The Life of Riley: Inside the artistic world of a Greater Manchester icon

It is a story of two lives. That of the artist and his city.

A retrospective exhibition of Harold Riley's work does not shy away from the sadness and brutal nature of living as well as its joy. The vivid red shirts almost beat with pride as George Best and Bobby Charlton celebrate a goal at Old Trafford. But paintings of Riley's father near death and a dishevelled meths drinker slumped in a street are powerful and haunting.

Entwined around his devotion to Salford is his Catholic faith, a passion for recording his city's streets and people, humour, and the fact he was 'blessed' with a talent. There are 70 paintings, drawings, photographs, and mixed medium works.

Some of those he painted were famous on a world stage. Then there was the well-read recluse, Alice Fairweather, who died on a mattress in his garden in 1975. "I looked after her as nobody else did," he recalled.

A pastel of his 'much loved' first wife, Hannelore Reuter, captures her elegance. They married in 1962 and they had a daughter, Kate. Hannelore died in 1973 and in 1975 Harold married Ashraf Danesh, with whom he had a daughter, Sara.

An oil painting of his father is called 'The Patient' and is stark in its brutal honesty. Harold's comment for the work is: "This my father not long before he died. He went into hospital, and I brought him home like that. This was in ’59 and he smoked 80 cigarettes a day."

The exhibition which opened quietly, without fanfare on April 19th - the first anniversary of Harold's death, aged 88 - will run for a year. It is being staged at Salford Museum and Art Gallery, to whom he sold his first painting.

Another pastel of Ashraf wearing a blue dress and delicate jewellery perfectly reflects what Riley describes as her 'very regal look'. With typical grace his comment on a caption of the work reads: "I always think I am very, very happily married".

Harold was 11 years old when he first met LS Lowry, who would become a life-long friend and mentor. He was awarded first prize by the artist at a Salford Grammar School art exhibition in 1945. They were friends for 30 years.

Lowry engineered the first sale of a picture by Harold. He invited him to Salford Museum and Art Gallery, and had a word with Albert Frape, curator at the time. Lowry suggested a price of 30 shillings which Frape paid and Mr Riley used the cash to buy a new plaid shirt.

The painting he sold was the result of his 'first project' spending a summer next to railway tracks on the Liverpool to Manchester line and a second line to the Manchester Ship Canal, sketching a bridge.

Viewing the exhibition alone on a Monday - when the gallery is closed to the public- was a privilege. It reflects not just the history of a city through one man's eyes, but opens a door to Riley's authentic dedication to his craft - 'I draw from the moment I get up till I go to sleep' - and his life's work painting Salford and its people.

There are works from 1959 for which he won accolades while a student at the Slade School of Fine Art - after Sir Matt Busby told him, aged 17, that art not football, was his destiny as he played for United's academy.

After completing a course at Slade he won a travel scholarship to Italy, followed by a British Council Scholarship to study in Spain and went on to study in Florence and Madrid University before returning to Salford, where he lived until he died.

He returned to Salford in 1960 and recalled: "I felt more fulfilled than I had ever done before when I returned to Manchester...Salford and Manchester as industrial towns, I loved the drama."

He believed his main work was to document the city and his life-cycle in paintings, drawings and photographs. His deep affection for his home town cemented the friendship with L.S. Lowry; together they worked on a project to record the area and its people.

The location for the exhibition is fitting - more so than the new Lowry arts centre at the former Salford docks.

Ashraf said: "Salford Museum to Harold was not a shelter for fugitives but a mehrab for the spiritual. Harold loved the City of Salford, the city of his birth, his childhood, and where he grew up to be an artist as a young man.

"His city cemented in him admirable qualities of love, loyalty and an unstoppable sense of duty and honest service.

"His genuine determination was to simply portray what he saw in Salford, from its streets, buildings, shops, hospitals, families, children and its dogs.

"Honest cities and honest families produce honest citizens – Harold was one of its honest citizens. We can look at this city and its museum and see for ourselves a small section of Harold’s art exhibited and understand he was one of Salford’s talented, loving and honourable sons."

The vast breadth of Harold's work is faithfully shown. A huge portrait of the late Duke of Edinburgh, who he painted when he was Chancellor of the University of Salford, is included.

Prince Philip later told Riley on seeing the work: "You've got a look on my face I've been trying to get rid of for 50 years".

