LSD, Christine Keeler and a giant Wall of Sound: inside the Grateful Dead’s lawless early years

In the autumn of 1972, the Grateful Dead discovered a means by which they could extract $300,000 from the United States government with which to launch their own record company. The only requirement for receiving this seed money lay in persuading the administrators of the Minority Enterprise Small Business Investment Company [MESBIC] scheme that the group’s personnel were members of a minority. With this, at a stroke, the “hippies” were designated a special interest group.

But there was conflict. While some in the Dead’s sprawling organisation – a quarrelsome ecosystem in which the opinions of roadies and girlfriends carried as much weight as those of guitarists and drummers – loved the idea of the government giving money to a group that had been busted for drugs in both San Francisco (their de facto hometown) and New Orleans, others were appalled by the thought of clambering into bed with “The Man”. After much discussion, the plan was rejected. Instead, Grateful Dead Records was funded by leasing the band’s foreign rights to the distribution cartel WEA.

Straight away, there were problems. Despite being pressed on premium quality “virgin vinyl”, the label’s maiden LP, the Grateful Dead’s Wake Of The Flood – which has been reissued as a lavishly expanded 50th anniversary edition – was at once undercut by inferior bootlegs flooding the market from the other side of the United States. After the band decided that for once they wouldn’t half mind the government poking its nose into their affairs, the FBI declared the guilty party to be mobsters operating out of the Garden State in New Jersey.

“The shock to us was that no sooner had we gone independent than we became highly vulnerable,” recalled Steve Brown, one of the group’s numerous managers. “We didn’t have the kind of protection that big record companies have – armies of lawyers who you just don’t f___ with. We were, unfortunately, little and very f___-withable.” Then again, “I also think the bootleggers realised that we had a pretty limited market and that they weren’t going to be reaping the rewards of an Abbey Road [by The Beatles] with Wake Of The Flood”.

But still. Formed in Palo Alto in the mid-1960s, by 1973 the Grateful Dead’s unique position as a band whose success appeared both accidental and topsy-turvey was set in stone. On the one hand, by the metric of the US charts, this was a middle-ranking act with a respectable if far from blockbusting line of credit. They didn’t have hit singles – or at least not until 1987’s MTV-endorsed Touch Of Grey, they didn’t – while the material on their studio albums was, if not quite patchy, certainly not definitive.

On the other hand, however, they were a monster of the concert business. Onstage, they were definitive. In the same year that Wake Of The Flood grazed the US top-20, the Grateful Dead played to more than 100,000 people over two nights at the RFK Stadium in Washington DC. The following month, on July 28, a headline appearance at the Summer Jam saw an audience of more than six times that number descend on the small New York state town of Watkins Glen. Such was the influx, in fact, that even the sound-check became worthy of note.

“By Thursday night, there were already 80,000 to a 100,000 camped outside,” recalled the San Franciscan impresario Bill Graham, who built the stage at Watkins Glen. “I said to the promoters, ‘Let’s open at dawn and do a sound-check in front of a 100,000 people’. Everybody agreed… So they came in [on] Friday. At noon on Friday the sound was set. The Dead played for two-hours.” Support acts the Allman Brothers Band and The Band also performed lengthy sound-check sets. “It drove the kids crazy,” Graham said. “They’d gotten a taste – an appetiser – and they knew their heroes were there.”

It’s fascinating to consider exactly what this vast constituency thought it had gathered to see. In 1973, the Grateful Dead’s audience had yet to amass its vast library of bootleg cassettes recorded at concerts at which ticketholders arriving with tape machines and microphones were deposited in a designated “tapers’ section”.

Certainly, there weren’t 134-official live albums, either, as can today be found on Apple Music. Despite the vast numbers drawn to the band’s flame, it would be years before hard-core “Deadheads” conferred on internet message boards about legendary concerts at the Pittsburgh Civic Arena, in 1989, or Barton Hall, at Cornell University, in Ithaca, in 1977.

