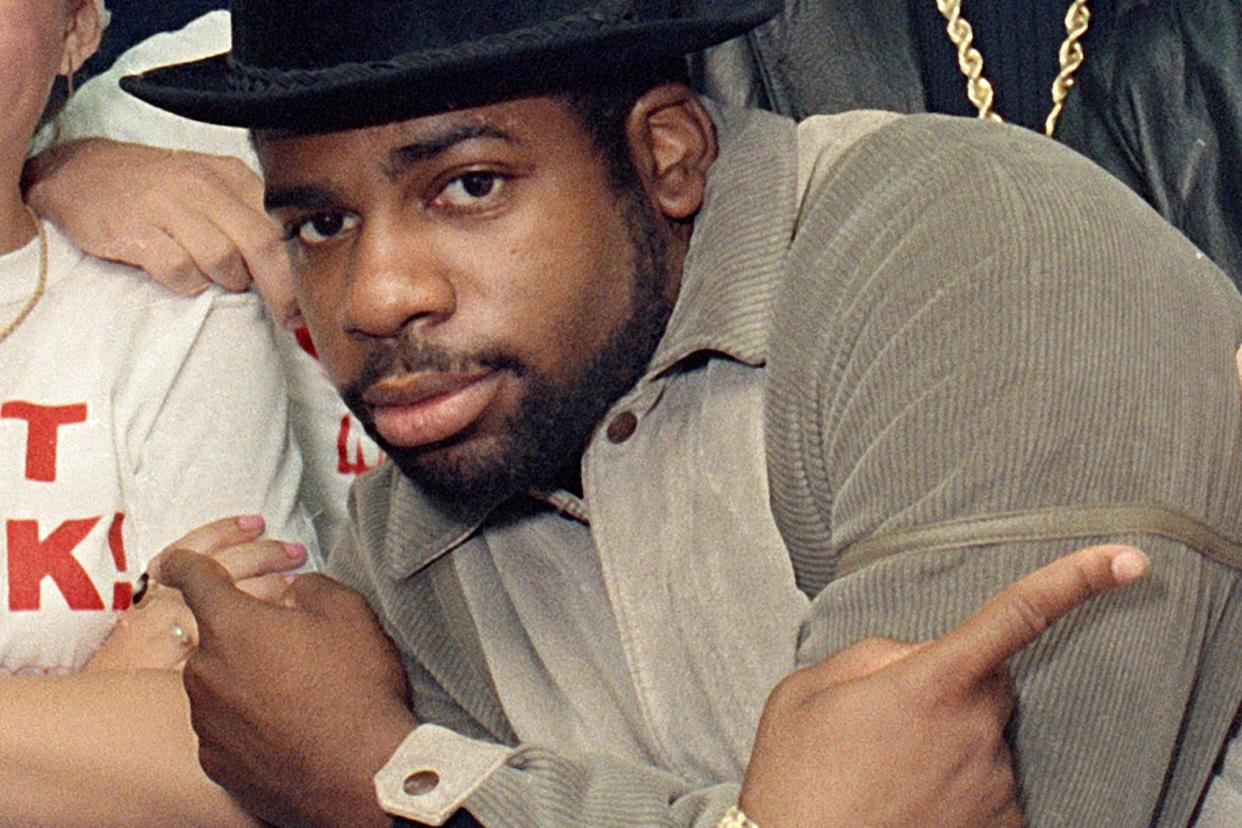

Will murder trial finally solve mystery of Run-DMC’s Jam Master Jay?

Who killed Jam Master Jay has been one of rap’s most enduring mysteries. But this week a Brooklyn court heard from a witness who was in the New York recording studio when the Run-DMC hip-hop pioneer – born Jason Mizell – was gunned down in 2002.

Across the courtroom, studio gofer Uriel “Tony” Rincon dramatically pointed to the rap star’s godson Karl Jordan Jr, also known as Little D, and told jurors: “He kind of walked directly to Jay and gave, like, half a handshake, with an arm. And at the same time, that’s when I hear a couple of shots.”

Related: Run-DMC’s Jam Master Jay remembered, 10 years on

Rincon, who had been employed as a studio assistant, said he’d been sitting in the studio’s lounge area, playing a football video game and talking business, when the door opened. One of the shots struck Rincon in the leg. “And then I see Jay just fall.” An autopsy later determined Jam Master Jay, 37, had been killed by a single bullet to the head.

Jordan, 40, and accused accomplice Ronald Washington, a childhood friend of the DJ and known as “Tinard”, have both pleaded not guilty to murder while engaged in a narcotics trafficking conspiracy.