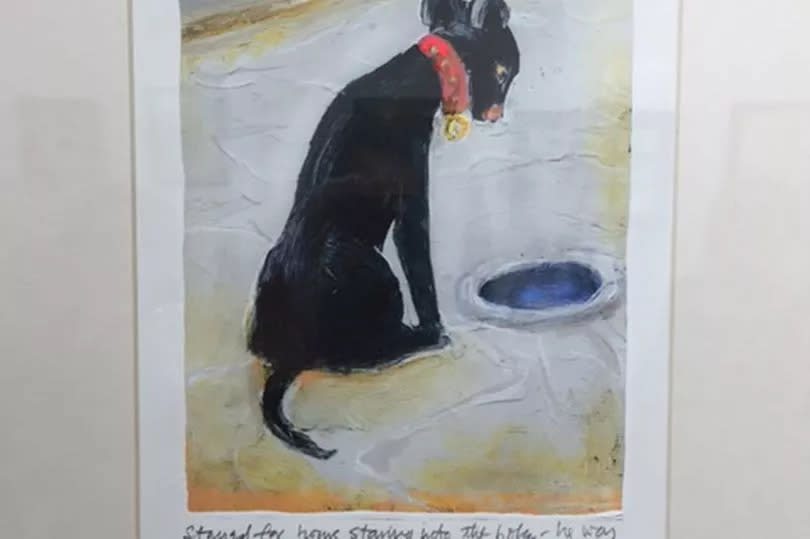

There are portraits of athlete Seb Coe, Nelson Mandela, and L S Lowry's with his hands clasped around his glasses about to walk across Swinton Moss - and of his children and his daughter's dog, Bonzo.

Painting Mandela was a highlight of Harold's career. He recalled: "‘He and I got together for a series of studies and eventually I painted his portrait.

"It sold in New York City in a gallery above 5th Avenue for well over £1 million. All the money went to children in the townships.

"My experience of spending time with him was one of the greatest experiences of my life. I’m the only one he ever sat for. He had a magical charisma; you can’t paint charisma, as it’s a magic energy. He loved art. A lot of people didn’t realise he painted."

Riley's passion for painting everyday Salford - whether it was Neil's Friery chippy on Langworthy Road or Chimney Pot Park, was equal to when he was producing portraits of sporting greats and world leaders.

A portrait of John F Kennedy and a backstreet in Brindle Heath demanded the same time, skill, and flair. His final works were of staff caring for him in Salford Royal Hospital - an appropriate way to end the cycle of life brilliantly conveyed in the exhibition.

During the 1960s, 70s, and 80s Harold documented the changing streets of Salford - with both his artwork and photography - and was often seen with easel, sat next to a soon to be bulldozed pub or row of terraces.

His red E-type Jaguar was a striking juxtaposition to cobbled half demolished streets and elderly women in shawls and clogs. The exhibition includes a collection of his cameras.

Before she found fame aged 18, by writing A Taste of Honey, Shelagh Delaney was an old flame of Harold's. He went to school with actor Albert Finney and author Walter Greenwood, and charcoal drawings of both are in the exhibition.

'Every Line is Me' showcases his work across two sites, created between the 1950s, up until his death. The exhibition is part of the wider Harold Riley celebrations taking place at Salford Museum and Art Gallery, Ordsall Hall and online during 2024 and 2025.

Other elements included in the exhibition are quotes and stories from Harold to give an insight into the huge legacy of work he has left.

He regarded walking the remnants of Salford's docklands - and later the Quays next to the Manchester Ship Canal- as a place 'to think'.

His final home was an apartment near the Lowry arts centre, overlooking the canal, United's Old Trafford ground, and the streets of Seedley and Langworthy where he was raised.

Reminiscing, he said: "It's not exactly the Venice of the north, but it's home to me."

Harold set up The Riley Educational Foundation to support schools and art in the north west. His dedication to Salford was recognised in 2017 when he was awarded the Freedom of the City and he exercised his ancient rite to herd sheep through the city - mustering four pedigree Derbyshire Texels from a farm to meander slowly down the A6.

The wider celebrations of Harold’s life include a collaboration between Salford Museum and Art Gallery and Pinc College which is an exhibition of Harold-inspired portraits created by students. The college is a specialist facility for neurodiverse 16-25s and is based at Salford Museum and Art Gallery, and other museums in the region, offering creative courses for the community. The exhibition will be shown in the Park Gallery from now until June 30th.

Harold produced books of sketches of Salford's street dogs and his own pets inspired his work. In July at Ordsall Hall they will feature in a separate exhibition.

Salford Museum and Gallery exhibitions manager, Amy Brunn, said: ‘We are honoured to showcase the wonderful work of Harold Riley, celebrating his life and talents.

"We were incredibly lucky to work with Harold for many years and we’re grateful to his family for all of their support for these exhibitions. We hope to welcome many visitors from around the world to appreciate the legacy of Salford’s talented artist."

Last year when news broke that Harold had died, Sir Alex Ferguson told the Manchester Evening News: "News of Harold Riley’s passing brings instant sorrow to the people of Manchester and Salford.

"Having first met him in 1986 when I arrived in Manchester, his reputation was well established as a working class man who had risen to great heights as a unique artist who never lost his roots.

"He had a style of his own and his generosity in supporting countless charities still reverberates round the streets of his home town.

"When Harold spoke of donations of his work to these worthy causes he spoke as if it was the first painting he had ever produced, such was the enthusiasm of his words. It was a privilege in my life and for many, many others to call him a friend."

Harold’s work at the main Every Line is Me exhibition will be on display until 27 April 2025 in the Langworthy Gallery, Salford Museum and Art Gallery.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News