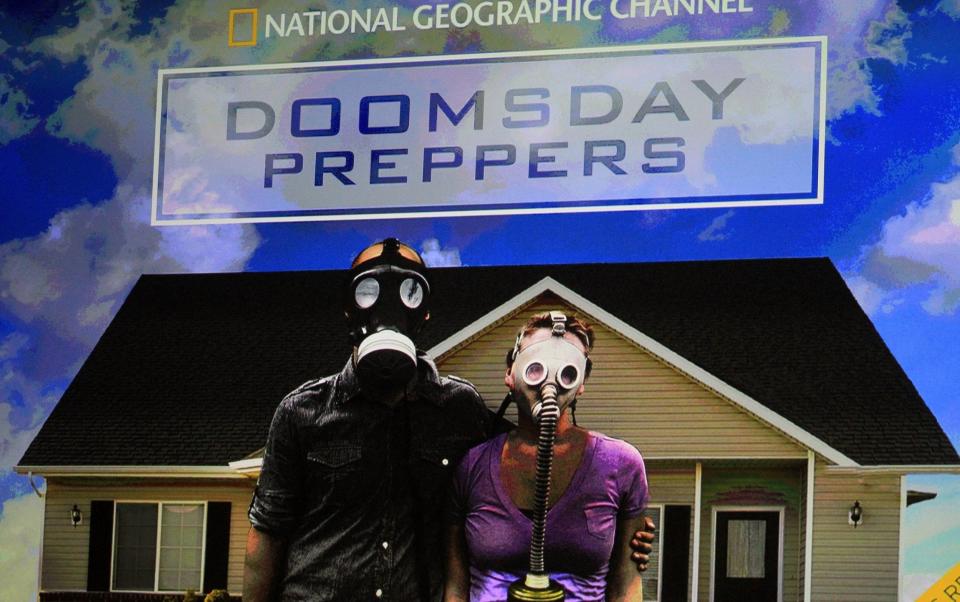

Meet the preppers – the ordinary folk getting ready for Armageddon

Prepping means thinking about things that can go wrong, says Dr Sarita Robinson, “and making sure you’re prepared for them. It could mean putting a fire extinguisher in the kitchen or having some spare loo rolls. Then at the other end of the continuum are the American survivalists, with a nuclear bunker and a weapons cache. The rest of us are somewhere in the middle.”

These are heady days for those who like to imagine the worst. ‘Preppers’ have been around since the advent of the atomic bomb. But now, between climate change, the pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, existential threats to our way of life have not loomed so large since the Cuban missile crisis.

There are plenty of reasons not to be cheerful: the threat of chemical, biological or nuclear war; extreme weather; natural disasters; disease, solar flares, meteor strikes. Every new bit of bad news vindicates the prepper mindset: pray for the best, by all means, but above all plan for the worst.

As deputy head of psychology and computer science at the University of Central Lancashire, Robinson studies prepping as part of her research, and is also a prepper herself. “I’m in the middle of the spectrum; I do realistic prepping,” she says. “I have a first aid kit, I count the seats to the exit on the plane, I have a ‘go bag’ – containing a change of clothes, water and food – and a survival bag, plus a little tiny stove so I can make a cup of tea.

“But I don’t know how to skin a rabbit or anything like that,” she adds.

Interestingly, Robinson’s research has found that preppers were better prepared psychologically to deal with the pandemic. “Those people who prepped, who were able to think of what might go wrong and predict what they might need in the future, did much better [during the pandemic]. They had lower levels of anxiety, depression and stress.

“Prepping is good for your mental health. You’re actively coping, putting something in place. One of the frustrations with the Ukraine invasion is that we’re all sat in the UK and feel like there’s no control. We’re watching it on the news and, as humans, we’re not really designed for that level of trauma.”