The trial could also shed light on why other notorious rap murders, including those of Tupac Shakur in Las Vegas in 1997, and Biggie Smalls, AKA the Notorious BIG, in Los Angeles a year later, have yet to be conclusively resolved through the criminal justice system.

For 15 years, Rincon told authorities he did not recognize the gunman who he saw kill Mizell. On Wednesday, he was asked repeatedly why he had maintained that – to NYPD investigators, the FBI, and in interviews – only to come forward in 2017.

“I was scared, and I couldn’t believe what I saw,” he told the court.

Run-DMC, formed in 1983 by Joseph “DJ Run” Simmons, Darryl “DMC” McDaniels and Mizell, altered the aesthetic of hip-hop music, elevating the DJ to the level of the MC. They notched the now half-century-old genre’s first gold and platinum albums.

Along the way, the collective’s hits included King of Rock and It’s Tricky, and a cover of Aerosmith’s Walk This Way established that hip-hop beats could be put to rock. The song hit No 4 on the US charts and remains the pre-eminent crossover hit of the 1980s.

Mizell cultivated an anti-drugs image – something that is now being challenged in court. Prosecutors allege Mizell was murdered because he cut Jordan and Washington out of a 10kg cocaine transaction he had received from the midwest. That set in motion, prosecutors say, a conspiracy to kill Mizell. If convicted, Washington and Jordan face at least 20 years in prison.

Over the years, various theories around Mizell’s murder have been advanced. In 2003, the convicted drug dealer and Murder Inc Records associate Kenneth McGriff was floated as a possible suspect because Mizell had flouted a blacklist of 50 Cent, a Mizell protege, after 50 had rapped about McGriff’s dealings.

But that same year, a Playboy article uncovered evidence that Mizell had turned to drug trafficking when his career stalled, debts piled up, and that the hit was allegedly ordered as retribution for late payment on the cocaine deal to a trafficker known as “Uncle”.

Four years later, Washington was identified as the armed accomplice of the man who shot Mizell, in court papers relating to a string of armed robberies that occurred just after the DJ was killed.

Charis Kubrin, a professor of criminology, law and society at the University of California, Irvine, said the case presents twin questions that hang over the high-profile murders of Mizell, Shakur and Smalls alongside broader questions of criminal justice: rappers being caught up in the criminal justice system, and police-community relations in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Judge Lashann DeArcy Hall has prevented prosecutors from introducing evidence that relies on genre-conventions or artistic expression into the Mizell case, noting in 2020 she was “not going to hold any individual accountable for the lyrics in a rap song that is consumed by our community – and, in fact, it’s consumed by me”.

But the second concept – of fear of retaliatory violence in communities underserved by police – has already emerged.

A study Kubrin conducted of 30 years of homicide data in St Louis found that retaliatory homicides in response to a perceived threat occurred almost exclusively in a handful of impoverished communities characterized by tense police relations and by informal responses as crime control: the very communities from which hip-hop emerged.

“The clearance rates of homicides in those communities were abysmally low, and part of that is because the community did not trust the police and the police were unable to get together with the public when they needed them most, to figure out who might be a suspect in a crime and speak to witnesses,” Kubrin said.

“You’d have homicides that occurred in front of 10 or 15 bystanders and no one would speak to the police,” Kubrin added. “Part of that was street code. You don’t report, you handle the problem on your own. The flip side of that was that people did not trust the police to protect them and there was a very real fear or retribution and retaliation.”

During his testimony, Rincon said he “omitted the truth” because he was scared for himself and his mother. It was not until 2017, 15 years after Mizell’s murder, that he decided to say what he saw that night.

“I felt that his wife and his children needed closure, and I felt that they should know what took place,” he testified.

Lawyers for Washington have argued that the government’s case is held together by “tape and glue”. Jordan’s attorneys have said he was at his then girlfriend’s home at the time of the shooting.

Under cross-examination, defense lawyers have repeatedly pointed to the inconsistencies in Rincon’s account, including a 2007 Daily News interview in which he acknowledged that Mizell was a marked man – he had kept a gun on a sofa armrest during the 10-to-15-second encounter.

Over the coming weeks, jurors will hear from other witnesses who are likely to place Jordan and Washington at the murder scene, as well as witness who, according to the government, will say that the pair confessed to the crime.

As Rincon’s testimony wound down last week, Jordan’s lawyer Mark DeMarco, asked the prosecution witness if he was still scared today.

“Of course,” Rincon said.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News