Leon Kossoff: Figurative and landscape painter who chronicled London life

What would a Jubilee line train look like if Nicolas Poussin had painted it? Certainly not like the one in Leon Kossoff’s Between Kilburn and Willesden Green, Winter Evening (1992). Poussin was the master of the icy surface, the frozen moment; Kossoff, who has died aged 92, made his name in thick impasto and expressionist gesture.

Yet the French classicist was one of his heroes, a painter whose works Kossoff transcribed for more than 70 years, sketching them tirelessly, day after day, in the National Gallery in London. “I go back to [Poussin] because I’ve a terrific sense that I can’t draw,” Kossoff said. “He worked as a draftsman in paint.”

That faith in draftsmanship made Kossoff a rarity in post-war English painting. In contrast to Francis Bacon, his most famous fellow member of the School of London, Kossoff believed in drawing. If Bacon was inspired by the Old Masters, it was via photographs of their work, mechanical reproduction imposing its own modernist gap. Kossoff came from a different bloodline. A student of David Bomberg, who had been taught by Walter Sickert – who was a pupil of Whistler who had studied with Courbet – Kossoff was, at heart, an Old Masterly painter. Yet his thick, tortured-looking paint, seen most memorably in the serial depictions of Christ Church, Spitalfields, which he began in 1987, looks resolutely anti-traditional.

Kossoff’s canvases were in a sense artefacts rather than simply as art. A picture such as Christ Church, Spitalfields, Morning (1990), now in the Tate, will have taken months, possibly years, to make. Contained in the work is not one way of seeing, but an accumulation of them: the dozens of mornings on which Kossoff will have stood in front of Hawksmoor’s church to build up his image, each with its particular quality of light, its own mood.

Kossoff’s parents, Jewish bakers, had fled the pogroms of the tsarist Ukraine for the East End of London in 1904. “My mother and father emigrated from Russia and the world I grew up in was fairly medieval,” Kossoff recalled. “There wasn’t much culture in that world.” Art came as a revelation to the couple’s nine-year-old son. Taken to the National Gallery on a trip from Hackney Downs School, he recalled, he immediately sat down and sketched Rembrandt’s Woman Bathing in a Stream.

Evacuated to King’s Lynn in 1939 to escape the German bombing of London, the young Kossoff was billetted with a couple with artistic leanings, a Mr and Mrs Bishop: when they encouraged their lodger to draw, he sketched newspaper pictures of St Paul’s engulfed in flames. Both the building and the act of recording it became symbols of survival, history recalled historically. Returning to London in 1942, Kossoff found that his family had been bombed out of his childhood home and had moved into a house in the shadow of Christ Church Spitalfields.

After three years’ military service with the 2nd Battalion Jewish Brigade of the Royal Fusiliers, Kossoff went to St Martin’s School of Art in 1949. There he met Frank Auerbach, later to be co-opted with him into the School of London. Auerbach, from a family of sophisticated German Jewish lawyers, took the older Kossoff along on painting expeditions, the pair visiting the bomb sites and ruins of post-war London and rebuilding them on canvas in thick, workaday paint. Auerbach also introduced his new friend to David Bomberg, by then sidelined as an artist and teaching at the Borough Polytechnic.

Bomberg and Kossoff had much in common. The ex-Vorticist had grown up in Whitechapel as one of 11 children of a Polish-Jewish leatherworker and at the time was supplementing his income from art by working, like Kossoff’s father, as a baker. More importantly, Bomberg believed in drawing as crucial to painting, a view not widely held in the early 1950s. His impact on Kossoff was electrifying. “What David did for me was more important than any technique he could have taught me,” he said. “He made me feel I could do it.”

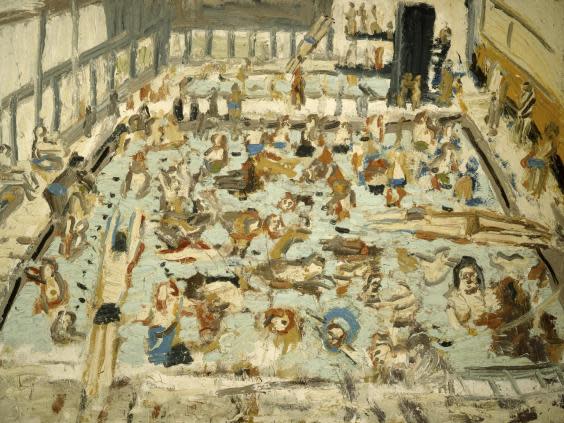

Rather than signing up to any group, Kossoff, remained a loner. His own genius lay in capturing the anonymity of the city which was to be home for his entire life. The subjects he found in London have the thrilling storylessness of faces in a crowd. There were the Tube trains that ran at the end of his garden in the dowdy suburb of Willesden Green, emerging from beneath Kossoff’s crust of impasto as though from underground. Years would be given over to painting red-brick school buildings or a single railway bridge; then, in the 1960s, to municipal swimming baths. There were repeat portraits of a sitter called Fidelma, of Kossoff’s assistant, Ann Dowker; of Ridley Road market, of Hackney and Dalston. All these Kossoff treated in the same even-handed way, seeing the tracks and whorls of his paint less as gestural or expressionistic than as simply graphic, rooted in the history of drawing.

In 2007, the National Gallery squared the circle by showing works Kossoff had drawn from the pictures in its own collection.

Like Auerbach and Bacon, he was never made a Royal Academician and, like them, he would probably not have wanted to be. (A CBE was turned down in the 1990s.) Art was, above all, a way of explaining himself to himself.

“From the earliest days when I scribbled from the Rembrandts in the [National Gallery], my attitude was always the same,” Kossoff said. “To try to understand why certain pictures have a transforming effect on my mind.”

He is survived by his wife Rosalind, known as Peggy, their son David, four grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Leon Kossoff, painter, born 10 December 1926; died 4 July 2019

Yahoo News

Yahoo News