Even their recorded output didn’t really offer much of a clue that one was listening to America’s most adventurous band. In the studio, the Grateful Dead were merely laying down blueprints for material that would be built fully out on the road. In the space of 12-months, to take just one example, the song Dark Star grew from a two-minute and 44-second single to a monster that occupied an entire side of the 1969 double-live album Live/Dead. It kept growing, too. By December 1973, an audience at the Cleveland Public Auditorium enjoyed – endured? – the song on its largest ever canvas. It went on for 43 minutes, longer than Beethoven’s Sixth.

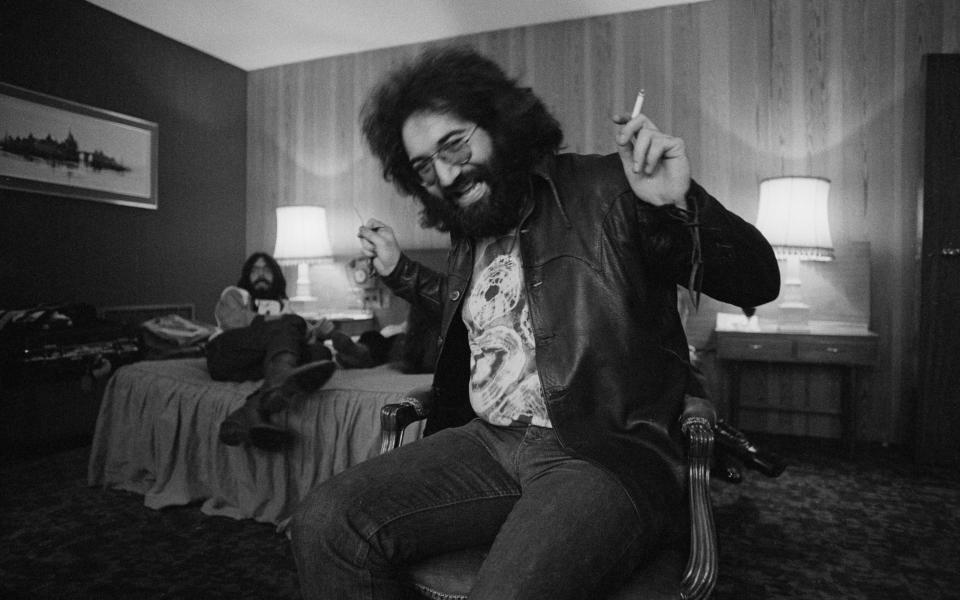

“[Dark Star] was incredibly different every night, and sometimes it was so utterly unrecognisable,” said Jerry Garcia, the Dead’s vocalist and lead guitarist. “[It] had no form, no real substance. The only thing it had was a snatch of melody and a few words. Everything else was open. It was meant to never be the same way twice.” Rhythm guitarist and vocalist Bob Weir admitted that “sometimes we know what we’re doing [and] sometimes we’re completely lost in what we’re doing… It’s a tenuous art, trying to make form out of chaos.”

It’s a wonder to behold that a band this weird could become, and remain, so popular. Conversely, they were either entirely overlooked, or else wholly misrepresented, by the uncommitted. Just this week, I saw a meme that claimed “the Grateful Dead are just country music for people who like LSD”. Maybe. But they’re also psychedelic rockers, an improvisational jam-band, heritage bluesmen, hippies who know how to play reggae, folk singers with a fondness for bluegrass, and, sometimes, just plain old rock and rollers. There was even a time when they were known as the “Disco Dead”, a period in the late 1970s that coincided with a collective fondness for cocaine. I mean, who knew?

Despite an enduringly fluffy image – “The Good Old Grateful Dead,” they called them – at times these were dangerous people, not least to themselves. Original singer Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, the one member who didn’t take illegal drugs, drank himself to death in 1973, at age 27. Over the course of a 30-year career, three keyboard players also died prematurely as a result of either alcoholism, drug misuse, or suicide (a fourth died at age 32 in a car accident). Reluctant bandleader Garcia was a chain-smoking virtuoso whose abilities were in time impaired not only by heroin and cocaine, but also by diabetes brought on by a diet of junk food and ice cream. His death from a heart attack in 1995, while in rehab at age 53, spelled death for the Dead.

