Merriam-Webster editor on her new book - and why dictionaries matter

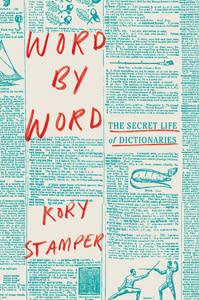

What is the hardest word to define? What’s the longest word in English? These are just some of the questions Merriam-Webster editor Kory Stamper has to field when she tells people about her job. It’s one of the reasons she was inspired to write her new book, Word By Word: The Secret Life of Dictionaries.

“I wanted to give people an idea of how the dictionary works because you do this long enough and it’s the same questions over and over again,” explains Stamper, who draws on her years of experience defining words to give viewers a glimpse into what goes into putting together a dictionary. “There are actually books about dictionaries on the market, but they’re mostly scholarly and really dry. That’s not my experience with this job.”

Inspired, Stamper details her experience not just at the publisher, but also with the changing nature of the English language and the way we use it. EW spoke to Stamper about life at Merriam-Webster, why dictionaries matter, and why people get angry when definitions change.

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY: What was the inspiration for the book? Did you want to give people a behind-the-scenes look at the life of a dictionary editor?

KORY STAMPER: The book really solidified when I started thinking, “Why do dictionaries matter? What’s the point of dictionaries in the Google age?” I was thinking about the type of expertise that goes into writing dictionaries and then the type of things you learn about English as you write one. I know all this bizarro stuff about the English language that has made me fall in love with it in this new way because I think people who like words also get really frustrated with how illogical English is. For me, a dictionary is a living record of a living language, and they’re important because language is important to us. My hope is that people read this and love English more.

You share a surprising description of what it’s like working at the Merriam-Webster offices. The nondescript building where people communicate using color-coded cards is not what I pictured at all.

It’s not what anyone pictures. When I went in for my interview, I drove by the building like five times, and this is before the era of Google maps, because I was like, “That’s where this should be, this place should be, but that can’t be it. That little building, that can’t be it. I must be on the wrong street.” That is not the building that you think of when you think of a dictionary.

In a lot of ways, it’s mirroring what’s happening now, especially in terms of the Twitter account, where you wouldn’t expect the dictionary to have this kind of attitude.

The fun thing for me about hearing people respond, especially to that - the description of the building and the people who work there - is that it is the same thing that’s happening with the Merriam-Webster Twitter account. It’s the first time that people have ever realized that there are people behind the dictionary, that it’s not just a computer algorithm that combs the Internet and spits out a definition. Those people and those places have personality, and they have their own loves and desires and hates and everything that the person who’s reading the book, or reading the Twitter account, has. The only difference is that they have this weird job where they write dictionaries.

Has that changed the way people react now when you tell them you’re an editor for Merriam-Webster?

Yeah. The first thing that people say is, “Oh my god. Are you the one who does the Merriam-Webster Twitter account? It’s amazing.” Then I have to disappoint them and say, “No, I don’t. There’s a woman in the New York office named Lauren who does the Twitter account.” People definitely are like, “Ooh.” The Twitter account has definitely made people realize the dictionary is human, so now people are really interested in the humans behind the dictionary.

What are some of the more interesting or unusual sources you have to read to figure out how language is being used currently?

My colleague, Emily Brewster, was responsible for writing the definition for twerk, so she spent a long time on YouTube, watching people twerk. This is the sort of thing that lexicographers do in the face of that sort of thing. I think she watched, possibly, 100 videos of people twerking to figure out what the essential motion behind a twerk was. Is it a twerk? Is it twerking? So YouTube is one. I’ve seen all sorts of stuff that ends up in the database, and that’s always funny. The best one was I saw was a while ago. Someone had marked the Yellow Pages for interesting information. I have marked beer bottles for things like “mouthfeel.” You see that word in Food & Wine and in Gourmet and in Bon Appetit, but here’s a beer manufacturer using the word. That means it’s moving outside the pages of food. It’s still alcohol, but people are picking it up; that means it’s [usage] broadening. I saw someone bring in empty and washed-out cans of cat food that they had found. If you write dictionaries, you can’t stop reading.

One of the things you mention in the book is when people got really mad about the definition of marriage. What is it about stuff like that that makes people so angry?

The big thing with “marriage,” and there are other words that are like that, it’s a really good clear example for people. The word describes a thing, and people assume that when you change or adapt the meaning of a word, that you’re changing the thing, and particularly in our current cultural moment, the ways that people use words have ended up becoming markers of where they fall on a social or political spectrum.

It is funny to me that we were the last major dictionary to make a change to the entry, but because we’re also a prominent dictionary, we’re the ones who really got slammed with complaints about it, and the complaints were not about the entry or the word. It was about how we are sanctioning the thing, and it’s because language is so personal to us. We internalize language so much because that’s one of our primary forms of communicating to people. When you change the definition of a word, that represents a core value to somebody, then they feel like you are challenging that value, even if you’re not.

So you’re really just reacting to the way the usage of the word has changed.

Absolutely. People think of the dictionary as this broad authority, so if they find a word or meaning in the dictionary, they feel like they’re sanctioned to use it that way. And if they don’t find it in the dictionary, then they think that the word or meaning, or sometimes the thing, doesn’t exist. The heartbreaking flip side of this is when you get a lot of people who will ask you to remove slurs from the dictionary because then hatred will no longer exist. You have to go, “A) That is not how language or dictionaries work. B) That’s not how humanity works. If it were as simple as just taking the word “genocide” out of the dictionary to get rid of it, don’t you think we would’ve done that at this point? Words are a cultural marker. And the dictionary follows the culture.

You’ve been doing this for 20 years now; is there something that really stands out to you over your time at Merriam-Webster in terms of defining or editing a word?

A lot of people ask, “How long does it take to feel like you know what you’re doing?” Because it’s such a complicated process, and I think most of us would agree, it just takes years. The learning curve on this job is crazy long. We began work on a dictionary for adults who are learning English as a foreign language, and it was the first dictionary in company history that had to be written entirely from scratch. You couldn’t take another dictionary and use its word list or its definitions as a basis for this because defining for people who don’t speak English is wildly different than defining for people who do. Even if you’re defining for teens, they’re native English speakers, and so you can use what we call defining vocabulary, the types of words that you use to write definitions. When you’re writing for people who are just learning English, that defining vocabulary has to be tiny. How do you explain the word “idea”? How do you explain what the verb “do” means when you can’t use words that are more complicated than “do” or “idea”? You would have to come up with these new ways, new conversational ways of talking. When you say, “Let’s do dinner” what you mean is you would like to eat dinner with that person and that doing dinner is different from doing your laundry. You say, “Let’s do laundry.” That’s not idiomatic.

To a learner, you have to explain why that’s different, and you have to do it in really simple English, so I copy-edited each of those, and by the time I finished, I remember very clearly finishing “do” and signing the batch back in, and I went home that night and I was like, “I’m a lexicographer now. I can do this. I know how to do this.” It was like my world had just shifted five degrees to the right. I still write clunker definitions, don’t get me wrong. No one ever gets it totally right, but it just felt like there was just this small click, that was like, “Oh, that’s what I do. This is who I am. This is what I do.” That probably happened eight years into my tenure as a lexicographer.

Word By Word is currently available for purchase. Order it here.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News