‘Love hormone’ oxytocin could help heal damaged hearts, study finds

The hormone oxytocin, commonly dubbed the “love hormone”, has been found to have heart-healing properties, researchers have suggested.

Oxytocin is produced by the body during activities like breastfeeding and labour, sexual intercourse, and exercise. It is known for promoting and strengthening social bonds, and is also sometimes called the “feel-good hormone”.

The study, conducted by experts at Michigan State University, found that the hormone may have another function related to regenerating heart cells to promote healing.

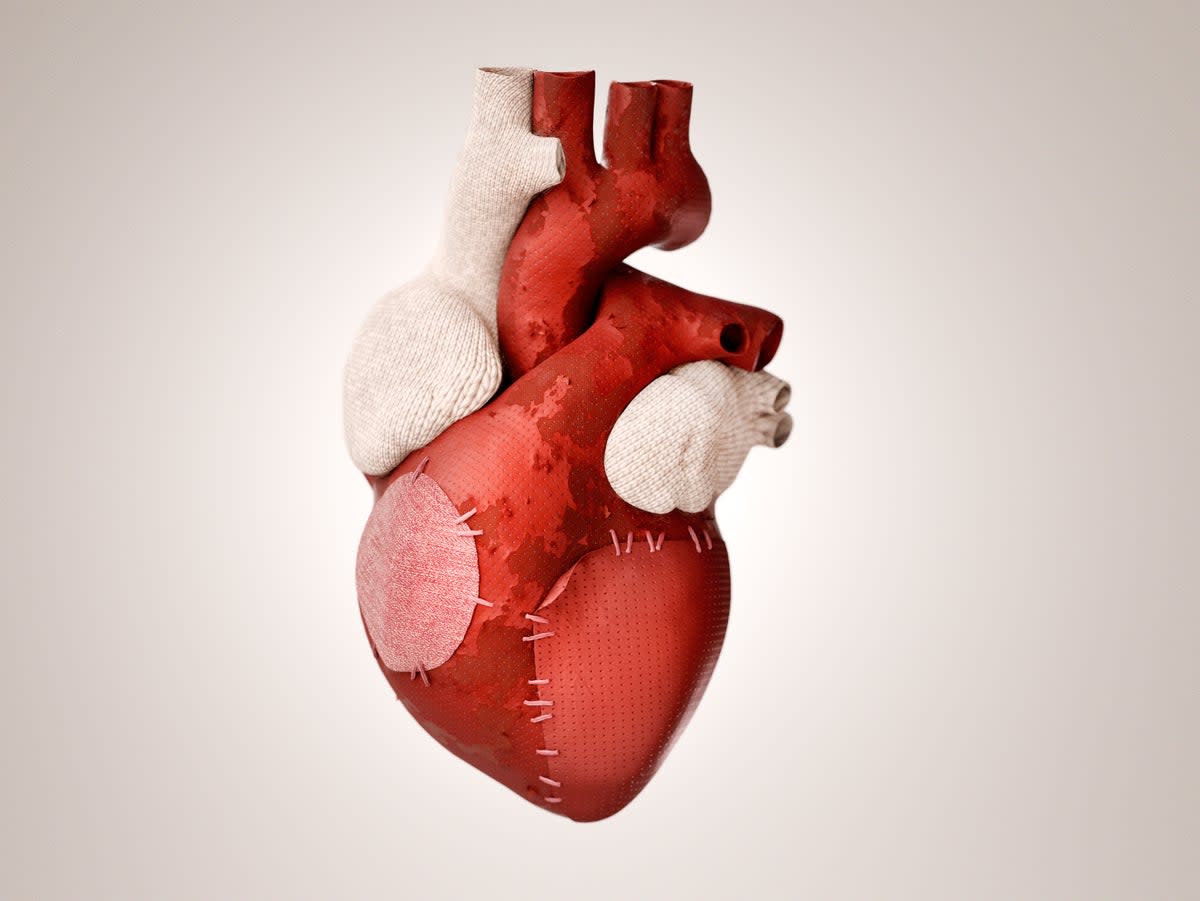

Researchers found that oxytocin can stimulate stem cells from the heart’s outer layer (epicardium) to move into the middle later (myocardium).

The stem cells then develop into cardiomyocytes, which are muscle cells that generate heart contractions. After a heart attack, these muscle cells die off and aren’t able to replenish themselves due to their highly specialised nature.

The study, published in the Frontiers in Cell and Development Biology journal, suggests that oxytocin “could one day be used to promote the regeneration of the human heart after a heart attack”.

After a heart attack, the muscle cells die off and aren’t able to replenish themselves due to their highly specialised nature.

In order to make their discovery, researchers examined heart repair mechanisms in zebrafish, which are able to regrow their heart even after as much of a quarter of it has been lost due to predator attacks.

They wanted to find out how zebrafish are able to repair the heart so efficiently. Previous studies have shown that a subset of cells in the outer layer of the heart can be “reprogrammed” to become stem-like cells called Epicardium-derived Progenitor Cells (EpiPCs).

EpiPCs can regenerate muscle cells and other types of heart cells, but are inefficient for heart regeneration in humans “under natural conditions”, the authors said.

However, they found that, in zebrafish, a boost of oxytocin can help trigger local cells to “expand and develop into EpiPCs”, which then migrate to the middle later of the heart to develop into muscle cells, blood vessels and other heart cells.

The study found that oxytocin has a similar effect on human tissue in vitro, helping to stimulate cells to become EpiPCs at “up to twice the basal rate”.

Meanwhile, a reduction of oxytocin prevented the development of EpiPCs in culture.

Dr Aitor Aguirre, the study’s senior author and assistant professor at the Department of Biomedical Engineering of Michigan State University, said: “Oxytocin is widely used in the clinic for other reasons, so repurposing for patients after heart damage is not a long stretch of the imagination.

“Even if heart regeneration is only partial, the benefits for patients could be enormous.”

He added that further research is needed to examine how oxytocin could help humans after a cardiac injury.

“Oxytocin itself is short-lived in the circulation, so its effects in humans might be hindered in that,” he admitted. However, “drugs specifically designed with a longer half-life or more potency might be useful in this setting.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News