Jupiter Probe Gets by with Blender's Worth of Energy

NASA's Juno probe has traveled nearly 1.8 billion miles (2.8 billion kilometers) through space to reach Jupiter and study the planet's history, yet this impressive probe needs only about the same amount of power as a blender, according to NASA.

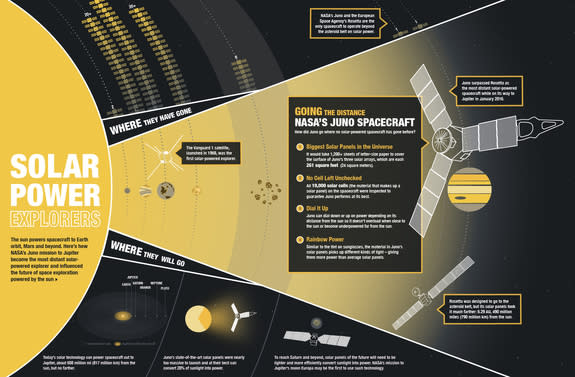

After a five-year journey, Juno is scheduled to reach the Jupiter system on July 4. The probe is expected to get closer to the Jovian giant than any other mission in history. In addition, Juno is now the world’s "most distant solar-powered spacecraft," NASA said.

Jupiter is located about five times farther from the sun than Earth and receives about 25 times less sunlight. But because of Juno's extremely low power consumption, the probe can stay alive by collecting sunlight using three large solar arrays that extend from the spacecraft's hexagonal body. [Photos: NASA's Juno Mission to Jupiter]

In a web series, called "Crazy Engineering," produced by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Mike Meacham, a mechanical engineer at JPL, discussed Juno's low power needs and the science behind the probe's solar arrays.

In order to generate enough power to properly operate Juno at such a great distance from the sun, NASA engineers designed solar arrays with incredibly vast surface areas. Each of Juno's three solar arms is about 29 feet (8.8 meters) wide. On Earth, they would be able to generate about 14 kilowatts of power all together, the video said. But out at Jupiter, they generate only about 500 watts of power.

With its three solar arrays extended, Juno measures about 65 feet (20 meters) across. In order to fit inside the nose cone of the launch vehicle, the three solar arrays are broken into four segments, connected by hinges that allow for easy folding prior to launch.

With the spacecraft packed up into the launch vehicle, the cells of the solar arrays were hidden from the sun — Juno's power source. This made deploying the spacecraft particularly interesting for the NASA team, as the solar arrays needed to extend properly after launch, in order to absorb enough energy from the sun. Since then, the solar panels have remained in sunlight, and will continue to do so through the end of the mission, in February 2018.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Editor's Recommendations

One-Week Countdown Begins for Juno Mission's Daring Arrival at Jupiter

Amazing! Jupiter Probe and Blender Run On About Same Power | Video

Juno Spacecraft's July 4 Jupiter Arrival: Complete Mission Coverage

Copyright 2016 SPACE.com, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News