Leonard Nimoy’s battle with Gene Roddenberry – and Shatner’s belly – to make The Search for Spock

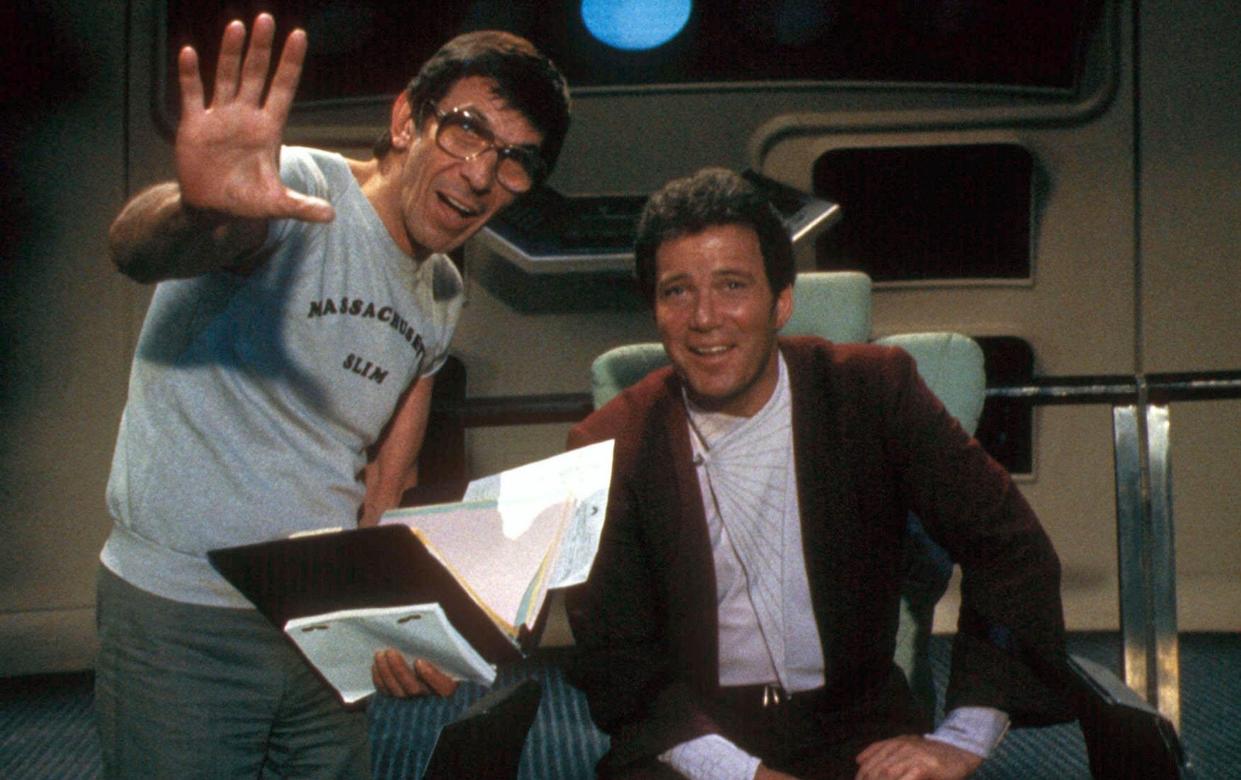

Captain Kirk didn’t think that Mr Spock could steer the ship. More specifically: William Shatner had doubts about Leonard Nimoy directing Star Trek III: The Search for Spock. He wasn’t sure if Nimoy, a first-time feature film director, was up to the job.

There were other reservations. The dynamic with Nimoy – his co-star on screen and subordinate on the bridge – had changed. “My friend had abruptly become my boss,” Shatner recalled.

Shatner also raised concerns about the script – a “tepid adventure” – and asked for a meeting with Nimoy and writer-producer Harve Bennett. He was prepared to walk away from the film.