Of course, not everyone is a societal refusenik hiding in a concrete-reinforced Faraday cage hunched over a diesel generator. Moved by events in Ukraine, my wife came home the other day brandishing a solar-powered phone charger. If you bought an extra bag of pasta during the pandemic, that is a form of prepping.

But “if prepping interferes with your everyday life, you’ve got a problem,” warns Robinson.

Since the invasion of Ukraine, prepping shops around the country have experienced a surge in interest. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” says Justin Jones, sales director of the UK Prepping Shop, an emporium that stocks everything from crossbows to freeze-dried food and biohazard suits.

“Our overall sales have gone up 600 per cent. We used to sell two to three gas masks a week, but on the first day of the invasion we sold 60. They cleaned us out.” His customers used to be mostly male “Rambo-types”, he says, but “it’s probably 50/50 men and women now. Doctors, vets, policemen. Lots of ex-military.”

Robinson and Jones are unusual in being open about their own prepping. Mostly preppers meet online in forums on Reddit or Facebook or Discord, where they swap tips and tricks behind anonymous handles.

“The first rule of prepping is not to tell anybody,” says Dan, an engineer who lives with his wife and eight-year-old daughter near Birmingham. “I’m prepping for a family of three, not a family of three and all their friends. The most difficult part of prepping is thinking what you would do when everyone around you was thirsty and starving. A lot of our neighbours don’t have as much as a box of matches.”

Dan’s plan, in the event of disaster, is to hunker down at home and secure the house. “If we lock the doors and windows, we can survive for a month. Preppers often work on the rule of three: three minutes without air, three days without water, three weeks without food. I have gaffer tape and damp-proof membrane to seal the windows, a water tank, canned food, solar and petrol generators.”

In all, he reckons he has spent about £5,000 on prepping. “My wife doesn’t know the exact extent of it, but she’s very much on board,” he says.

For others, these kinds of provisions are out of reach. “I’m not prepping for the end of the world, because that’s too expensive,” says Damian, who lives in Bristol. Like Dan, he prefers not to give his surname. “Even if I had, it would be pretty boring just wandering around on my own. I don’t have a bunker. A lot of preppers talk about ‘bugging out’, where you take your fully stocked bag and head for the hills. But where am I going to bug out to? Somerset? In America it’s all about how big your knife is or how many guns you’ve got. But lots of that stuff doesn’t seem useful in the UK. If there’s a Russian invasion, you’re probably going to die; it doesn’t matter what you’ve got in your pantry.”

There is a key difference between American-style prepping and the British form, which recognises the limitations of US-style survivalism on a small, densely populated island where firearms are intensely restricted. Dr Michael Mills, a lecturer in criminology at the University of Kent who has studied prepping for over a decade, explains: “In the US, there’s a heavy Right-wing slant to prepper culture,” he says. “It coalesces around strident conservative and libertarian politics that are at least loosely associated with the Tea Party movement, Trump and that hard-right Republican movement. But in the UK it’s more diverse. There was a big uptick recently in prepping after Brexit, with a group called the 48 per cent preppers, named for the Remain vote, made up of more Left-liberal, Guardian-reading preppers.”

In Britain, he adds, the recent boom “is catalysed by certain upheavals which reveal the world to be an uncertain place: Brexit, Covid, toilet-roll shortages. Ukraine is interesting, because while war is ever-present around the world, people in Britain are able to look at Ukraine and think: ‘these people look like us’.

“But war also exposes the limits of prepping. If a shell hits your home, it won’t matter.”

Mills believes that prepping all over the world reflects a breakdown of trust in institutions. “There’s a sense now that anything could happen at any time,” he says. “Threats are more diffuse and nebulous, be it political upheaval, a terrorist attack or a natural disaster. And there has been a slow evolution of declining faith in political institutions. The sense that you’ll need to go it alone, when the protection of authorities and institutions has diminished.”

Even the best preparation, in other words, is no match for good governance. Looking at the upheaval around us, it’s hardly reassuring. Especially now gas masks have sold out.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News