Joan Baez: ‘It feels good to have changed the world’

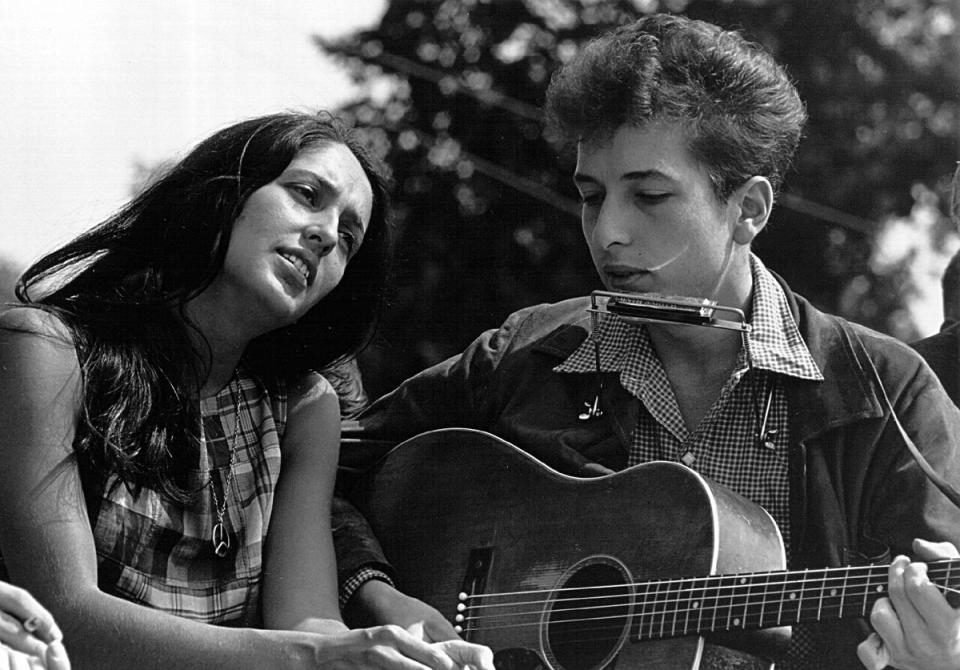

Joan Baez was 28 years old and six months pregnant when she walked out on stage to headline Woodstock in August 1969. It was late enough that Friday had become Saturday, so she greeted the tired and tripping masses with a bright: “Good morning everybody! Thank you for hanging around.” Over the next hour she held them spellbound with songs written by the likes of Willie Nelson, The Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan, having helped to usher Dylan into the limelight just a few years earlier when she invited him on stage with her at Newport to duet on the protest anthem “With God on Our Side”.

Only one song, “Sweet Sir Galahad”, was a Baez original. “It’s the only song I’ve ever written that I sing anywhere outside the bathtub,” she announced over the mud. “Because I’m just smart enough to know that my writing is very mediocre.”