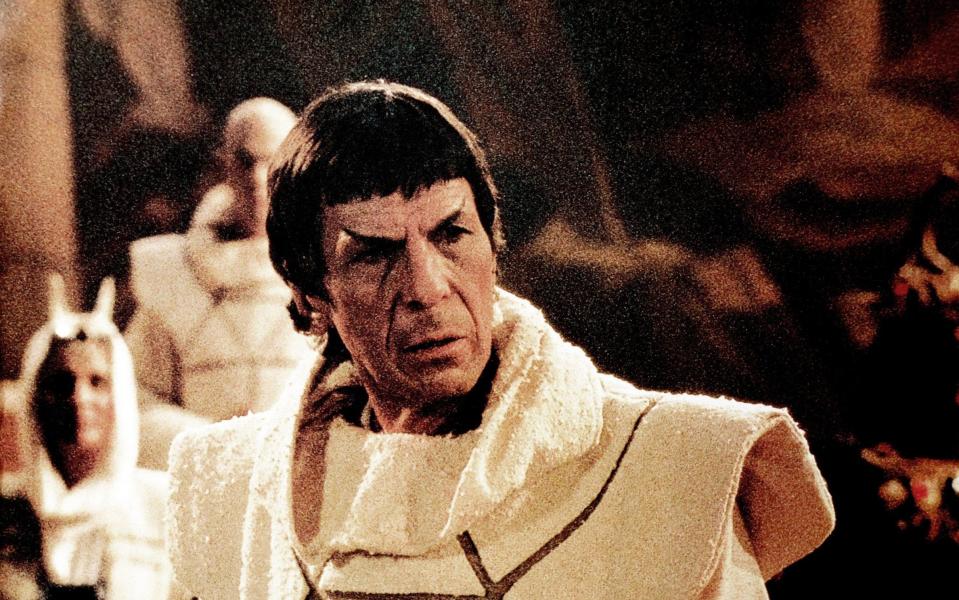

For Leonard Nimoy, directing was a condition of returning as Spock. The character was killed off – though with a few get-out clauses – in the previous, much celebrated sequel, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (“Khaaaaan!”). To Nimoy’s credit, Star Trek III: The Search for Spock never feels like the cheat that it ultimately is, reversing the galaxy-shaking sucker punch of Spock’s death so Star Trek could live long and prosper at the box office.

It’s sometimes tarnished by the oft-repeated adage that odd numbered Trek movies are a load of old Klingon excrement. But Star Trek III is the bridging chapter of Star Trek’s essential movie trilogy – comprising the second, third, and fourth films – linking Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, the critical favourite, with Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, the most successful film with the original crew.

“It’s the middle child [of the series],” says Larry Nemecek, host of The Trek Files podcast. “It’s the one with the famous older brother and amazing younger brother. It’s the one in the middle that did the heavy lifting and helped the story along.”

Star Trek III: The Search for Spock – now back in UK cinemas to mark its 40th anniversary – did more than resurrect Spock. It was a Trek-verse trendsetter and gave Kirk one of his great dramatic moments (“You Klingon b------!”). And in true Trek form, it provoked controversy among Trekkies by killing off another big name: the Starship Enterprise.

Contrary to a persistent story, Leonard Nimoy didn’t hate Spock – and he certainly didn’t campaign for Spock to die. He did, however, have a complicated relationship with the character. And Nimoy didn’t much enjoy the first Star Trek film – Star Trek: The Motion Picture – released in 1979. “By then I felt I’d taken off the Spock ears for the last time,” Nimoy wrote.

It was Harve Bennett who pitched the idea of Spock dying in Star Trek II. “Leonard, if you come back,” he said. “I’m going to give you the greatest death scene since Janet Leigh in Psycho.”

A grand death – Spock sacrificing himself to radiation to save the crew – was too tempting. But Bennett came from television – he always had an eye on the next episode. Bennett suggested that before going to his death, Spock should do a quick “mind meld” – a Vulcan psychic link – with Dr McCoy (DeForest Kelley) and tell him “remember” (for reasons yet to be explained). Following test screenings, Bennett also inserted a final shot: Spock’s coffin, which had been shot out into space, sat among the lush forests of the newly formed Genesis Planet – a world grown by life-creating technology.

