Stab her, your friend said, and you did. I survived – but you scarred my life

You couldn’t have been much older than my 14-year-old grandson is now, when you stabbed me in the neck with a screwdriver. That was 10 years ago, and I’ve often wondered what happened to you. The last image I have was of a skinny kid running down the road with my red handbag – which looked faintly ridiculous.

You never spoke, but the other boy, the bigger one who was egging you on, urged “Stab her, stab her” almost like a dare. Was it a test to allow you to join his gang? If it was, I wonder where that took you – to more attacks, moving from a screwdriver to a knife, from mugging to murder, to prison? Or to you being the one “blooding” new recruits, or a victim of violence yourself? Perhaps you managed to take a different path to the one your teenage self was heading down and feel regret or remorse. Maybe you’ve simply forgotten what you did that night. I haven’t.

While I was being stitched up in intensive care, you or your mates were playing on my phone, had already used my bank cards to steal over £1,000, had my house keys, address, driving licence and other personal effects. The red handbag was found dumped a day or so later but I never used it again.

Thanks to the professionalism of paramedics, the kindness of strangers and the skill of the doctors I didn’t die and I have only a small scar that is barely visible. That’s on the outside, but on the inside is something else. The fear inside me takes a lot of patient unravelling, like a piece of rope that inexplicably tangles into a tight knot.

It comes when I’m walking along a street in the dark, when I’m in an empty train carriage, when I see a couple of youths hanging about. I avoid alleyways and subways, eye contact and arguments, politely decline evening invitations and have sobbed, a shaking wreck after being startled by an innocent jogger or someone walking behind me. After the attack, I would run the short distance from the bus stop to my home with tears pouring down my face and heart pounding. Eventually I moved away.

I am wary of dark places where people like you can hide and pounce, curse myself for not being stronger and braver to fight back, ask myself over and over again what I could have done to avoid being stabbed and always come up with the same answer – nothing.

Were you frightened when that boy said 'Stab her, stab her'? Was your mother too frightened to ask where you were?

The police were supportive, efficient and kind. Over the course of several days they drove me round in an unmarked car to places where gangs and young offenders were known to hang out. At the police station my injuries were photographed and I was shown ring binders full of page after page of photographs of possible suspects. Young men and youths who could have been in a football club or school photo – but the images just reinforced my sense of vulnerability, knowing that so many people thought capable of such an attack were on the streets.

A board at the end of the road where it happened appealed for witnesses, as did the local paper, but no arrests were made. CCTV footage of cash withdrawals made with my stolen cards yielded nothing but images of a person whose face was concealed by a hood.

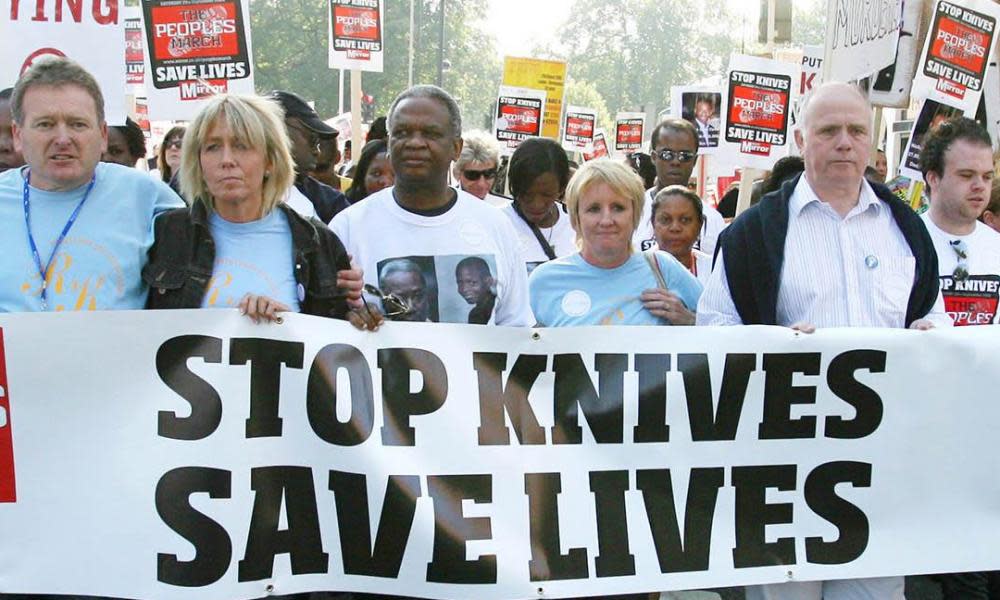

Politicians and police argue over the policies and practices that are to blame for the shocking rise in violent crime that has claimed so many lives this year. Distraught mothers and devastated communities plead for an end to the stabbings and shootings while another slew of initiatives are announced. Newspapers, commentators and experts offer advice, analysis and condemnation, but through a prism that distorts this as a crisis affecting predominantly young, black people in London, and caused at least in part by gang culture.

This makes it all too easy to think the problem is restricted to a particular community, culture or area. There is still, albeit unspoken, a view that if gangs are fighting each other, then it’s not anything for the rest of us to worry about. That has disturbing echoes of the bizarre notion that the Krays and their ilk actually kept crime under control and their neighbourhoods safe.

Ten years on from my attack, weapons are more deadly and readily available, social media more prevalent and pernicious; and too many people have been killed and maimed, with families and lives destroyed. Tougher sentences for carrying a knife wouldn’t have stopped a boy with a screwdriver. There can hardly be a more painful platitude for victims and their families to hear than that they were “in the wrong place at the wrong time”.

I now have a deep-rooted fearfulness that was never apparent before I was stabbed, but the spate of violence on the streets of London helps to breed a collective and wider fear that has terrible implications. It stops people intervening in antisocial behaviour, and instils fear of retribution if you raise concerns about domestic abuse, child neglect or disruptive neighbours, or want to blow the whistle on your employers or colleagues. Fear at a primal level keeps us alive, but it’s also what allows us to avert our eyes from bad stuff.

Fear also stops adults challenging children, particularly when those children are bigger and stronger than them, when there is no alternative but to live, go to school and walk the same streets as the bad kids. Fear makes children think they need to be armed, to do what others urge them to do even though they know it’s wrong.

Were you frightened when that other boy told you to “Stab her, stab her”? Was your mother too frightened to ask where you were that night, or why you’d suddenly got money or new things? Have you got children of your own now, and do you ask them those questions?

When I spoke to the Guardian after my attack, I said I wanted to know why you stabbed me after I’d already handed over my handbag. Ten years on, I still don’t know – do you?

• Jo Phillips is a journalist and former political press officer

Yahoo News

Yahoo News