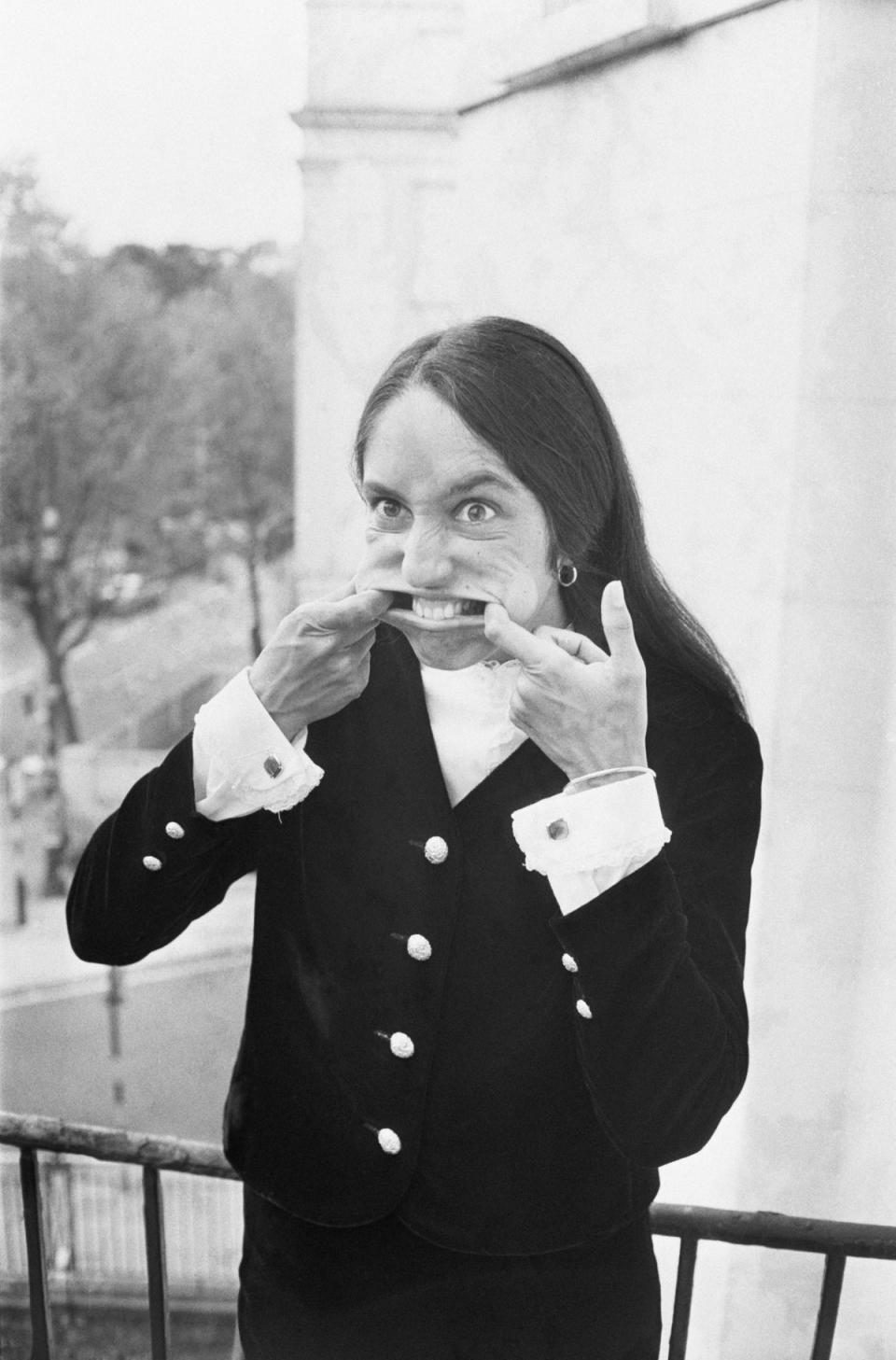

Baez no longer thinks her writing is mediocre, but this revelation came to the 83-year-old only recently. “I started getting more confident about three months ago,” she says, with a musical laugh that lets me see the diamond embedded in gold in one of her teeth. It’s easy to think of Baez as the original long-haired folkie, but these days, with her silver pixie cut and twinkling tooth, there’s a touch of the rock’n’roll pirate about her. “People said to me so many times, ‘But they’re good songs!’ So I went back and listened... and they’re good songs!”

