Just election in Turkey not possible, says imprisoned Kurdish candidate

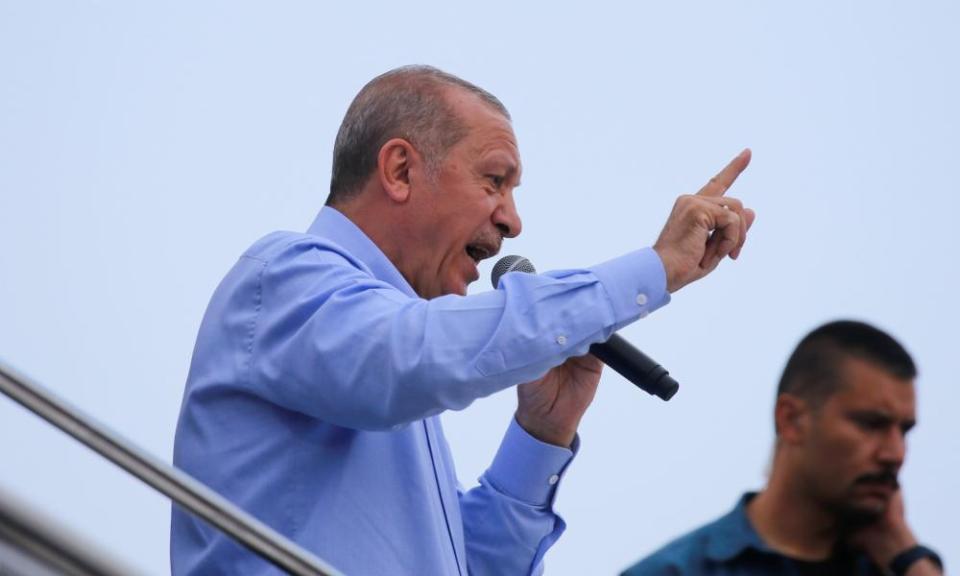

Dressed in a suit and burgundy tie, Selahattin Demirtaş addressed his supporters through Turkey’s state-run TV. He urged citizens to vote against one-man rule by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his ruling party, the AKP, whom he described as bullies.

But there was one difference between all the other presidential candidates and Demirtaş, once dubbed the Kurdish Obama and leader of a persecuted leftwing party focused on Kurdish and minority rights.

He was addressing his supporters from his cell at a maximum-security prison in Edirne, where he is standing trial over alleged terrorism offences.

“I am answering your interview questions from prison; how can it be fair?” said Demirtaş in an interview with the Guardian, conducted through his lawyers. “Because of the state of emergency, fear has taken over the population. Erdoğan conducts a campaign with the whole power of the state, media almost fully under his order. A just election race is not possible.”

Turkish citizens vote on Sunday in arguably the most crucial presidential and parliamentary elections in the republic’s modern history. Kurdish voters, who make up 15-20% of the population, have emerged as kingmakers once again and could end the AKP’s 16-year parliamentary majority and bruise Erdoğan, Turkey’s most powerful politician.

The winner of the presidency will assume sweeping new powers narrowly approved in a referendum last year. Reliable polls are rare in Turkey, but on average they appear to predict that Erdoğan will win the vote in a second-round contest against Muharrem İnce, the opposition candidate from the secular Republican People’s party (CHP).

The parliamentary elections are more complicated, with two main coalitions facing off against each other. Erdoğan’s AKP is allied with the nationalist party, the MHP. The opposition has united in a grand coalition, which includes secularists, Islamists and breakaway nationalists, to improve its chances of picking up parliamentary seats.

Demirtaş’s Peoples’ Democratic party (HDP) is not in any alliance, and therefore needs to get at least 10% of the national vote to enter parliament.

“There is an immense will for change in Turkey,” he said. “People are fed up with the tyranny of the AKP government and see the elections as an opportunity to express it.”

Few can accurately predict who the Kurdish-majority areas will turn out for in the election, where votes are generally divided between Demirtaş and Erdoğan’s parties.

Many are angered by Erdogan’s alliance with hardline nationalists who want a military and security response to Turkey’s Kurdish rights movement or its separatist insurgency. They are also unnerved by Erdogan’s military forays into neighbouring Syria, where earlier this year he ordered a campaign into the majority-Kurdish enclave of Afrin.

The offensive was publicly aimed at dislodging Kurdish militias in the area, but opponents of the government say it has a darker purpose of engineering demographic change in the region.

Others say Kurdish voters are likely to reward Erdoğan for the calm that has prevailed in the country’s south-eastern region. There was renewed violence in the area between 2013 and 2015 after the collapse of the peace process but this dwindled over the last two years amid a security-oriented response by the government.

Erdoğan’s rhetoric, that Kurds and Turks are united by faith and under one nation, has remained unchanged, but he has pursued a second track of vilifying the HDP as terrorist sympathisers, and the government has arrested hundreds of party cadres, mayors and MPs, including the two chairs of the party.

“The security policies in the cities, the arrests of the MPs Kurdish people vote for, the mayors put in jail, the newspapers and TVs were shut down,” said Ayhan Bilgen, an HDP MP and spokesman. “Therefore the Kurdish people will give a veto [against Erdoğan] as their answer in this election. Policies to date do not comprise any positive expectation or hope for the coming period.”

Fahrettin Altun, an expert at SETA, a thinktank with ties to the government, said Kurdish voters would back Erdoğan. “The main issue for them is peace in the region, not in the narrative,” he said. “The PKK is not in the south-eastern region of Turkey at the moment and that’s a very important issue which is sometimes not being able to understand by outsider analysts. But the people living in the south-eastern region are very happy with this process.”

There are signs Erdoğan is increasingly fearful of losing votes to the HDP. He was surreptitiously filmed at a party meeting in Istanbul urging supporters to do “special work” to defeat the HDP, in what was interpreted by some observers as urging election fraud and voter intimidation.

On 16 April 2017 Turkish voters narrowly approved a package of constitutional amendments granting President Erdoğan sweeping new powers.

The amendments will transform the country from a parliamentary democracy into a presidential system – arguably the most significant political development since the Turkish republic was declared in 1923.

Under the new system - which is not due to take affect until after elections in June – Erdoğan will be able to stand in two more election cycles, meaning he could govern as a powerful head of state until 2029.

The new laws will notionally allow Erdoğan to hire and fire judges and prosecutors, appoint a cabinet, abolish the post of prime minister, limit parliament’s role to amend legislation and much more.

The president's supporters say the new system will make Turkey safer and stronger. Opponents fear it will usher in an era of authoritarian one-man rule.

The opposition candidates for the presidency have courted Kurdish voters, saying they would put Kurdish rights issues in parliament for a vote and would support previously lightning rod issues such as Kurdish-language instruction in schools. All of them called for Demirtaş’s release from jail during the race for the presidency.

For Demirtaş, in his prison cell in Edirne, the evidence of oppression is all too clear in the arrests of him and his colleagues. He has used his 10 minutes of phone calls a week with his wife to conduct virtual rallies, and his image at his desk in prison, cup of tea nearby, smiling alongside a pile of books, has energised supporters.

“It symbolises the anti-democratic practices and the oppression on all fronts including the judiciary by the Erdoğan and the AKP government,” he said of his presidential run. “It is also [the] Erdoğan government that manages the process that leads to the arrests of me and thousands of my friends unjustly and lawlessly for political reasons.”

He added: “Turkish society is strong and determinedly walking towards democracy. Turkey does not consist of Erdoğan.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News