Mystery of Mexico’s cartel wars grows as ‘The Mouse’ is rescued

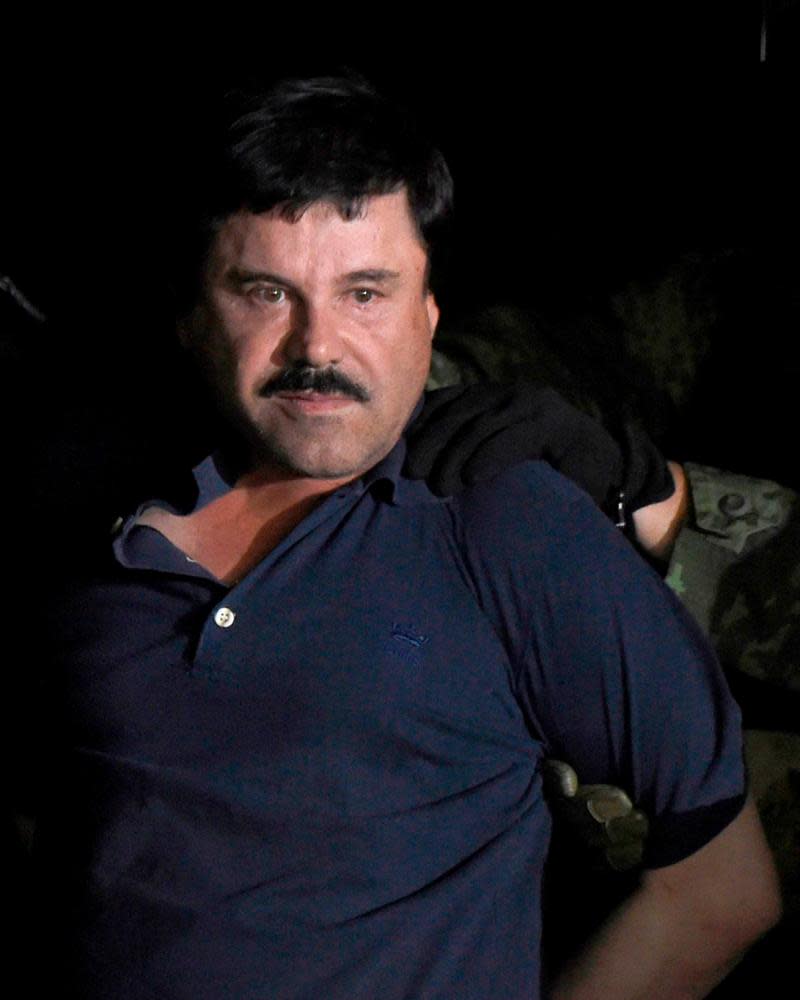

Sinaloa cartel gunmen took over a Mexican city on Thursday, turning the streets into an apparent war zone. Their mission was to rescue the son of the notorious drugs lord, El Chapo, who had been captured by police. Officers were forced to release Ovidio Guzmán López after gang members threw up roadblocks with blazing trucks, and staged a prison break of 51 of their comrades.

The battle came only a week after Mexico’s interior secretary Olga Sánchez Cordero pledged that the country would “very soon” see results of the deployment of a 70,000-strong National Guard – a showpiece unit formed this year by president Andrés Manuel López Obrador – against resurgent violence and record murder levels.

But on Monday, 14 police officers were killed by cartel gunmen in Michoacán. Fifteen more lives were lost next day during a firefight in Guerrero. In Thursday’s fighting, a soldier and civilian were killed in Culiacán, in Sinaloa state, and others wounded – with questions hanging over how it happened.

In reality, the new National Guard is deployed mostly against migrants in a joint policy with the US. While hundreds of guards blocked a convoy of Hondurans in Tuzantán last weekend, security minister Alfonso Durazo conceded on Friday he had deployed only 35 troops to seize Ovidio Guzmán López – “The Mouse”, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán’s fourth son by his second wife, Griselda López Pérez – blacklisted in the US in 2001 and charged last February with cocaine trafficking.

What’s going on? On the surface, Amlo – as the president is known – at last cracks down on a cartel long known for its conviviality with government, but is outgunned; unconfirmed reports indicated the detention on Tuesday of Ovidio’s mother.

But why mobilise a paltry crew of 35 against a mafia boss? How did such a cartel counter-force arrive to confront and humiliate it immediately? There’s choreography at play – but by whom, of what?

Even the story’s telling compounds its mystery. Durazo at first sought to have Mexicans believe that a routine patrol was fired upon from a house which, when raided, happened to be harbouring Ovidio Guzmán. (For El Chapo’s son to draw fire on himself beggars belief even by the standards of his own outrageous reputation.) Only later did Durazo concede to a news agency that Ovidio had been released.

The president then contradicted his own minister, confirming that the operation was “based on an arrest warrant for an alleged criminal”.

Two other factors further muddy the waters: one video clip shows troops and cartel gunners giving one another high-fives after the former were surrounded and neutralised. The prison break would hardly be the first time authorities have been directly or indirectly party to an escape, not least one by El Chapo – who founded the Sinaloa cartel and is now in jail in the US – himself.

The cartel has fragmented since Guzmán’s extradition and conviction. Factions compete for the succession: one led by the guiding but ailing hand of Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, suspected of delivering El Chapo to the US authorities, or at least withdrawing his official protection; another, loyal to Guzmán, is led by his sons, “Los Chapitos” – Iván Archivaldo Guzmán Salazar (son of El Chapo’s first wife Maria Alejandrina Salazar Hernández) and Ovidio.

A third interest, led by Dámaso López, “El Licenciado”, now captive in the US, defected to the rising Jalisco New Generation cartel, to which Sinaloa is losing initiative within Mexico.

Such an attack on the state is not El Mayo’s usual strategic style. It is more typical of Guzman’s sons, whose brazen tactics he abhors.

British film-maker Angus Macqueen – who penetrated further inside the Guzmán family than any foreign reporter, interviewing El Chapo’s mother – noted: “This is the first open confrontation between the authorities and the Sinaloa cartel. The remarkable thing is the speed with which hundreds of armed cartel members arrived and dominated the centre of this town.”

Anabel Hernández first described the state sanctioning of El Chapo’s escape from jail in 2001 and named the cartel’s connections at the apex of power in her book Narcoland; after numerous threats to her life, she has completed a new volume on the inner workings and reach of the Sinaloa cartel.

“What happened in Culiacán just doesn’t make sense,” she told the Observer. “No sense in the government sending 35 people to take Ovidio. That’s his girlfriend’s house, and they’d have followed him there with intelligence. There’s the municipal police and an army base in Culiacán; helicopters can arrive easily from [nearby] Mazatlán.”

And, she cautions: “Never forget that the Sinaloa cartel remains a vast organisation across 70% of the world. It’s far bigger than El Chapo, and after he was sentenced, the sons got a very small part; the huge share came under El Mayo. But the sons have money to spend, and that’s what happened in Culiacán: if you pay people to carry the weapons, you get what you want.”

Official collusion at some level is inevitable in Thursday’s battle-as-theatre. Hernández puts the events in perspective: “For a decade, war between the cartels is reflected within the police, army and all forces.

“One cartel is protected by some officers, another cartel by others. That has not changed – the prison break yesterday must have been sanctioned from within the authorities. All we can be sure of is that someone betrayed the government in Culiacán yesterday.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News