McConnell's legacy: Wielding majority power to reshape court

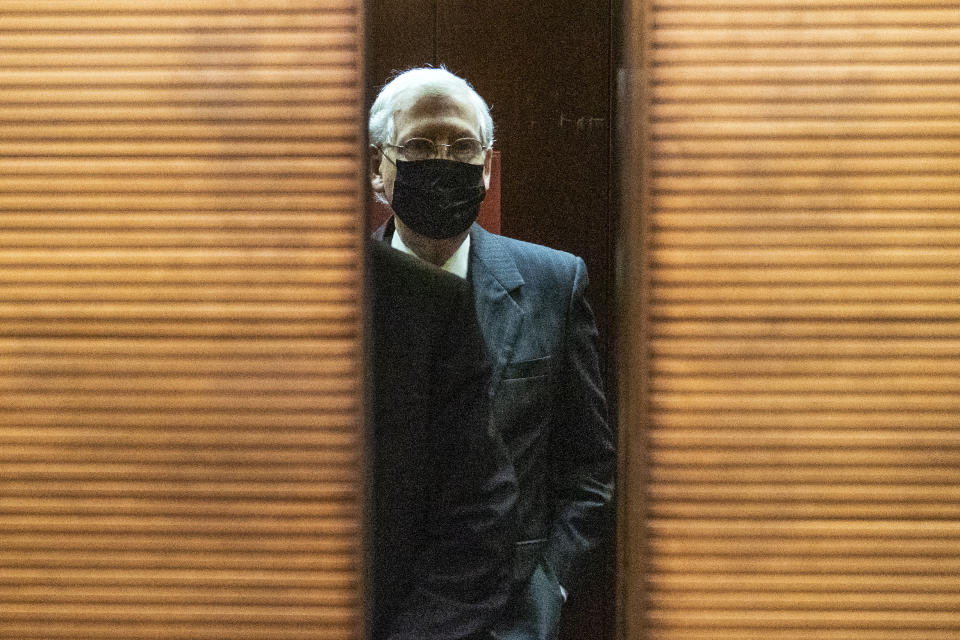

WASHINGTON (AP) — It’s legacy time for Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

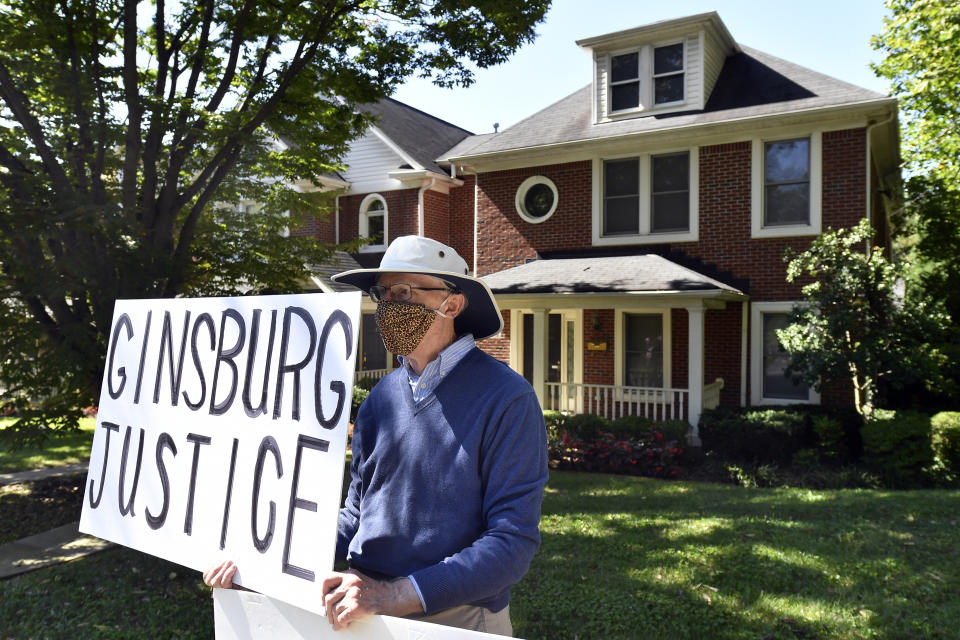

Fulfilling the Supreme Court seat left vacant by the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg before the fall election is as much about McConnell’s goal of securing a conservative majority on the court for decades to come as it is about confirming President Donald Trump’s upcoming nominee.

There’s no guarantee the Kentucky Republican will succeed. He is about to move ahead with a jarring and politically risky strategy to try to bend his majority in the Senate to accomplish the remarkable. If it works, he will have ushered three justices to the court in four years, a historic feat.

For better or worse, this will be how McConnell’s tenure as a Senate leader will be measured.

“Sen. McConnell already has played a huge role in shaping the Supreme Court for decades to come,” said Edwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California, Berkley School of Law. “A third confirmation, especially under these circumstances, would truly make this the McConnell Court for a long time to come.”

The path for how, exactly, McConnell will make this happen is being set swiftly in Washington. Many expect Trump to name his nominee in a matter of days and the Senate to start the confirmation process — condensing a typically monthslong endeavor into a matter of weeks.

Voting in the Senate could happen before the election or it could spill into the lame-duck period after the Nov. 3 vote. Either strategy is a political calculation for McConnell more than a substantive one.