They could also be uncommonly generous and loyal. Despite joining the band in the 1990s, fifth and final keyboardist Vince Welneck’s wage of a thousand dollars a day, every day, was the same as that paid to Garcia and other original members. They shared their drugs, too, albeit sometimes with those who might not have wanted them. According to drummer Bill Kreutzmann, the people “dosed” with LSD without their consent included a crew from the BBC who were rendered too high to film the Dead’s first ever performance on British soil, in 1970.

Two years later, in an exchange for the promise of a triple-live album, the band convinced Warner Bros (their record label at the time) to pony up half a million dollars for a two-month European tour that saw a party of almost 50-people head east from the Bay of San Francisco. During their time overseas, performing live earned them $3,000 per gig. As the caravan moved from the UK to the mainland, drugs were secreted inside amplifiers and other pieces of equipment. As the group’s management put it, in an exquisitely worded letter to continental promoters, “From a European perspective, the reality of the Dead may at times seem somewhat suspect.”

You reckon? “I was so stoned during one of the Paris shows that at one point I found myself under [the] piano,” recalled backing vocalist Donna Jean Godchaux in the book This Is All A Dream We Dreamed. “And I remember thinking, ‘Wow, this is really fantastic music, this Grateful Dead!’ Then, ‘Oh my gosh, I sing with this band!’ I don’t know how in the world we pressed through.” Following the first of two concerts at the Wembley Empire Pool (Wembley Arena in new money), Bill Kreutzmann spent the night with Christine Keeler, whose role in the Profumo affair nine-years earlier had rocked the establishment to a degree a hippy from California could only dream of. This being the area of free love, or at least cheap lust, he left his partner back at the band’s hotel.

