Miami boy's overdose death shows a powerful opioid's chilling potential

Thomson Reuters

MIAMI (AP) — A 10-year-old boy from a drug-ridden Miami neighborhood apparently died of a fentanyl overdose last month, becoming one of Florida's littlest victims of the opioid crisis, authorities say. But how he came into contact with the powerful painkiller is a mystery.

Fifth-grader Alton Banks died June 23 after a visit to the pool in the city's Overtown section.

He began vomiting at home, was found unconscious that evening and was pronounced dead at a hospital. Preliminary toxicology tests showed he had fentanyl in his system, authorities said.

"We don't believe he got it at his home," Miami-Dade State Attorney Katherine Fernandez Rundle said Tuesday. "It could be as simple as touching it. It could have been a towel at the pool."

She added: "We just don't know."

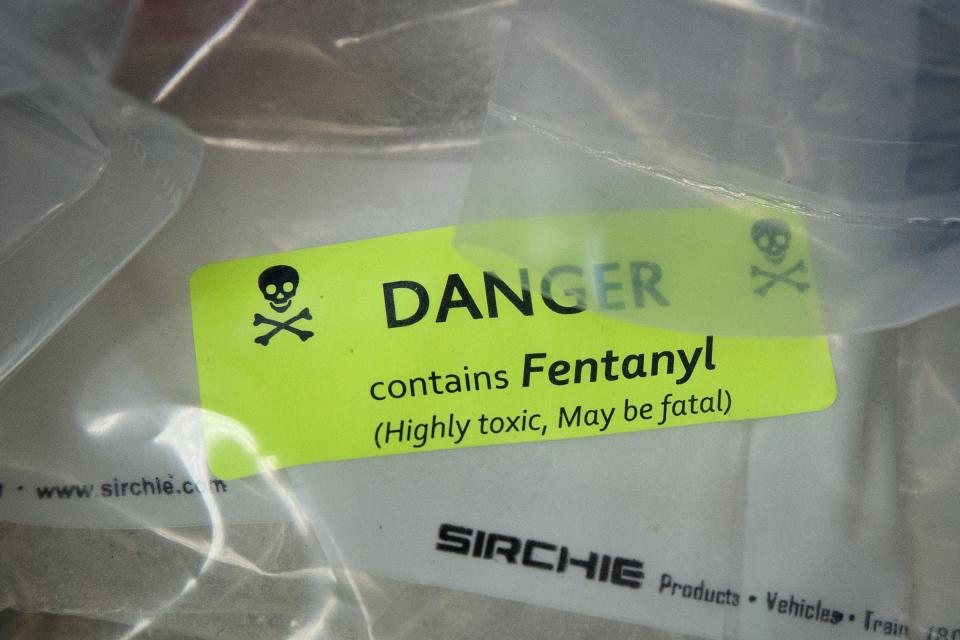

The case has underscored how frighteningly prevalent fentanyl has become — and how potent it is. Exposure to just tiny amounts can be devastating.

Investigators said Alton may have been exposed to the drug on his walk home in Overtown, a poor, high-crime neighborhood where Assistant Miami Fire Chief Pete Gomez said he has seen a spike in overdoses in the past year and where needles sometimes litter the streets.

"There is an epidemic," Gomez said. "Overtown seems to have the highest percentage of where these incidents are occurring."

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

The three-block walk between the pool and Alton's home took him down streets that appeared relatively clean Tuesday, but on the block in the other direction from his home, trash littered the pavement and empty lots. Homeless people slept in the shade of an Interstate 95 overpass.

Detectives are still trying to piece together the boy's final day. Rundle appealed to the public for information.

"This is of such great importance. We need to solve this case," she said. "I believe this may be the youngest victim of this scourge in our community."

The boy's mother, Shantell Banks, was informed of the preliminary findings last week. A distraught Banks told The Miami Herald that her son was a "fun kid" who wanted to become an engineer and loved the NFL's Carolina Panthers, especially Cam Newton.

Jessie Davis, who lives in an apartment house next to the building where Alton lived, said her grandchildren, ages 8, 9 and 10, regularly make the same walk to the nearby park with a swimming pool. She said she initially thought the pool water made Alton sick and was shocked by news reports that he had been exposed to fentanyl.

"Where would a 10-year-old baby get something like that?" Davis said.

Thinking about her own grandchildren going to the pool, Davis said, "I'm going to tell them, 'Don't touch nothing.' I don't know whether they think it's candy, but somebody needs to tell these kids something."

The Florida Department of Children and Families said it is conducting its own investigation, in addition to that of the police.

Tommy Farmer/Tennessee Bureau of Investigation via AP

Fentanyl is a synthetic painkiller that has been used for decades to treat cancer patients and others in severe pain. But recently it has been front-and-center in the U.S. opioid abuse crisis.

Perhaps best known as the drug that killed pop star Prince, it is many times stronger than heroin. Dealers often mix it with heroin, a combination that has often proved lethal.

Fentanyl is so powerful that some police departments have warned officers not to even touch it. Last year, three police dogs in Broward County got sick after sniffing the drug during a federal raid, officials said.

Gomez said his crews wear long sleeves, coveralls, gloves and masks while handling fentanyl. And "you never want to start reaching into people's pockets," he said, explaining that crews often cut people's pockets open for fear of pricking themselves with needles.

The Florida Legislature addressed the epidemic, passing a law that imposes stiff mandatory sentences on dealers caught with 4 grams (0.14 ounces) or more of fentanyl or its variants. The law also makes it possible to charge dealers with murder if they provide a fatal dose of fentanyl or drugs mixed with fentanyl. The law goes into effect Oct. 1.

Nearly 300 overdose deaths in Miami-Dade County last year involved variants of fentanyl, according to the medical examiner's office. Statewide, fentanyl and its variants killed 853 people in the first half of 2016. Of those, only nine were younger than 18.

NOW WATCH: Public policy expert: Trump's claim that drugs are cheaper than candy bars isn't 'entirely untrue'

See Also:

Yahoo News

Yahoo News