Kids have a right to water in US schools, but does that water make the grade?

Christina Hecht remembers how water made its way into school lunch law because the process was unusually easy. Back in the mid-2000s, a researcher toured school cafeterias in California and wondered, “What are these kids to do if they want a drink of water?” said Hecht, a policy adviser at the University of California’s Nutrition Policy Institute.

At the time, 40% of the state’s schools failed to offer free water in their cafeterias. That fact eventually reached the then governor and former bodybuilder Arnold Schwarzenegger, who moved to pass SB 1413 requiring schools to offer free, fresh water during mealtimes. Advocates then used California’s example to convince US senators working on 2010’s Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act (HHFKA) – a federal package setting nutrition standards and food funding for public schools and childcare centers – to add drinking water to that legislation, too.

Just like that, water was on the menu nationwide – although scattered and sometimes conflicting data make it difficult to assess how well that legislation has actually worked. A 2016 study by researcher Erica Kenney and her colleagues found that half of middle and high schools in Massachusetts failed to meet both federal and state policies related to drinking water access. However, a 2019 national study conducted by the US Department of Agriculture found a 95% compliance rate with the HHFKA’s potable water mandate among 1,257 sampled schools.

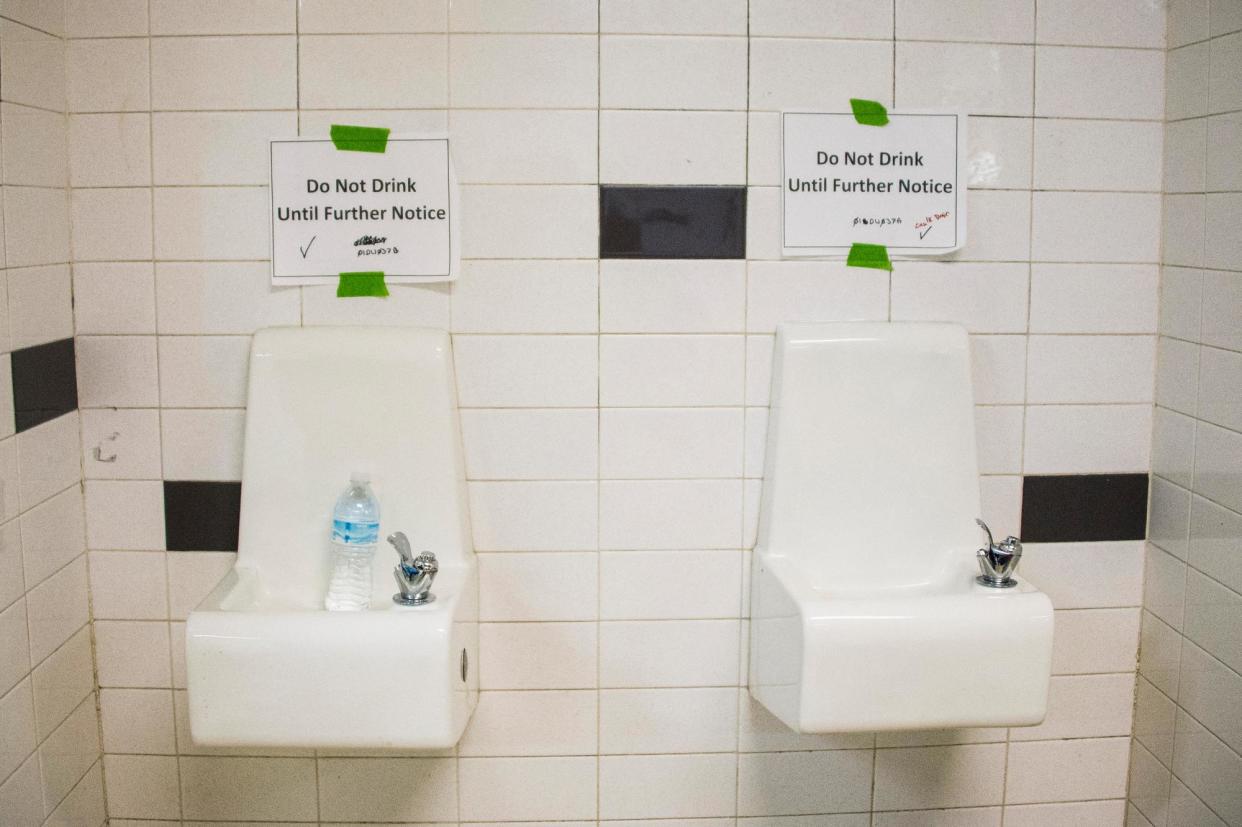

Yet experts say that 14 years after the passage of the HHFKA, many schools are still falling short of its potable water requirement. There’s no federal standard for how schools must address potable water access. So states have been left to figure out how to improve it on their own, leading to a patchwork of water availability and policies. Many school and daycare buildings also contend with elevated lead levels in the water issuing from their taps, thereby failing to meet the legislation’s potable requirement, too. That leaves significant gaps in what researchers call “effective access” to safe water for kids on school grounds, which has health consequences: for instance, under-hydrated children are less likely to be able to concentrate or perform optimally.