Nimoy was profoundly moved by seeing Spock perish. Writing in his second memoir, Nimoy admitted feeling like “a co-conspirator in his death... The guilt was awful.”

Nimoy, however, was surprised by the added-in shot of Spock’s coffin. He knew a call from Paramount was imminent. Harve Bennett received a similar call. Just days after the release of The Wrath of Khan – then the biggest weekend gross of all time – Paramount boss Michael Eisner called Bennett and told him to start writing Star Trek III. “The fastest greenlight on any project I’ve ever had,” Bennett said. There were obvious threads to pick up. “The Search for Spock wrote itself,” says Nemecek.

In the film, Kirk has to retrieve Spock’s body and take it to the planet Vulcan along with his katra – a Vulcan’s living spirit – which was transferred to McCoy via the mind meld. At the same time, the Genesis Planet is developing and evolving at a dangerous rate and is declared a no-go zone – so Kirk hijacks the Enterprise to get there. Part of the fun is that Kirk, by this point an admiral, just can’t stop himself from adventuring. Spock, meanwhile, is reborn as a child on the Genesis Planet but, like the planet, is ageing rapidly. He reaches his painful Vulcan puberty in a matter of hours.

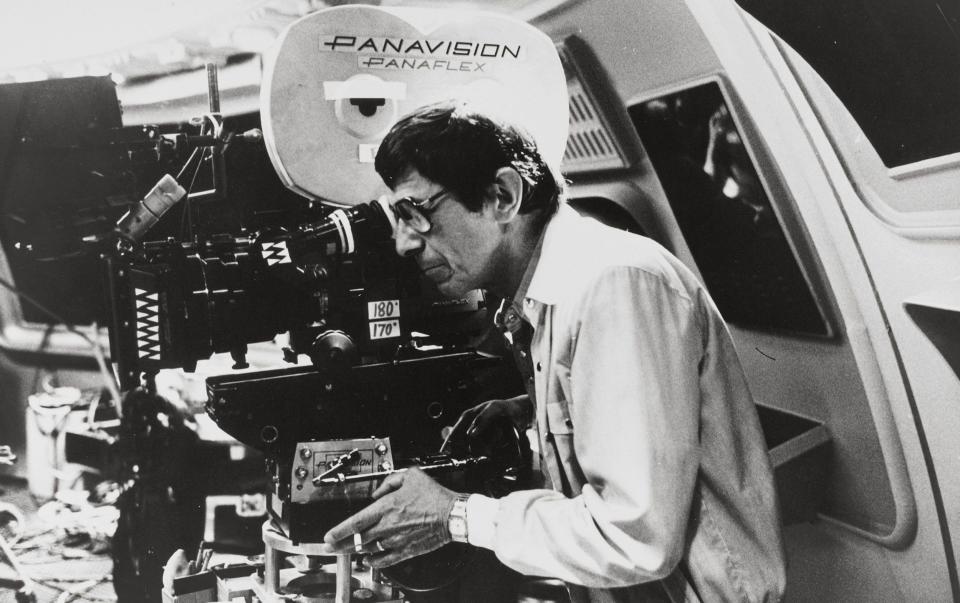

Nimoy was more enticed by the challenge of directing than he was the money. Both Nimoy and Shatner had designs on directing Star Trek since the original 1960s series, but both were denied. But when Nimoy told Paramount bosses he wanted to direct Star Trek III they were enthusiastic, but weeks passed without hearing anything. Nimoy eventually called Michael Eisner, who had decided that he couldn’t have a director who hates Star Trek. Eisner thought that Nimoy had Spock’s death written into his Wrath of Khan contract.

The common misconception – that Nimoy hated Spock – was partly born from Nimoy’s first memoir, I Am Not Spock (corrected by his second memoir, I Am Spock). Nimoy met with the studio boss in what Nimoy remembered as a “dramatic confrontation”.

Nimoy told him: “The way I see it, you have two problems. You want Leonard Nimoy to play Spock in Star Trek III, and you need a director for this movie. I can provide you with the solution to both of those problems, or neither. It’s that simple.”

Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry wasn’t particularly enthused by the idea. He told Paramount, “Well, you’ve hired a director that you can’t fire.”

Roddenberry had a tricky relationship with the Star Trek movies. As Nemecek explains, he had been effectively “demoted” to an executive consultant role after the stodgy first movie. Roddenberry was kept onboard largely to appease the diehards – to “keep the fans settled down,” says Nemecek. “He was probably the noisiest and most-paid-attention-to executive consultant ever.”

Roddenberry wrote memos and gave feedback on creative decisions. He admitted that he didn’t like the direction of the films and leaked details to weaponise fans’ voices against the producers. Star Trek fandom had campaigned and argued against creative decisions long before social media, dating back to the letter writing campaign to prevent the TV show’s cancellation in 1967. “The DNA of Star Trek fandom has been pushback,” says Nemecek.

Nimoy was wounded by Roddenberry’s initial reaction and was later surprised when he learned his Enterprise crewmates weren’t entirely thrilled about him directing. “People were just wondering what it would be like to suddenly have a director from among themselves,” says Nemecek.

There had also been some ego jostling with Shatner from the beginning of Star Trek. They barely talked for last few years of Nimoy’s life. (“We don’t have that kind of relationship anymore,” Nimoy said in one of his final interviews.)

Nemecek explains that when Star Trek launched in 1966, TV casts were still based around “the lead, the second banana, and everybody else”. This was before ensemble casts became a TV standard. He continues: “Spock’s popularity came out of the blue and it threw Shatner. I don’t want to say it was jealousy, but he did say, ‘Guys, I am the lead of the show, remember?’ At the same time Nimoy was like, ‘Look at my fan mail! Look at the attention I’m getting!’”

It led to what was dubbed a “favoured nations” agreement, in which Shatner and Nimoy got equal treatment. If one got a pay rise, so would the other, and so on. It also led to Shatner getting his own turn at directing a Trek movie – 1989’s Star Trek V: The Final Frontier.

On Star Trek III, however, Nimoy wanted every crewmember to have a moment – DeForest Kelley as McCoy, George Takei as Sulu, Nichelle Nichols as Uhura, Walter Koenig as Chekov, and James Doohan as Scotty. Nimoy took inspiration from his days on Mission: Impossible and gave each crewmember a specialist role in hijacking the Enterprise.

In one scene, Kirk and Sulu rescue McCoy, who – under the influence of Spock’s katra – is being sent to the “Federation funny farm” (sensitivities around mental health have obviously relaxed by the 23rd Century). George Takei was unhappy with one of the guards calling Sulu “tiny” – he complained that fans wouldn’t accept the slur against Sulu’s stature. But when Takei saw the finished film, he had to admit he was wrong. The crowd roared with approval when Sulu flipped the guard over and told him, “Don’t call me tiny.”

Also joining the cast was Christoper Lloyd, who brought some Doc Brown energy to the Klingon baddie, Kruge. Lloyd was then best known for his role in the sitcom, Taxi, and studio bosses were concerned about casting a comedy actor. The Klingons do feel played for laughs at times. See the moment in which one Klingon accidentally destroys a Starship with a mislasering. “A lucky shot, sir,” he quips. Kruge, who has a pet monster-lizard-dog thing at his side, vaporises the Klingon joker.

But as Nemecek says, it’s a crucial portrayal of Klingons as “swaggering viking bikers”. It’s only the second time the alien warriors appeared with their ridged foreheads, which were added for the first movie. “Star Trek III set the pattern for Klingons, through all the other movies and TV series,” says Nemecek. “The Search for Spock set up so much that became standard Star Trek – it has these landmark touchstones.”

Indeed, it’s the first time the Klingons fly a Bird-of-Prey ship (a hangover from the fact the film’s baddies were meant to be pointy-eared Romulans – the original Bird-of-Prey pilots). It’s also the first appearance of the Federation Spacedock and the USS Excelsior. The Excelsior is the latest Starship upgrade, while the Enterprise is about to be decommissioned. Scotty sabotages the Excelsior’s souped-up transwarp drive – the 23rd Century equivalent of tampering with the engine. But he Excelsior still flew around the periphery of the film’s biggest controversy: Kirk blowing up the Enterprise to kill a few Klingons.

