By the time Richard had finished and returned to the bar, Dad was gone. There were some guys there they both knew. “Where’s he gone?” asked Richard. Shrugs. “Oh, he just got up and left.”

This wasn’t particularly unusual for Dad. His diabetes meant that he tended to get tired quickly. It was perfectly normal for him to just leave like that. However, when Richard rang to check on him the next morning, he couldn’t get hold of him.

One of Dad’s favourite jaunts was to take his Ferrari down to Italy for the day and meet up with friends for coffee. He’s probably done that - silly old sod’s probably left his phone in the car, thought Richard.

The alarm bells came later. Richard became more concerned with each unanswered call, and so at about 7pm, he pulled on a pair of tracky bottoms and a sweatshirt and set off for Dad’s house.

The house was built on the side of a cliff, and to get to it you had to enter through a front gate at the foot of the incline. That gate was pretty much impregnable. It had been reinforced after a burglary attempt. Once you were inside, there were about 60 steps up to the front door, which was quite a climb. I used to find it hard myself.

When Richard arrived he found Dad’s keys on the outside in the gate, which was odd. Richard was remembering the break-in attempts and, deciding he’d better check to make sure everything was okay, he let himself in and began the climb to the front door.

He found Dad’s body on the steps. There was blood and at first Richard thought that he might have tangled with burglars. Subsequently we’d discover that wasn’t the case, but there was a lot of initial confusion, and after Richard’s wife, Caroline – who’s half-French – alerted the authorities, Richard himself became a suspect; he had to call a lawyer and they wouldn’t let him phone me. In the end he told them, “Listen, I’m going to call my mate to tell him what’s happened. You’ll have to arrest me if you want to stop me. It’s up to you.” And that’s when Mikey’s phone rang.

There was no delayed reaction; it hit me straight away. I put that down to my job, the way I lived, something about the ability to absorb a sudden and shocking turn of events, being able to quickly process matters of emotional intensity. There was no period of disbelief or numbness. It was just there. My dad was dead.

How could it have happened? The answer is that we don’t know for sure. All we have are fragments. And given that the police investigation has ended having drawn a blank, we will never be 100 per cent certain what took place.

We know that Dad returned to his car. But we think that somewhere between La Rascasse and the car he fell and hit his head. As I’ve said, his balance wasn’t the best. In Monaco, the escalators don’t work until you step on to them, and even then they’re not very reliable. Sometimes they don’t go at all; sometimes you’re halfway down and they suddenly shudder into action. They catch a lot of people out.

Maybe Dad, that night, was one of those caught out. Maybe he fell. Certainly when we saw CCTV from the car park, he had blood on the back of his head. There was also a little blood found on the headrest of his car. The most logical explanation is that he fell foul of the escalators.

Nevertheless, he made it to Cap-d’Ail, and at about 3am arrived at his house. Again, we don’t know how it happened, but what we do know is that having let himself in, the gate shut behind him and his keys were on the other side of it. Now he had a problem. The only way to open the gate was from inside the house – you buzzed it open. But he couldn’t get into the house because his keys were on the outside of the secure gate.

There was a little granny flat, a tiny one-room apartment, halfway up the stairs, and judging by some blood on the pillow he lay down in there for a bit. Then, for whatever reason – perhaps because he needed insulin and had a brainwave about getting in – we think he decided to have another crack at gaining entry to the house.

Wearing his shirt, underwear and socks, he climbed the remaining steps, probably using the torch on his phone to light the way. Whatever the brainwave, it didn’t work, because he had turned away from the door and was returning down the steps when he slipped, fell forward and hit his head for a second time. This one proved fatal.

The days after the phone call were a blur. We returned to Monaco, joined the rest of the family, tried to keep things together as we concentrated on organising the funeral, operating in a kind of daze, wanting to wake up from this awful dream.

At the same time I had a sore spot on my leg. I didn’t know how, why and where it had first appeared, but it was like a little painful area on my knee. Didn’t think much of it. One night we had an evening out – a mad night with alcohol a catalyst for our tears – but the next morning I woke up and my leg was in agony.

I called my mum who was in the same hotel, the Metropole. “Mum, can you come up to my room, please? I think there’s something wrong.” I was looking at my leg as we spoke, seeing for the first time how swollen it was. Moments later she was at the door. I answered it and promptly collapsed.

Somehow I’d picked up blood poisoning. They thought it was from swimming in the sea in Hawaii. I’d cut my foot and my body didn’t have the strength to fight the infection. My mum called the rest of the family to the room. I fainted again.

The next thing I knew I was being carted off to hospital and all sorts of drips were going in me. They were taking it seriously. If the infection’s reached the bone then that’s bad, I was told. Like, amputation bad. So that was a sweaty few hours, while they ascertained whether the poisoning had indeed reached the bone. It hadn’t and I was free to leave, except I couldn’t walk because the pain was so bad; every time I moved the poison would shift.

In the end I made it to Richard’s house, and that’s where I stayed for the next few days, sorting out funeral arrangements. The pain was intense – like nothing I’d ever experienced, before or since; to keep it at bay I had to raise my leg above the level of my head. Showering was agony. Using the toilet, oh my God.

I could hardly walk and yet there was no way in the world I was going to shirk my responsibilities as a pallbearer. Just you try and stop me. I gritted my teeth, expecting tremendous pain. But I suppose certain emotions take over; the body assumes control to makes sure you get through it. That same internal autopilot helped me deliver the eulogy – the hardest, most painful speech I’ve ever had to give.

Dad would have loved the fact that Prince Albert of Monaco was in the front row at his funeral. Loved it. He would have loved the fact that his funeral was at turn one of the Monaco Grand Prix; he would have been thrilled to see all the people who turned up that day.

I’m not sure about the choice of funeral vehicle, though. He always said he wanted to slide into his grave, locked up, sideways in a cloud of tyre smoke. What he got instead was a Volvo estate.

F--k-sake, Jense.

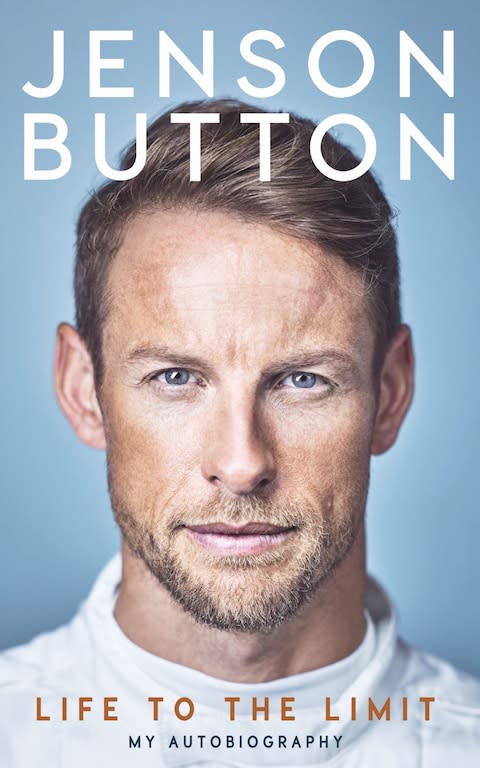

Edited extracts from Life to the Limit by Jenson Button which is published by Blink (£20). To order your copy for £16.99 plus p&p call 0844 871 1514 or visit books.telegraph.co.uk

Yahoo News

Yahoo News