We’re living in a cyberpunk dystopia – according to the greatest sci-fi novel of all time

Fortune-tellers employ a variety of psychological techniques. “Cold readers” seize on specific details volunteered by the subject, or pick up on involuntary tells, while “shotgunning” conveniently vague yet suggestive prompts (“I see a father figure who is no longer around”) designed to extract more information. The idea is to exploit confirmation bias – our well-known tendency to pay more attention to things that support pre-existing beliefs. At their best, these fortune-tellers are acute readers of body language and subliminal clues. For that, they are deemed innately suspect.

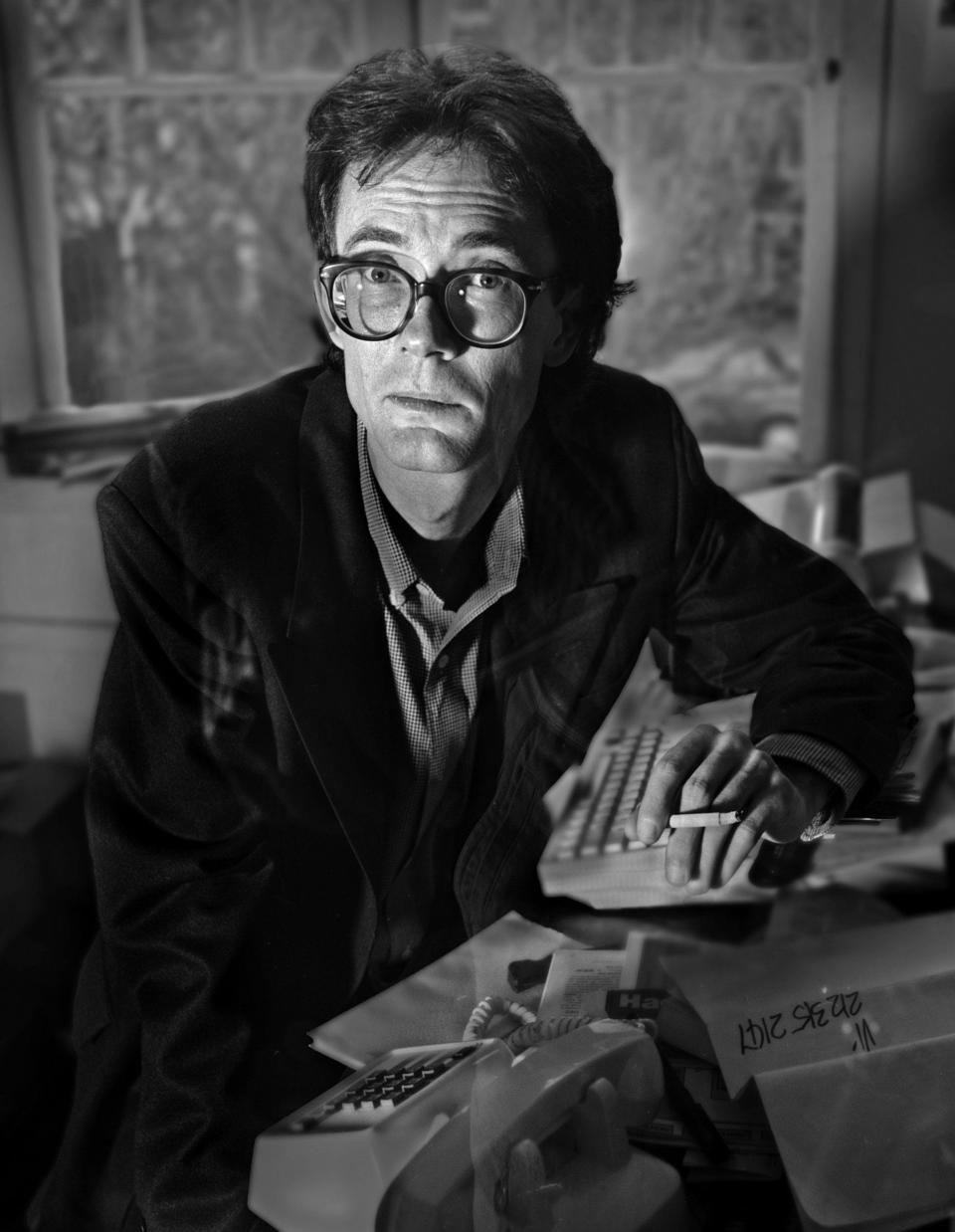

By contrast, authors are seen as truth-tellers, and sometimes the conscience of society. Even writers of fiction are assumed to tell lies to reveal deeper truths. Yet they use techniques similar to the much-derided clairvoyant, especially when writing about the future. At 76, William Gibson is heralded, with ample evidence, as being one of the most prophetic living writers.

So profound is his influence that it’s often claimed we are living in a world of his imagining. He coined the term cyberspace, popularised the idea of virtual reality, and gave intellectual weight to the genre of cyberpunk. Despite a remarkable bibliography, his reputation rests on the astonishing Neuromancer, which has sold more than six-million copies and scooped the Nebula, Philip K Dick and Hugo awards – the only novel to have won all three. Published 40 years ago next month, it is currently being adapted into a series for Apple TV+, starring Masters of the Air’s Callum Turner.

As in Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange and The Man in the High Castle by Philip K Dick, Gibson’s novel trusts the readers enough to throw them deep into the cities of the future. Even nature seems corrupted by the hex of technology, as Neuromancer’s famous opening line attests, “The sky above the port was the colour of television, tuned to a dead channel.”