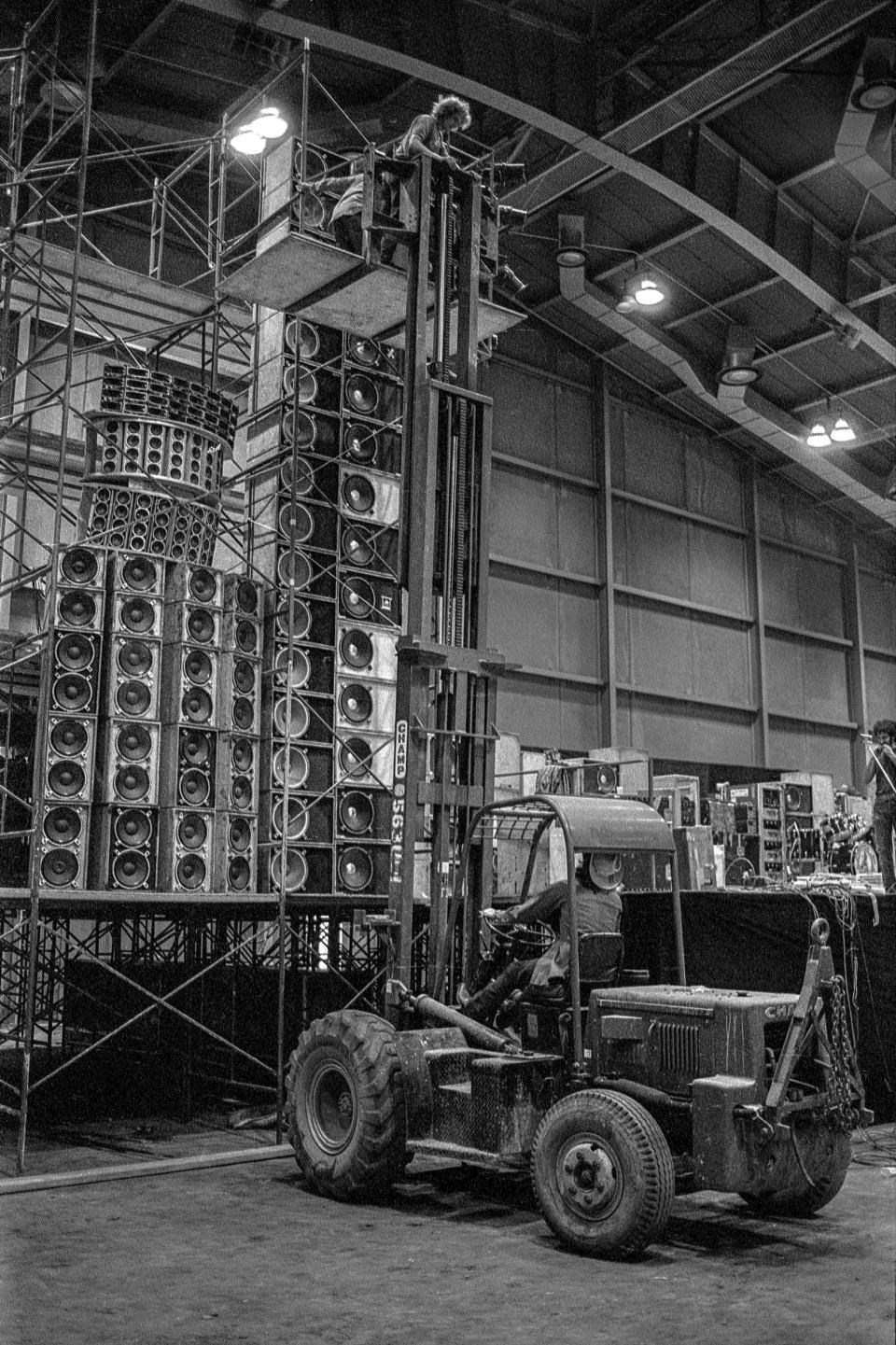

The Grateful Dead’s somewhat low-profile in Europe allowed them to appear in concert halls designed specifically for music. Back in the US, however, the problem of how to project sound 350-feet to the back rows of an arena built for basketball and ice hockey remained. Luckily for them, the summer of ’72 saw the return to the fold of cohort Oswald Stanley – fresh from a stretch in prison for making and distributing LSD – whose obsession with acoustics and amplification would, over the course of more than 18-months, help realise their grandest project to date.

Comprising 604 speakers and 305 amplifiers, the “Wall of Sound” was capable of launching the band’s music a quarter of a mile without any deterioration in either sound-quality or volume. The only problems were logistical. Costing a colossal $350,000, the rig took so long to set up and break down that the Dead needed two of everything in order that these walls of sound could leapfrog each other on tour. The hiring of a crew the size of a small army to keep the show on the road imperilled the sense of countercultural intimacy to which the group had always aspired.

As Garcia told Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner, in 1974, “As long as you can remember everybody’s name, you can [function]. But once you start not remembering, you gotta stop.”

With the band losing track not only of names, but of their own identity, stop they did. Printed on the tickets for the final performance of a five-night stand at the Winterland Ballroom, in San Francisco in October 1974, were the words “The Last One”. While camera crews shot footage for what would become The Grateful Dead Movie, backstage the normally hyper-vigilant Bill Graham, their West Coast promoter, was “dosed” for the first and only time after helping himself to an unopened can of 7-Up into which LSD had been injected through the needle of a syringe.

“That was the last night, as far as we were all concerned,” Bob Weir said of a retirement from the road that in truth lasted only until 1976. “We had pretty much roped ourselves into an unworkable situation. We had this huge PA we were carting around, we had a crew of, God knows, about 40-people, and we had to work too hard and too much to support it all – to the point where every time we played somewhere we lost money, but we had to keep working just to pay everybody who was on salary… It was just millions and millions of dollars that went into that. It wasn’t any fun after a while.”

The expanded edition of Wake Of The Flood, by Grateful Dead, is available now through Rhino Entertainment

Yahoo News

Yahoo News