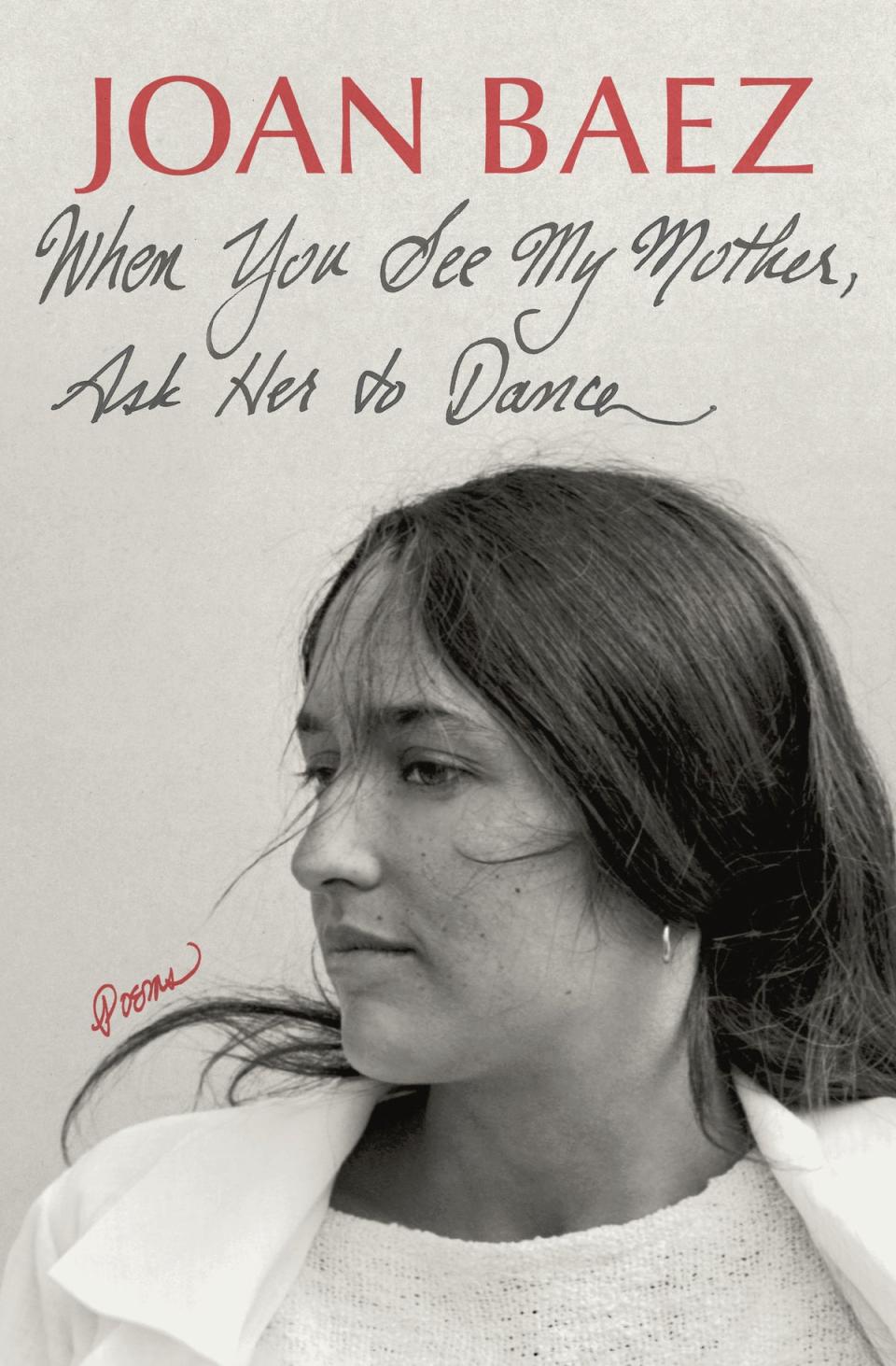

Baez released the last of her 25 albums in 2018, and retired from touring the following year. Today, she’s at her rural home in Woodside, outside Palo Alto in northern California, speaking to me over video call from in front of an antique wooden organ in her kitchen, surrounded by copper pots and candles. She is about to publish her first collection of poetry, When You See My Mother, Ask Her to Dance, which offers further evidence that Baez’s vivid, expressive soprano and unerring ability to fuel her activist politics with song are far from the sum of her talents.