Kenney, who studies childhood nutrition at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, says schools use various strategies to get free, potable water into the cafeterias and classrooms where kids eat. Some purchase office-style water coolers. Others offer bottled water. Some add filtered bottle-filling stations to existing water fountains. Still others place cups and pitchers on cafeteria tables.

Then there are schools that haven’t yet implemented changes. Although the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), which oversees the school lunch program, allows nutrition directors to use general lunch funds to pay for low-cost cups and pitchers, administrators have to get creative to fund pricier dispensers, bottle fillers or new fountains – sometimes moving money from wellness or athletic programs or asking parent-teacher associations to fundraise.

The USDA survey seems to indicate that most schools have adequately navigated this terrain. However, that study partly relied on a checklist on which nutrition directors specified whether there was a fountain, free bottled water, a cooler or a pitcher in or within 20ft of cafeterias. According to Hecht, such a format – which does not leave space to include important additional details – fails to ask about the condition of those water sources or the water’s quality. In instances where students have participated in surveys, they have complained of dirty, broken fountains with poor flow and unappealingly warm water.

And while the USDA data identifies the water being served at lunch as “potable”, that doesn’t mean schools are testing it for lead contamination. In fact, lead is widespread in the ageing pipes of schools and childcare centers across the country and, as a result, itis often found in drinking-fountain water. A 2022 study found between 13% and 81% of 5,688 sampled schools in seven states had lead levels in excess of 5 parts per billion (ppb) as recently as 2018, and 82% of schools in New York state had one or more taps dispensing water with lead over 15ppb in that same year. For reference, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends 1ppb as the highest allowable amount in school fountains.

The agencies we expect to protect children at school and at daycare simply put blinders on regarding this issue

Cori Bell of the Natural Resources Defense Coalition

With many schools reporting fountains as their primary source of water, the Guardian asked the USDA how it ascertained that these were lead-free. In an email, a spokesperson responded that “standards for potable water, which is drinking water that is safe for consumption, are regulated and enforced by the Environmental Protection Agency”. The EPA, for its part, claimed in a spokesperson email that it “does not have the authority … to require schools and childcare facilities that are not regulated as public water systems to take actions to remediate for lead”.

Such responses from federal agencies are a pattern, according to Cori Bell, a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Coalition (NRDC). She said: “They all throw up their hands and say, ‘It’s not my job to give kids clean drinking water.’”

Without clear federal guidance or oversight, states address lead problems with their own highly varied protocols. Twenty-three states, including Nevada, Mississippi, Oklahoma and Michigan (home to the Flint water crisis), have no laws requiring lead testing in schools. Others, such as Illinois, have laws to test but not to reduce lead levels or clear it from affected properties.

Ensuring lead’s absence in school water should absolutely fall under the purview of the EPA, said Bell. The agency has the authority “to require water systems to take certain actions, and it’s our position it can require water systems to take action in schools”. She and other experts hope that the EPA’s 1991 lead and copper rule, which is being updated and should be finalized later this year, might be another appropriate instrument to regulate school water.

Bell said the proposed improvements as they are currently written are “lackluster” and “just completely disappointing … leaving schools and childcare centers behind”. The only muscle the rule currently flexes is a provision mandating that states offer lead testing to 20% of their schools and childcare facilities every year. It must provide them with guidance around what EPA calls its “3Ts”: training, testing and taking action. Testing would be free, but it would also be voluntary. Many education sites already opt out for fear they will be on the hook for costly fixes.

In the last several years, federal help has softened some of the burden of paying for lead contamination cleanup. The Biden administration made $15bn available through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to replace lead service lines, and federal grants under the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation (Wiin) Act gave states $58m to replace lead pipes and hardware specifically in schools and daycare centers in 2022 and 2023. But that’s not nearly enough to tackle lead problems in every facility, according to experts.

The NRDC has advocated for the EPA’s lead and copper rule improvements to require lead testing for all schools and childcare centers twice a year, with mandatory lead reduction for facilities with levels over 1ppb. It has also pushed for what seems a less expensive alternative: the addition of filters on every tap, to make sure kids are not additionally exposed through food cooked in the school kitchen or fountains outside the cafeteria. Hecht, of the University of California, also said that potable water should be available throughout school buildings to better ensure safe hydration.

However, she pushed back on the NRDC’s push for “filter-first” legislation due to expense and maintenance needs; replacing filters can be costly and time-consuming, too. She would like more schools to follow the example of Chicago’s public schools, which rigorously test and flush taps to remove any lead that may have accumulated in pipes over class-free weekends and holidays.

But at this point, experts say they would welcome any federal mandate around lead tests and remediation because as things currently stand, said Bell, “the agencies we expect to protect children at school and at daycare simply put blinders on regarding this issue”.

Reporting for this piece was supported by the Nova Institute for Health

Yahoo News

Yahoo News