We follow the antihero Case, a “console cowboy” hacker through realms where complex computer systems hide the fact that life and death are cheap. Hacking, drugs, prostitution, black markets and murder abound. Everything is for sale, above all data. Having robbed a nefarious employer, Case finds himself wounded and, worse, locked out of the hunting ground of cyberspace – the “matrix” – and must undertake clandestine missions to survive.

Like eyes adapting to a darkened room, it takes a while to orientate to Neuromancer but also to adjust to the speed. The temptation is to be carried along by the surge and bombardment of Gibson’s prose. Yet, for a book that is thrillingly filled with questions, how prophetic has Neuromancer actually been?

The most obvious and convincing responses are the internet and cyberspace, which now effectively dominate every part of our lives, something Gibson realised in the exact year when dystopias were supposed to be of the austere, ration-bound and bombed-out Orwellian kind. His accuracy at times is remarkable and yet the deviations are just as fascinating. Sometimes, reality hasn’t quite caught up yet. For instance, he places his megalopolis, “the Sprawl”, not in Los Angeles but in the “Boston-Atlanta Metropolitan Axis”.

What did Gibson get right? Increasingly in the West, cities are cosmopolitan, to a hegemonic degree. In Neuromancer, every city is a melting pot. There is an elite of “professional expatriates”, who are effectively supra-national; money and connections being the greatest passports. Gibson’s “drifting shoals” of rubbish in Tokyo Bay call to mind the North Atlantic and Great Pacific “garbage patches”. Neuromancer’s smuggler Julius Deane is “one hundred and thirty-five years old, his metabolism assiduously warped by a weekly fortune in serums and hormones”, which today calls to mind tech bros such as Bryan Johnson, who follow laborious regimes to reduce or reverse biological ageing.

Gibson’s portents do not have to be profound. Anyone who has received a call from their bank to ask if they are buying Louis Vuitton handbags a thousand miles away knows that card cloning is everywhere. There’s the suggestion of meat being grown in a vat, which chimes with lab-grown meat now being a plausible business model. The mention of a “holographic cabaret” might speak to fans of the CGI blockbuster show Abba Voyage.