Her poetry, drily funny and wise, mixes autobiographical musings with sketches of contemporaries such as Dylan, Judy Collins and Leonard Cohen. In “Jimi”, she recalls watching Jimi Hendrix at both Woodstock and the Isle of Wight Festival shortly before his death, and describes the experience as like witnessing “a magnificent natural disaster, like a f***ing volcano”. To me, she laments that she didn’t spend more time with him off stage, saying: “I wish I had hung around and knew him a little better.”

Elsewhere, as in the opening “Goodbye to the Black and White Ball”, she draws candidly on her experiences in therapy, painting a picture of herself as “chronically anxious, insomniac, promiscuous, multi-phobic, depressed, hyper-vigilant, and, luckily, immensely talented”. She says putting pen to paper helped her to process emotions she’d struggled with for years. “I reached a point in deep therapy where I could kind of think, ‘Oh, there’s a way through this,’” she says of writing the poem. “When people ask me now, ‘What’s your greatest achievement?’ I would say getting through that tunnel.”

Baez was born on Staten Island in 1941, grew up in northern California, then moved with her family to a suburb of Boston in the late 1950s where she got her start singing in coffee shops. In 1959, a friend took her to the first Newport Folk Festival, where she performed in front of 13,000 people and became a star almost overnight. She was eighteen years old, barefoot with a rose in her hair, singing timeworn spirituals in a bewitching high soprano. Her self-titled debut album, released in 1960, sold more copies than the work of any female folk singer before her.

After recording primarily traditional ballads on her first three albums, Baez found even greater success interpreting contemporary songs such as Dylan’s “It Ain’t Me Babe” and The Band’s “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down”. “There was insane talent,” she says now, growing wistful. “In that time period there was Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez, Peter, Paul and Mary, Jimi Hendrix, all of them! People ever since then have wanted that level of creation back. You can’t recreate that volume of talent, and some of that must have been triggered by the times around us, which were charged.” Baez was always tuned in to that energy, and as her fame grew she inspired a generation of young people to pick up guitars and engage with civil rights, the environment and the anti-war movement.

When she first met Dylan, at Gerde’s Folk City in Greenwich Village in 1961, she was the “Queen of Folk” and he was a mere young pretender, or as she later wrote, “the unwashed phenomenon”. They fell in love and were together for a couple of years (her best-known composition, 1975’s “Diamonds & Rust”, is about their relationship) until Dylan left her, and the folk scene, behind when he plugged in to electric rock’n’roll. By then, their statuses had reversed. “I think that his fame happened so fast, and it was so huge, that I kind of got lost in the shuffle,” she tells me now. “I remember a kid came up to me – this was the worst of it, when I really didn’t exist to any of them – some kid came up to me in Germany in a lobby and said, ‘Oh, Miss Baez, can I have an interview with you? Bob wouldn’t give me one.’ I said, ‘F*** you!’ It was horrible. It was really awful.”

In her poem “Portrait”, Baez recalls the magic of their early years together, and writes of Dylan as a “brilliant kid” scribbling down “thought-dreams”. Baez says his obvious genius as a songwriter “was a lot of the charm” that sparked their relationship. “I talk about stuff, pouring out of me, that I don’t know where it’s coming from. I believe that’s true of Bob,” she says. “Watching him, his hand was going a mile a minute, and he was smoking, and he was picking at his hair, and that stuff came out brilliant.”

Such is the fascination with this period of her and Dylan’s life that the story is currently being made into a film, A Complete Unknown, by the director James Mangold. Timothée Chalamet will play Dylan, with the Top Gun: Maverick actor Monica Barbaro as Baez. “It seems sort of silly, but I don’t know,” says Baez when I mention it. “Maybe people will enjoy it and learn something from it.”

She reached out to Barbaro when she heard about the film, to offer a few words of advice. “I just talked about my dependence on Bob, and how I always felt below him,” she says. “That he was ‘the dude’, and I was kind of...” She trails off. “It’s true! I mean, I was so infatuated with him and the music that I was...” She opens her mouth and gawps, eyes skyward. “I was always looking up like that, so I thought she would probably benefit from that kind of explanation.”