Before The Wrath of Khan, word leaked that Spock would die – the leak came via Gene Roddenberry’s secretary – which led to outrage and even death threats. This time around, Harve Bennett insisted on strict security measures: double-locked offices, script pages delivered on a need-to-know basis, and codenames for the production. The scripts were also chemically treated so copies could be traced back to the original owner.

But the destruction of the Enterprise did leak. The reaction wasn’t quite at the level of “if Spock dies, you die”, but fans were upset.

The controversy was compounded by visual effects supervisor Ken Ralston, who declared that he wanted to “take a mallet” to the Enterprise model, which was cumbersome and hard to shoot. He settled for blowing up a smaller version. “I’ve always said I hated that ship,” Ralston told Cinefex. “I tell you it was wonderful: Boom! Goodbye!”

Shatner recalled that Paramount lapped up the free PR of the Enterprise controversy – the destruction of the Enterprise even appeared in one of the TV trailers. “Paramount’s powers-that-were simply sat back, smiled and rode the wave, milking the controversy for every sound bite they could wring out,” Shatner wrote.

Shatner was also subject to some amusing behind-the-scenes stories. Costume designer Robert Fletcher told Cinefantastique that Shatner needed 12 shirts: “He diets before a movie and shows up looking terrific. But he would slip as it went along.”

Robert H Justman, a co-producer of the original TV series, reported a similar problem back in the ‘60s – as the season rolled on “the top of [Shatner’s] pants and the bottom of his tunic moved inexorably away from each other as they got smaller and he got larger”. Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry sent memos about Shatner’s weight gain and Shatner, during the third season, went on a crash diet after seeing himself in the dailies.

But Star Trek III gave Shatner what might be – according to Shatner himself – “Kirk’s finest celluloid moment ever”. These Klingons are occasionally goofy, but they’re ruthless too, as proved when one of Kruge’s warriors stabs Kirk’s son to death. Nimoy told Shatner to play the reaction however he wanted. Kirk stumbles, withdrawing from the immediate trauma, and drops down. “You Klingon b------, you’ve killed my son,” he repeats.

“Somehow, that never got to meme-hood in the way that ‘Khaaaaan’ did,” says Nemecek.

Kirk gets revenge in another great moment, fighting Kruge on a not-entirely-convincing volcanic clifftop. Shatner recalled pulling out his classic moves. “The giant windup into a left-handed haymaker, the roundhouse kick, the two quick jabs to the stomach followed by a right to the jaw.”

As ever, the intonation of Shatner’s delivery is imitable – the random breaks and coupling of words. “I. Have had. Enough of. You!” he says, booting Kruge into the lava.

The climax of Star Trek III is slightly less action-packed. After getting his katra back on Vulcan, Spock – now aged back into Leonard Nimoy – recognises Kirk. “Jim,” he says, “your name is Jim.” Perhaps more important is the film’s parting message: “... and the adventure continues...”

Released on June 1 1984, Star Trek III made $87 million – not as much as Star Trek II but still a success. Even before the film opened, Paramount asked Nimoy to make another. The next film was an even bigger triumph – Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, a comedic time-travel romp about saving humpback whales. Shatner’s effort, Star Trek V: The Final Frontier – Kirk vs God – was less successful.

“Five is the one that everybody loves to kick around,” says Nemecek. He adds: “All the movies, good or bad, have some notoriety. Star Trek III is the one that kept its head down and did its job.”

Even Shatner – despite initial reservations – conceded that Nimoy had excelled in his mission as director on Star Trek III. “Leonard was absolutely great,” wrote Shatner. “Kicked that picture’s a--.” Not the best Star Trek movie, perhaps, but in keeping the film series boldly going, a logical one.

Star Trek III: The Search for Spock is in cinemas now

Yahoo News

Yahoo News