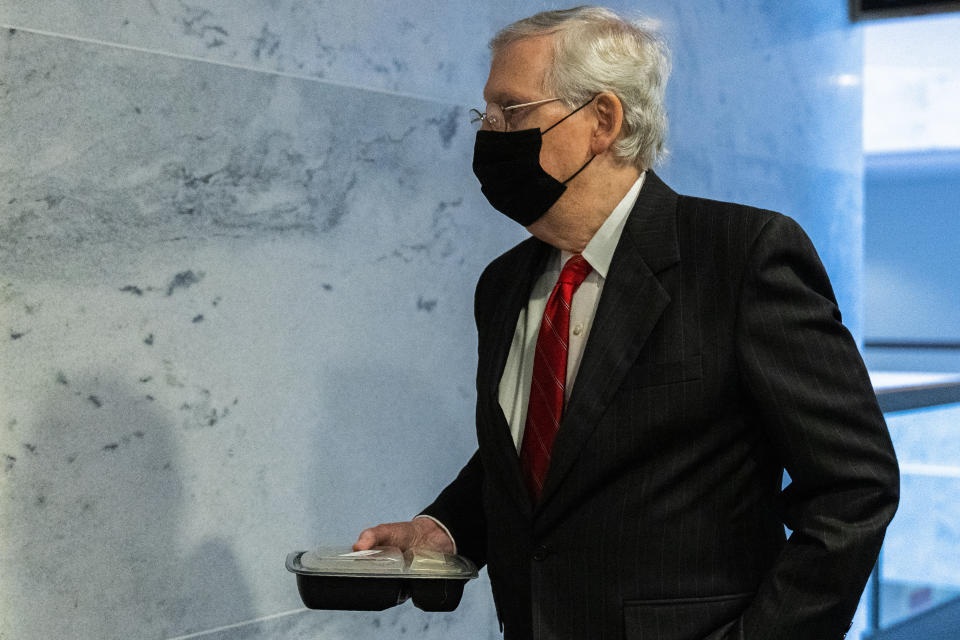

For the longest serving Republican Senate leader in history, the course ahead depends on what is best for the handful of GOP senators who face difficult reelections in November and could make or break McConnell's slim majority. Sen. Susan Collins in Maine wants no vote before the election. Others want swift confirmation.

Conservative voters are expected to be energized by the prospect of a right-leaning court, and McConnell must weigh whether the endangered senators risk alienating them if they shy from a confirmation vote. Or, in their swing states, would the senators like Cory Gardner up for reelection in Colorado fare worse if they rushed into a vote, upsetting centrist and independent voters who prefer to stick to Senate norms?

For now, McConnell is eager to push ahead, willing to leave behind those senators whose votes he can afford to lose. Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, signaled hours before Ginsburg's death that it's too close to the election to vote on a confirmation. She and Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, have been critical of Trump and could be votes against the nominee.

With a narrow 53-seat majority in the 100-member Senate, McConnell can lose three senators and still rely on Vice President Mike Pence to break a tie vote. Republicans think the risks of pushing ahead are worth it.

“McConnell's got to thread the needle here, and I have no doubt he will," said Mike Davis, a former chief counsel for the Senate Judiciary Committee. He now runs an outside advocacy group for conservative judges and advises Republican senators.

McConnell never set out to remake the Supreme Court as he has done during the Trump era.

But the death of Justice Antonin Scalia hours before one of the early-state presidential debates in February 2016 put McConnell on a course that will define his decades-long career.

McConnell stunned Washington by announcing the Senate would wait for the next president, after the November 2016 election, to choose Scalia’s replacement, blocking then-President Barack Obama’s choice of Judge Merrick Garland.

McConnell had no rule or precedent to fall back on, but he had a majority so he barreled ahead.

Once Trump became president, McConnell shocked Washington again by changing Senate rules to allow for simple confirmation, by 51 votes, rather than the 60 traditionally needed to advance a nominee. First the Senate confirmed Judge Neil Gorsuch in 2017. Then, with the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy, senators confirmed Judge Brett Kavanaugh in 2018 after dramatic hearings and allegations that the nominee had sexually assaulted women.

Now McConnell, again through an exercise in majority power, is saying that the standard he set in 2016 no longer applies because his party also controls the White House.

Hypocrisy, say Democrats. But McConnell is not likely be wounded as he rushes toward another confirmation.

Former Democratic Sen. Harry Reid of Nevada, the onetime majority leader who tangled fiercely with McConnell, was the first to change the Senate's voting threshold on lower-level nominees out of Obama-era frustration with GOP blockades. Reid warned Republican senators not to follow their leader down this path.

“If Republicans attempt to force yet another nominee onto the Supreme Court against the will of the American people, then they risk delegitimizing themselves and their party even more,” Reid said. He warned it would “further tear our country apart.”

But McConnell left no doubt where this was headed.

Absent a robust legislative agenda aligned with Trump, McConnell set out on the Senate’s other main role — confirmations. Along with the two Supreme Court justices, he has installed more than 200 federal appellate and trial court judges in the Trump era.

“Well, you don’t get to write your own legacy,” he said during an AP Newsmakers interview in 2018. "But I will say that what we’re doing in the area of the court, I think, is the most important thing we’re doing.

Asked in February by Fox News how he would approach a high court vacancy, now that it was again an election year, he showed no hesitancy.

“Yeah, we would fill it,” McConnell said.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News