During their time together, Baez got Dylan heavily involved in the civil rights movement she was so committed to. In 1963, they sang at the March on Washington from the podium where Martin Luther King Jr delivered his “I have a dream” speech. Having seen that movement bring about such monumental change, Baez remains passionate about the potential of activism to transform the world. “We can’t negate what happened just because it went backwards,” she says. “Especially now, when we’re fighting uphill against an avalanche of evil, sadism and bullying.”

She speaks about the causes close to her heart with real conviction, but with an irreverence that’s a far cry from the early years, when she was characterised as a pious do-gooder. As a lifelong environmental campaigner, she notes that witnessing the reality of climate change has left her “terrified”, but she faces it with a dark and uncompromising sense of humour.

“No matter how many of us tried to make people aware, it’s caught up with us,” she says. “Mother Earth is in a rage, and you really can’t blame her. I don’t want to have my life dictated by fear, but sometimes it’s just overwhelming to wake up at night and think ‘What, if anything, is there going to be for my granddaughter?’” (She has a son, Gabriel, with her ex-husband David Harris.) “Possibly nothing? We may be gone. I have a really black joke that I made up: we will be lucky if we get eliminated by climate change, because then Trump won’t have time to set up death camps. It’s pretty awful, but it’s true.”

When we got arrested for aiding and abetting draft resistance, we were walking and singing into the paddy wagons

Baez has never stopped speaking out about the issues she believes in, and has borne witness to quite staggering social upheaval. In 1989, she was an outspoken supporter of the Czechoslovakian opposition leader Václav Havel; her performance in Bratislava has been cited as the “last drop” in the cup that overflowed into the Velvet Revolution, which peacefully overthrew communism in the country.

By then she had been dedicated to a philosophy of non-violence for over two decades, having opened a school, the Institute for the Study of Nonviolence, in Salinas, California in 1965. She married the prominent anti-war protester Harris in 1968 (they divorced in 1973), and once went to jail for 11 days for participating in a sit-in at a military induction centre to protest against the war in Vietnam. As we speak, police on university campuses are heavily cracking down on students protesting against the war in Gaza. Baez wishes she could be there. “Hats off to them,” she says of the protesters, but she has notes. “I wish they had nonviolence training, because the shouting and screaming and ‘F*** the cops’ or whatever does not help your programme.”

She’s admirably staunch in her belief that nonviolence must be absolute, even if her memories of her brief incarceration sound somewhat idealised. “When we got arrested for aiding and abetting draft resistance, the police would come, and they wouldn’t start beating anybody over the head because we were walking and singing into the paddy wagons,” she tells me. “That’s very different from shouting at the pigs and starting the fight up.”

By the 1980s, the music scene was becoming less political, and Baez found herself without a record deal. For a time she retreated to northern California, but once again events that would revolutionise society weren’t far away. For a few years in her early forties she dated the Apple founder Steve Jobs, who was then in his mid-twenties, and they remained close. Before his death in 2011, she asked him how it felt to have changed the world.

“He said, ‘Good!’” she reports with a laugh. “We were an odd couple. I mean, I didn’t understand anything he was talking about, ever. I don’t know what his fascination was with me, but we really couldn’t have a conversation on an equal level. He was about tech, and I was about music. Then he bought a grand piano, a Bösendorfer, which makes Steinway look like nothing. He called up and he said, ‘Could you teach me how to play the piano?’ So I went over and said, ‘This is middle C,’ but we didn’t go beyond that. There was nothing in that room but the piano. It was insane.”

One could ask Baez the same question she once asked Jobs. How does it feel to have changed the world? She laughs modestly. “I guess I don’t spend much time thinking about it.” Then, after a moment, she adds: “I think if I could include the people, like the Havels and the Kings, that I’ve been lucky enough to meet, if you put us all in the same package, then it feels good to have changed the world.”

‘When You See My Mother, Ask Her to Dance’ is out now in the US, published by Godine. It will be published in the UK on 13 June

Yahoo News

Yahoo News