We have, in various stages of use and development: adaptive camouflage, crowd-control sticky foam, maglev trains, genetically modified viruses, shapeshifting synthetic street drugs, nanotechnology, cryogenics, lab-grown body parts, and ghostbots mimicking departed loved ones. Even if our asset-stripped present seems light years from Neuromancer’s gang-leader Lupus Yonderboy, who wears “a polycarbon suit with a recording feature that allowed him to replay backgrounds at will”, the picture increasingly aligns. Full-body medical scans are available for those who can afford them. Even the name of the Swiss euthanasia organisation Dignitas chimes with Gibson’s biting line, “Suicides here are conducted with a degree of decorum.”

Gibson’s view that cyberspace would come to dominate our lives is true, even if the idea of surreptitiously buying “three megabytes of hot RAM” sounds laughable now. “Stop hustling and you sank without trace” rings true in a grifting age where opting out of being terminally online risks financial and social ruin. Virtual and augmented reality are largely entertainment novelties but are being used more and more to train surgeons, pilots and even chefs. The last barriers we have to losing ourselves completely in cyberspace are the physical interfaces required. With Wi-Fi and brain-chip implants such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink, the act of “jacking in” (propelling your consciousness into cyberspace via electrodes) might date Neuromancer more than anything else.

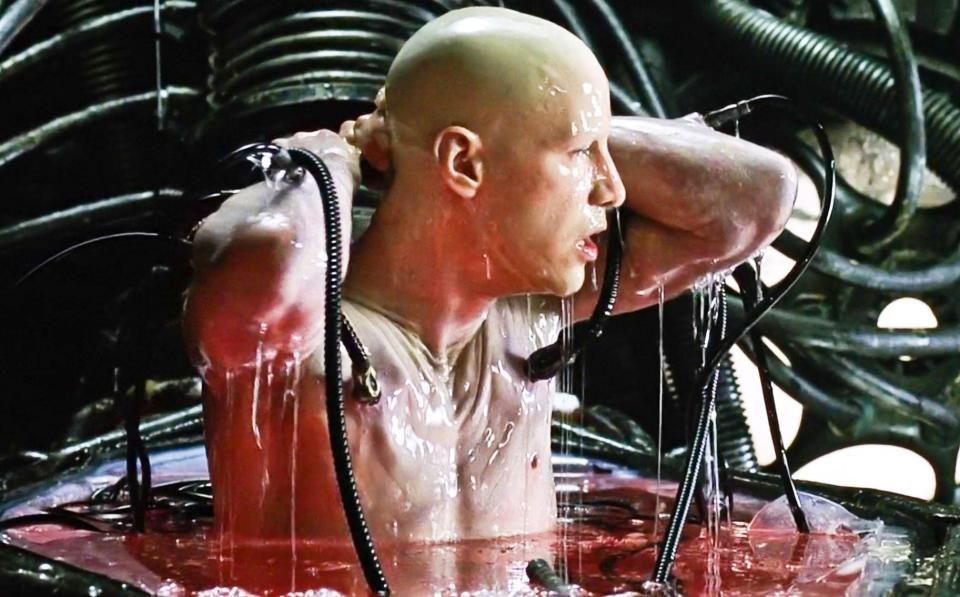

The most dazzling set-pieces in the book are the scenes where Gibson visualises cyberspace as “a simple cube of white light, that very simplicity suggesting extreme complexity… Its blank face, towering above him now, began to seethe with faint internal shadows, as though a thousand dancers whirled behind a vast sheet of frosted glass.” This “data made flesh” is compelling to read and has had a colossal influence on films (The Matrix for one), comic books and video games. Yet this necessary authorial trick belies the fact that so much of cyberspace, including much of its detrimental impact on us, is invisible.

The corporate-dominated future of Neuromancer was well-founded. “Power, in Case’s world, meant corporate power. The zaibatsus, the multinationals that shaped the course of human history, had transcended old barriers. Viewed as organisms, they had attained a kind of immortality. You couldn’t kill a zaibatsu by assassinating a dozen key executives; there were others waiting to step up the ladder, assume the vacated position, access the vast banks of corporate memory…” The financial crisis of 2007-08 was a fine example of how a system can escape human comprehension and accountability.

