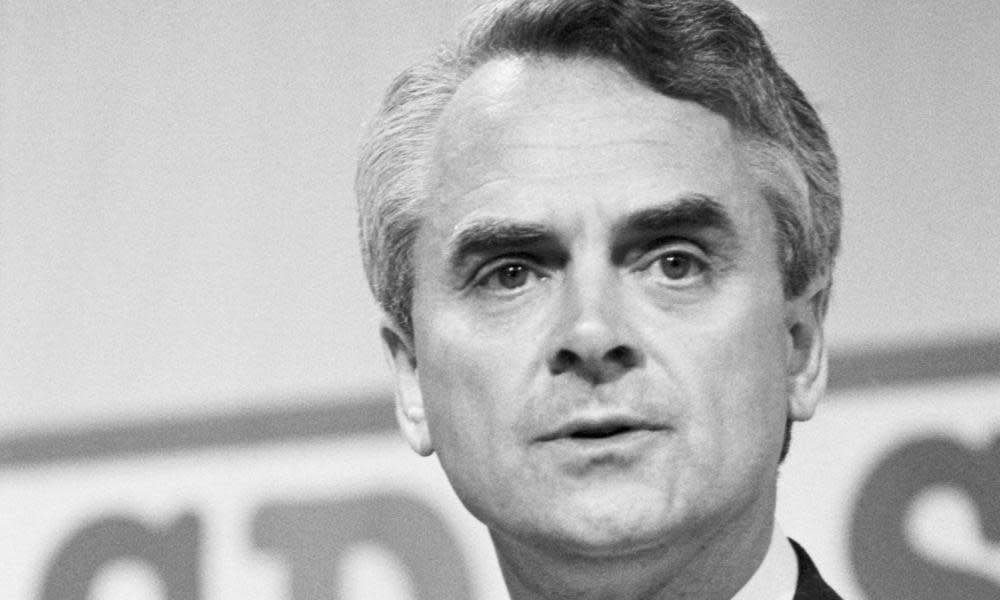

Lord Maclennan of Rogart obituary

As the third and last leader of the short-lived Social Democratic party, Robert Maclennan presided over its demise in 1987. An accidental leader, he lacked drive and colour when placed beside his predecessors at the head of the party, Roy Jenkins and David Owen.

In 1981 he was one of 28 Labour MPs who followed Jenkins, Owen, Shirley Williams and Bill Rodgers in splitting from Labour and forming the SDP. Although not as newsworthy as “the Gang of Four”, Maclennan designed the structure of the new party, which, supposedly learning the lessons of Labour’s system, excluded the membership from making party policy. Following general elections in 1983 and 1987, when the SDP failed to gain more than a handful of MPs in either contest, a ballot of its members in 1987 agreed that the party should merge with the Liberals.

Initially Maclennan was opposed to a merger, as was Owen, who resigned as leader in protest at the prospect. Other key SDP figures, including Rodgers, Jenkins and Williams, favoured a link up with the Liberals, but as they were no longer MPs there was no experienced person in the House of Commons to head the party in merger talks. They were therefore surprised and delighted when Maclennan made a U-turn and declared that he would now back the merger.

As the new leader of the SDP he agreed the merger details with the Liberal party leader David Steel and also prepared, with the help of some young aides, what was widely regarded as a disastrous founding policy statement for the Lib Dems – a document so widely disparaged on all sides that it led, in part, to Steel’s resignation. With Paddy Ashdown voted in as the new Lib Dem leader, Maclennan became a frontbench spokesman for the new party and, eventually, their president from 1994-98.

Maclennan was born in Glasgow into a medical family. His father, Sir Hector Maclennan, a gynaecologist, was president of the Royal College of Obstetricians, and his mother, Isabel (nee Adam), was a doctor. Educated at the Glasgow Academy, Maclennan then studied law at Balliol College, Oxford, and went on to Trinity College, Cambridge, and Columbia University in New York.

Called to the bar at Gray’s Inn in 1962, he practised in London as an international lawyer. As a Labour party candidate in 1966 he won the remote Caithness and Sutherland seat from the Liberals with a majority of 64 votes. He held on to it over the next 35 years under three different party labels, Labour, SDP and Lib Dem, often canvassing in his tweed suit with a rolled-up umbrella and steadily increasing his majority by attracting a substantial personal vote. He tried to make his constituency a centre for the arts in Scotland and spoke up for nuclear power (Dounreay, the local nuclear plant, was the largest employer).

As a Labour MP he was a “Jenkinsite”, a supporter of Jenkins; such MPs, often Oxbridge educated and recently elected, wanted to keep alive the flame of the late Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell.

Many distrusted Gaitskell’s successor, Harold Wilson, and Maclennan backed one of the first attempts to unseat Wilson in 1968. Along with like-minded MPs such as Rodgers, Williams, David Marquand, John Roper and Roy Hattersley, he also defied the party line in the early 1970s by supporting British accession to the EEC. He was a passionate supporter of the European Union until the end.

Maclennan’s one experience in government was as a junior minister in the Department of Prices and Consumer Protection, between 1974 and 1979. Given the government’s battle against high inflation, the department was often in the news. He worked well with his two secretaries of state, Williams and then Hattersley, but less so with trade union leaders; he found them abrasive and demanding.

Maclennan felt that he deserved promotion, but it never came, and colleagues believed that he failed to make the most of the opportunities to advance himself. More impressive in private than in public, and blessed with intellectual confidence, he was diffident in manner and often hesitant on the platform.

After his defection to the SDP and once the creation of the Liberal Democrats had gone through, Maclennan worked with Labour’s Robin Cook on a proposed programme of constitutional change for a future Labour government, perhaps in coalition with the Lib Dems. Labour’s landslide election victory in 1997 stymied hopes of a coalition, but Maclennan’s work helped to pave the way for an ambitious programme of reform carried out by Tony Blair’s government, which included devolution for Scotland and Wales, changes in the House of Lords and a freedom of information bill.

In 2001, after deciding to relinquish his seat, he took a life peerage as Lord Maclennan of Rogart (his father had owned a hotel in Rogart, which was in his son’s constituency) and was Liberal Democrat spokesman on Europe, Scotland and Cabinet Office matters.

Despite also serving as president of the Liberal Democrats in the late 90s, in private he thought that too often the party’s members went in for moralising and virtue signalling. Uneasy about the Cameron-Clegg coalition, he retained many of his Labour attachments but decided he was “too old to cross the floor again”.

Friends and constituents saw his thoughtfulness and kindness in ways that were not always appreciated in the cut and thrust of Westminster or in the intrigues of internal party politics.

A keen collector of art, he once wrote a libretto for an opera, and he also played the violin.

In 1968 he married Helen Noyes (nee Cutter), an American teacher. She survives him, as do his children, Adam and Ruth, and a stepson, Nicholas.

• Robert Adam Ross Maclennan, Lord Maclennan of Rogart, politician, born 26 June 1936; died 18 January 2020

Yahoo News

Yahoo News