Gibson’s use of drones for purposes up to and including assassination resounds, morbidly, with our times. The prevailing tone of cynicism is recognisable, too. Presidents can be lauded as peacemakers while championing drone campaigns that annihilate wedding parties and leave children terrified of the sky. While drone warfare goes back as far as the First World War, Gibson’s intelligence lies not just in pushing existing threads, but in noting older impulses: the desire, for instance, of those in authority to keep their hands clean. He is as much an acutely psychological writer as a technological one.

At times, reality outpaces the script. When Neuromancer was published, Japan really did feel like the future – its economically stagnant Lost Decades and population decline not prophesied. The future went elsewhere. In the West, financial precarity makes Gibson’s lament seem practically aspirational: “Working all your life for one zaibatsu. Company housing, company hymn, company funeral.” Similarly, his nightmare of “wak[ing] alone in the dark, curled in his capsule in some coffin hotel” is no doubt endured by some inhabitants of capsule hotels, though these are more often sites of low-budget convenience. A more common misery, from the cage homes of Hong Kong to the micro-flats of London, are cramped “living” cubicles.

We’ve seen prominent cases of the wilfully grotesque body modifications Gibson envisaged (transdermal horns, antenna implants, etc) and pushbacks against them (the banning of cosmetic tongue splitting in the UK). Yet these are still largely peripheral compared with the big business of altering the flesh, via facelifts, buccal fat removal and rhinoplasty, to fit with orthodoxies of beauty.

And while Gibson describes e-waste as “a crystalline essence of discarded technology, flowering secretly in the Sprawl’s waste places”, it’s more likely now to have been exported and dumped in places such as Ghana. In some ways, Gibson was an unintentional utopian. In Neuromancer, Turing cops exist to prevent AI going autonomous (“Every AI ever built has an electromagnetic shotgun wired to its forehead”). In our world, given geopolitical divisions and profiteering, there’s little chance of such universal safety measures, and an AI “arms race” looks ever more likely. From the Cybertruck to the metaverse, Silicon Valley’s svengalis have long sought inspiration in dystopian sci-fi – so why have they never heeded its warnings? The truth is that in Neuromancer, as in real life, chaos is risky, but promises good returns. And the costs of upheaval are always borne by others.

It’s been said of Gibson that he’s the Raymond Chandler of science fiction. It is true that the book is an exemplary form of noir – conspiracies within conspiracies, a world of shadows and betrayals, where identities warp and even the dead cannot be trusted. Yet the more obvious pulp qualities haven’t aged so well, with the deadpan dialogue feeling kitsch at times, like a bad video-game cutscene.

Instead, Gibson’s achievement lies in his invention of evocative phrases (neon forests, nerve boys, Metro Holografix, razorgirls, dermatrodes, cybernetic spiders) that feel true to the future, before or even beyond rational understanding. (Gibson was enthralled and inspired by the enigmatic line in John Carpenter’s 1981 action adventure Escape from New York: “You flew the Gullfire over Leningrad” – so much is said in the unsaid.) Neuromancer, then, possesses the skill of an artful fortune-teller: that mix of the tantalisingly vague and the characterfully specific. Gibson utilises the iceberg effect to an intoxicating degree (the city of Bonn is an irradiated ruin, horses have mostly vanished “after the pandemic”). Even as the story descends into a thicket of subplots, so much is left to the reader’s imagination that, like the future, it feels infinite.

And if the danger in such a scenario is simply floating off into a kaleidoscopic void, Gibson is a classic noir writer in the sense that he knows certain timeless truths about human nature. For all our technological advances, moral progress might still be a comforting fairy tale we tell ourselves. When Case asks an all-powerful AI “You God?”, he might as well be asking for all of us, humanity itself, since time immemorial. The old lessons – Pandora’s box, King Midas, Narcissus, Prometheus – are just as true now as then. Stepping into the age of AI, it’s clear we are living in the last days of the world we know. Yet the wonders and terrors of the future, Gibson reminds us, will be all too familiar.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News